Winnemucca lies at about 4,200 feet above sea level, has a desert climate with about eight inches of precipitation a year, is the only incorporated city in Humboldt County, and has itself a population of only about 7,400 people; as a result, the air is clean and fresh. I felt groggy when I awoke — too many days of driving this week, and too many hours of dealing with Dad’s papers last week have taken their toll — but I got up to go get a cup of coffee, and as soon as I had taken a few breaths of that cool, clean desert air, before I had even had any caffeine, I felt alive and awake and ready to go.

I headed west on Interstate 80, then south on U.S. 95. Just after I had made the turn onto U.S. 95, a two-lane highway with a 70 mile an hour speed limit, I saw a little sign that read “California Trail / Auto Tour Route / Truckee Route,” and I could see a rough track running west through the desert. I found a place to turn around, and walked out along the track into the desert.

Maybe this track followed the route of the original California Trail turn-off to Truckee, the route the Donner Party followed to its cannibalistic end in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, but the tracks that were visible were those of twenty-first century off-road vehicles. The temperature was now up to about ninety degrees, but the air was still fresh and dry, and I walked briskly along for for a mile or so until my car was a speck in the distance. It must have rained yesterday, for the whitish soil was still damp, and my feet crunched pleasantly on a dry crust that had formed on top of the moist soil. Black, red, and buff-colored igneous rocks were scattered on the surface of the soil, many of them with air bubbles in the rock.

As I drove away from where I had parked, I saw that just south of where I had got out and walked, the highway crossed over a small ditch with open water in it. Perhaps this was why Truckee Route followed this particular path across the desert, following that dry wash that sometimes had water in it.

I stopped at Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge east of Fallon, Nevada, and it was just as I remembered it: a stunning oasis of open water and green wetlands. The difference this time was that Stillwater Reservoir had water in it; when I was here a couple of years ago, the reservoir had been dry. The open water, the green tule rushes and cattails, and the loud calls of a myriad of birds — squawking White-faced Ibis, grunting and hooting American Coots, booming American Bittern, quacking Blue-winged Teal and Cinnamon Teal, screaming Red-winged Blackbirds — contrasted bizarrely with the quiet of the reddish desert mountains in the distance and the serene blue sky overhead.

On my way through Fallon, I stopped at the bookstore in town, Third Space Books, and had a long talk with one of the owners, who turned out to be an early childhood educator who was worked with troubled adolescents during the summer. She was pursuing her doctorate of education online, and I asked about her online program and how she liked it. Aside from the obvious point that it obviously made more sense for her to get her degree online than driving an hour each way to study at the University of Nevada in Reno while holding down a full-time job in education, she also preferred online learning.

From Fallon, I drove up over the Sierra Nevadas towards home. As usual, I stopped at the Donner Pass rest area, and took the trail from the rest area towards the Pacific Crest Trail, where I ran into a long-haul trucker who was taking a break from driving. He said that while he had stopped at that rest area many times, it had always been at night, and this was the first time he had seen it during the daylight. “Where does that trail go?” he asked, and I said, “Pretty soon it meets another trail, and if you turn left you can walk to Canada, and if you turn right you can walk to Mexico.” His eyes widened, and he clearly thought I was putting him on, so I added, “I’m not making this up,” and explained to him about the Pacific Crest Trail. He said he’d like to return sometime with his thirteen year old son, who sometimes came with him on these trips. On the other hand, he also said that he didn’t like driving through Nevada because there were casinos and slot machines everywhere, and he had lost too much money gambling earlier in the day, and he was thinking of asking his boss to only send him along the southern route, via Interstate 40.

