Below is the uncorrected text of the talk with which I began a class on the mystical tradition within Unitarian Universalism, focusing (of course) on the Transcendentalists. A fascinating discussion followed, in which participants offered corrections where I was vague or in error, amplified things that needed to be amplified, and added lots of good thinking. So if you read this, remember that you’re missing the most interesting part of the class. Also, I diverged from the text at several places, so the talk you heard may not be the talk you read here.

Yes, liberal religion has a mystical tradition!

It seems odd that I have to assert this so vigorously. But our Unitarian and Universalist traditions, and Unitarian Universalism today, have not been particularly hospitable towards mystics. Throughout our history, and into the present day, the rationalists dominate our theological conversations — and I include both the theistic rationalists and the atheist rationalists. Our faith tradition clings to its belief in a rationalism inherited from the Enlightenment; we believe in carefully reasoned arguments; we have a tendency to focus on the brain and mind and ignore the heart and the rest of the body; we are most likely to use logical thought, and we are inclined to ignore other ways of knowing and interpreting the world.

However, by the same token, the mystics among us been not been kind towards their non-mystical co-religionists.

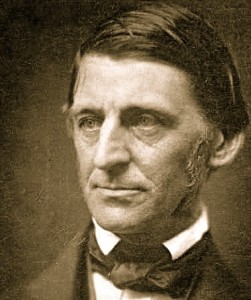

Emerson against religious formalism

Back in 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson gave what is now known as the Divinity School Address; he spoke to the graduating class of Harvard Divinity School, supplier of most Unitarian ministers of the day, and told them how to be good ministers. Do not be coldly rational formalists, he warned. And then, speaking of the minister of his Unitarian church in Concord, Massachusetts, a man by the name of Barzillai Frost, Emerson said:

“Whenever the pulpit is usurped by a formalist, then is the worshipper defrauded and disconsolate. We shrink as soon as the prayers begin, which do not uplift, but smite and offend us. We are fain to wrap our cloaks about us, and secure, as best we can, a solitude that hears not. I once heard a preacher who sorely tempted me to say, I would go to church no more. Men go, thought I, where they are wont to go, else had no soul entered the temple in the afternoon. A snow storm was falling around us. The snow storm was real; the preacher merely spectral; and the eye felt the sad contrast in looking at him, and then out of the window behind him, into the beautiful meteor of the snow. He had lived in vain. He had no one word intimating that he had laughed or wept, was married or in love, had been commended, or cheated, or chagrined.”

“Whenever the pulpit is usurped by a formalist, then is the worshipper defrauded and disconsolate. We shrink as soon as the prayers begin, which do not uplift, but smite and offend us. We are fain to wrap our cloaks about us, and secure, as best we can, a solitude that hears not. I once heard a preacher who sorely tempted me to say, I would go to church no more. Men go, thought I, where they are wont to go, else had no soul entered the temple in the afternoon. A snow storm was falling around us. The snow storm was real; the preacher merely spectral; and the eye felt the sad contrast in looking at him, and then out of the window behind him, into the beautiful meteor of the snow. He had lived in vain. He had no one word intimating that he had laughed or wept, was married or in love, had been commended, or cheated, or chagrined.”

Emerson was prone to really bad puns, and here he indulges himself in a hidden pun: It is Barzillai FROST who is speaking in a SNOW STORM; bad as this pun may be, it points up a difference between two kinds of coldness: there is the coldness of the snow, which is real and can be experienced; and there is the coldness of religious formalism. Continue reading “Mystics and Transcendentalists”

“Whenever the pulpit is usurped by a formalist, then is the worshipper defrauded and disconsolate. We shrink as soon as the prayers begin, which do not uplift, but smite and offend us. We are fain to wrap our cloaks about us, and secure, as best we can, a solitude that hears not. I once heard a preacher who sorely tempted me to say, I would go to church no more. Men go, thought I, where they are wont to go, else had no soul entered the temple in the afternoon. A snow storm was falling around us. The snow storm was real; the preacher merely spectral; and the eye felt the sad contrast in looking at him, and then out of the window behind him, into the beautiful meteor of the snow. He had lived in vain. He had no one word intimating that he had laughed or wept, was married or in love, had been commended, or cheated, or chagrined.”

“Whenever the pulpit is usurped by a formalist, then is the worshipper defrauded and disconsolate. We shrink as soon as the prayers begin, which do not uplift, but smite and offend us. We are fain to wrap our cloaks about us, and secure, as best we can, a solitude that hears not. I once heard a preacher who sorely tempted me to say, I would go to church no more. Men go, thought I, where they are wont to go, else had no soul entered the temple in the afternoon. A snow storm was falling around us. The snow storm was real; the preacher merely spectral; and the eye felt the sad contrast in looking at him, and then out of the window behind him, into the beautiful meteor of the snow. He had lived in vain. He had no one word intimating that he had laughed or wept, was married or in love, had been commended, or cheated, or chagrined.”