My cousin N. was telling me about how she went to a “chalice circle” conversation with her father. The subject for conversation was letting go. That topic got me to asking myself some more specific questions: what are those things where I don’t have any choice but to let go? (a completed project at work, a car that is so rusted out it’s dangerous to drive, who I was in the past); what are those things that I’d like to let go but can’t bring myself to do it? (a book given to me by my grandmother, the bicycle that causes grinding sounds in my knees, a poorly-written journal I once kept); what are those thing that would give me great pleasure to get rid of? That last question was the one I wanted to ask myself today. So I got rid of several boxes of books that I haven’t looked at in years, some old shoes I can no longer wear, a three foot stack of old magazines I didn’t even know I had, several years’ worth of old appointment books. Let it go, let it go! I dusted the shelves these things used to sit on, and now I can breathe more easily.

Category: Meditations

Woman’s relation to religious freedom (1892)

Back in 1892, Rev. Celia Parker Woolley, a feminist, antiracism activist, and Unitarian minister, gave a short talk on the need for women’s intellectual and spiritual freedom. In this talk she places freedom before love, and for this reason I think Woolley’s talk remains relevant: she is telling us that the problem is not whether to put family or career first, or how to “lean in” and have it all; the problem, simply put, is that women must have the same kind of freedom that men have.

Woman’s Relation to Religious Freedom

delivered during the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the First Unitarian Society of Geneva, Ill., 11 June 1892; stenographically recorded

[At a Saturday evening collation, the Chair called on Rev. Celia Parker Woolley to respond to the toast “Woman’s relation to religious freedom.”]

I have been wondering, Mr. Chairman, whether you stopped to consider the amount of moral dynamite in the selection of this subject, the combination of two such words as “woman” and “freedom.” It is a rather serious subject to me and I fear I shall not be able to treat it with that lightness and ease that belong to after-dinner efforts of this kind. It has prompted me to take a text, not from the Bible, but from one of our modern prophets, Olive Schreiner. It is from one of the shorter allegories in her latest volume of Dreams, and is entitled, if I remember aright, “The Angel of Life,” and runs as follows:

“The Angel of Life approached a woman sleeping, bearing a gift in each hand [Freedom in one hand, and Love in the other], and saying to the woman ‘Choose.’ The woman waited long and finally chose— Freedom. The Angel smiled and said ‘That is well. Hadst thou chosen the other I would have given thee thy choice, but I should have gone away, not to return. Now I shall return, and when thou see’st me again, I shall bear both gifts in one hand.’ (Note 1)

There is a profound truth in this little fable whether you regard the sleeping woman as typical of the entire race of men and women together, typical of both as truth-seekers, or whether you take the figure as standing for woman alone, in her search for a higher and more complete womanhood. It leads us also to think of the comparative merits of love and freedom as factors of growth. I don’t know that I would go so far as to say that a broader and truer synthesis is reached in the word Freedom than the word Love, but I certainly feel that the last word is used in often a very injurious and misleading way. I hear much preaching of love in the pulpits that offends both my taste and judgment, still, undoubtedly love is the grander, more inclusive word than any other in our human speech, when rightly used. What the allegory means to teach is, I think, that if Love is the word defining the spirit that governs all things, Freedom is the word which defines that method of growth by which we reach the truest conception of love and become its helpful ministers.

Historically, the allegory does not speak the truth. Historically, as a matter of fact in her own personal experience and that of her race, woman has never chosen freedom before love. On the contrary, all her choices have been those of love, those choices represented in the various relations in life which she has been called on to sustain, of society, the family, the church. So that when we try to talk about woman’s relation to freedom, or to religious freedom, we seem to have little to say. We should find a great deal to say if we were to speak of woman’s relation to religion. Then we could speak of her zeal, her devotion, her piety, the large numbers she has always brought to the support of the church compared with man. But when we remember how often that devotion has been purchased at the cost of real intelligence on her part, how her zeal has generally stood for bigotry and ignorance, then we see the difficulty of saying much in her favor on this special subject. But the past is one thing, the future another, and my subject is justified by the hope and the promise held out to woman and to the world through her, in this era of awakening intelligence and responsibility in which we live.

Today, we stand at that point in the development of religious thought, or rather in the development of all thought, when freedom is seen to be a necessary condition of intellectual life. Socially, religiously, domestically, woman never enjoyed that degree of liberty that is given her to-day, freedom to use her own mind and heart in solving the problems of life, that comes to her not as a woman but as a human being. To be of great worth to the world and to man she must cultivate all her powers unhindered, must make the most and best of herself. She must choose freedom first, before love, or love will be unworthily chosen. As I think of this, and remember how complex are all the relations of life, see how much of pain, misunderstanding and seeming wrong such choice on woman’s part means, I see how the strain and pain of new growth must be felt by man as well as by her, how she has in some respects the easier task, since she has but to choose for herself; while man who has so long held the reins of privilege, influence and authority must make her choice his, choosing freedom for her with freedom for himself. Men have much to learn and suffer here.