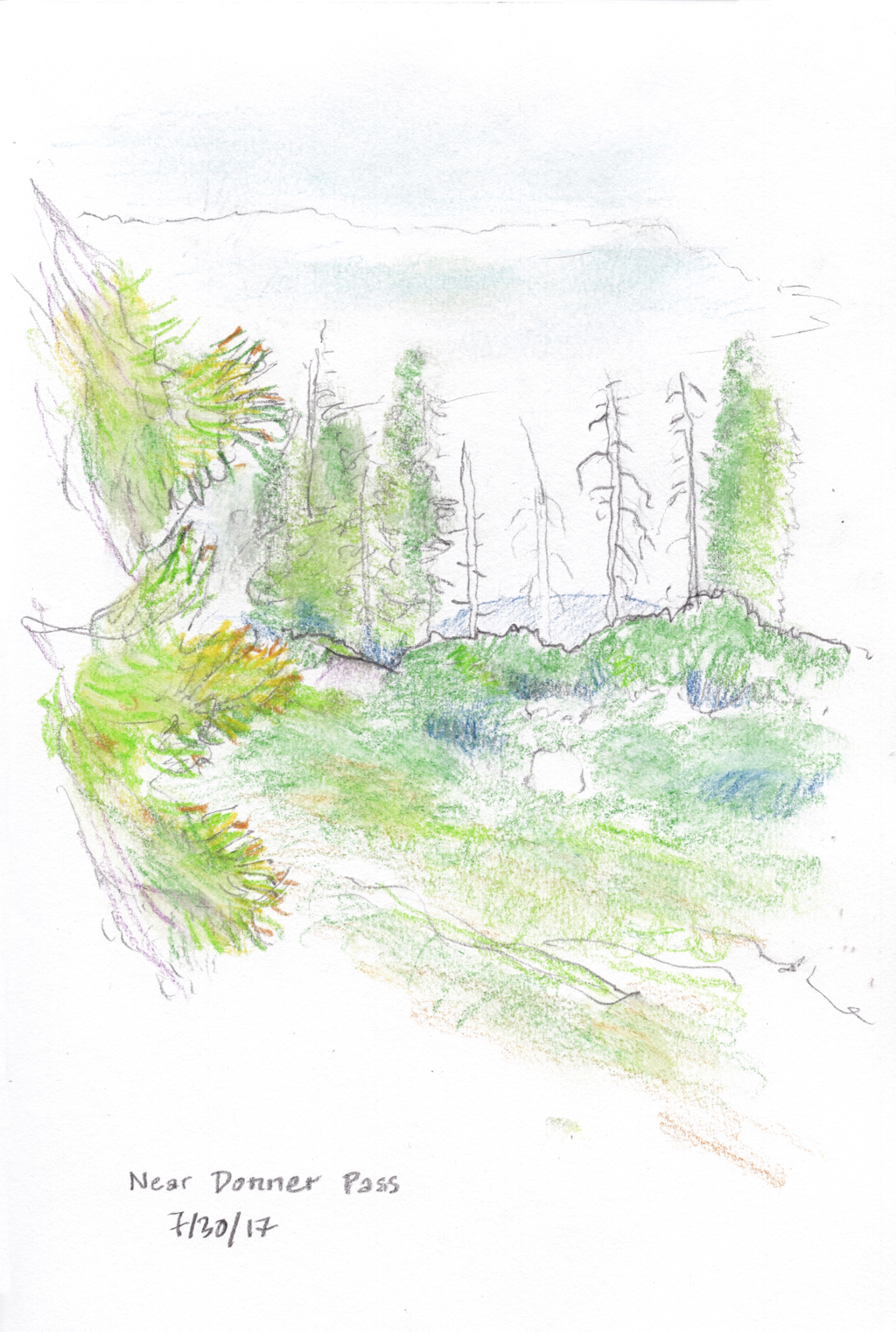

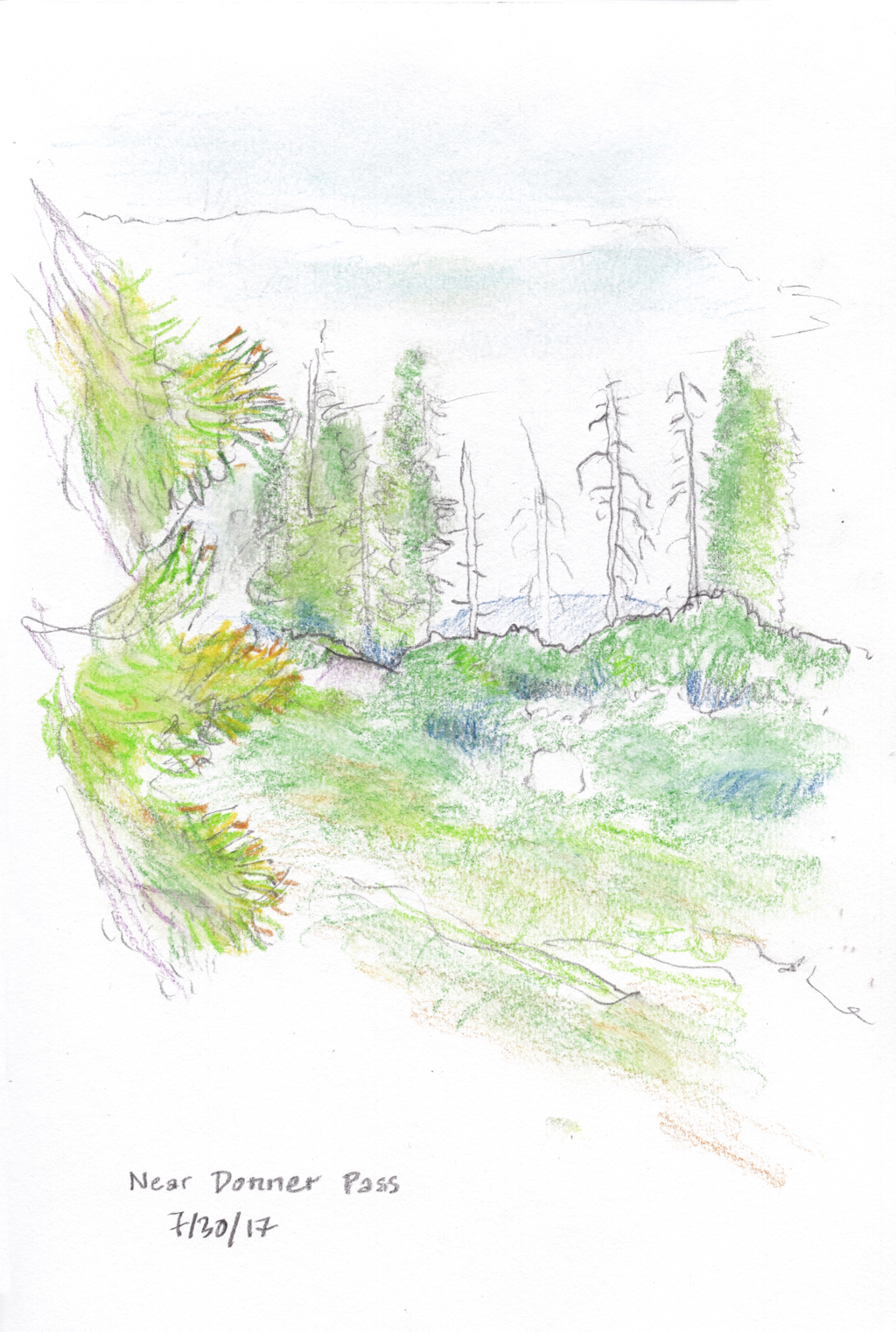

We said goodbye, and he walked abck to his truck while I walked out into the alpine forest that is slowly. What struck me most were the many tall white skeletons of dead pine trees which stand out among the remaining green trees. The Sierras have been ravaged by bark beetles, a native species that can kill trees that are stressed by drought. According to a March 28, 2015, article in the San Francisco Chronicle, “The beetle population is normally kept in check by the winter cold, but three years of above-average temperatures and lack of snowfall have given the growing bug hordes free rein to search and destroy.” This is yet another effect of global climate change. This past winter was cold and snowy, providing a respite for the trees this summer; but the trend of global climate change means that the bark beetle problem will soon return. I stood there and made a sketch: a few bleached trees standing out from trees and undergrowth that are bright green for now.

I briefly fantasized about continuing to walk along the Pacific Crest Trail, heading for Canada. But instead, I turned around and headed back to my car.

Note: Written on 8/2 from my notes.