In their religious life women have had a voice and influence only on the lower plane of the church’s practical work. Woman has contributed too little to the thought the higher spirituality of the church. Men will be her natural leaders here for a long time to come. Not until she has learned to think independently as well as reverently will her relation to the coming creed founded on perfect mental liberty, be established.

— ed. T. H. Eddowes, Frances Le Baron, and George Brayton Penney, Fifty Years of Unitarian Life: Being a Record of the Proceedings on the Occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Organization of the First Unitarian Society of Geneva, Illinois, Celebrated June Tenth, Eleventh, and Twelfth, 1892 (Geneva, Ill.: Kane County Publishing, 1892), pp. 122-124.

Notes

(The story as actually printed in Schreiner’s book reads as follows:)

Chapter VIII: Life’s Gifts

I saw a woman sleeping. In her sleep she dreamt Life stood before her, and held in each hand a gift — in the one Love, in the other Freedom. And she said to the woman, “Choose!”

And the woman waited long: and she said, “Freedom!”

And Life said, “Thou hast well chosen. If thou hadst said, ‘Love,’ I would have given thee that thou didst ask for; and I would have gone from thee, and returned to thee no more. Now, the day will come when I shall return. In that day I shall bear both gifts in one hand.”

I heard the woman laugh in her sleep.

— Olive Scheiner, Dreams, “Author’s Edition” (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1891), pp. 115-116.

Peach Blossom Spring

“Peach Blossom Spring,” or “Peach Blossom Fountain,” is a well-known Chinese story by T’ao Yuan-ming, whose literary name was T’ao the Hermit (or recluse). I put part of this story on an earlier blog post here, and am finally posting the whole story, in this translation Herbert Giles, Gems of Chinese Literature, pp. 107-108:

Somewhere around the year 390, when the north of China had been conquered by the Mongol invaders from central Asia, and refugees from the invasion filled the south, there lived a fisherman in the village of Wu-ling. These were the years when the emperors of the Ch’in dynasty sat on the throne of China. The Ch’in emperors were powerful, and while some people said they did what had to be done in the face of barbarian invasions, there were others who said that government officials were too often vain and greedy, and did not have the interests of the ordinary people at heart.

To get back to the fisherman of Wu-ling:

One day, this fisherman was out on the river, and he decided to follow the river upstream. When he came to a place where the river branched, he took the right or left branch without paying attention to where he was going.

Suddenly he rounded a bend in the river and came upon a grove of peach-trees in full bloom. These peach trees grew close along the banks of the river for as far as he could see, until the next bend in the river, with not a tree of any other kind in sight. The fisherman was filled with surprise at beauty of the scene and the delightful perfume of the flowers. He continued upstream, wondering how far along the river these trees grew.

At last he came to the end of the peach trees. By now, this branch of the river was scarcely bigger than a stream, and here also the river ended, at the foot of a hill. But in the side of this hill there was a cave. A faint light was coming from the cave, so the fisherman tied up his boat to a tree, and crept in through the narrow entrance of the cave.

So he made fast his boat, and crept in through a narrow entrance, which shortly ushered him into a new world of level country, of fine houses, of rich fields, of fine pools, and of luxuriance of mulberry and bamboo. Highways of traffic ran north and south; sounds of crowing cocks and barking dogs were heard around; the dress of the people who passed along or were at work in the fields was of a strange cut; while young and old alike appeared to be contented and happy.

One of the inhabitants, catching sight of the fisherman, was greatly astonished; but, after learning whence he came, insisted on carrying him home, and killed a chicken and placed some wine before him. Before long, all the people of the place had turned out to see the visitor, and they informed him that their ancestors had sought refuge here, with their wives and families, from the troublous times of the House of Ch’in, adding that they had thus become finally cut off from the rest of the human race. They then enquired about the politics of the day, ignorant of the establishment of the Han dynasty, and of course of the later dynasties which had succeeded it. And when the fishermen told them the story, they grieved over the vicissitudes of human affairs.

Each in turn invited the fisherman to his home and entertained him hospitably, until at length the latter prepared to take his leave. “It will not be worth while to talk about what you have seen to the outside world,” said the people of the place to the fisherman, as he bade them farewell and returned to his boat, making mental notes of his route as he proceeded on his homeward voyage.

When he reached home, he at once went and reported what he had seen to the Governor of the district, and the Governor sent off men with him to seek, by the aid of the fisherman’s notes, to discover this unknown region. But he was never able to find it again. Subsequently, another desperate attempt was made by a famous adventurer to pierce the mystery; but he also failed, and died soon afterwards of chagrin, from which time forth no further attempts were made.

Giles claims the story is really about how childhood innocence can never be recovered, and I suppose that’s a valid interpretation, but I don’t find it a compelling interpretation. The story could also be read as being related to Hesiod’s Age of Gold (Works and Days, ll. 109–201), that time when humankind was in an ideal state; or a story related to the ancient Hebrew story of a Garden of Eden; but both Hesiod and the ancient Hebrew story make it clear that the early age of innocence ended at some point, while in the country of the Peach Blossom Spring that age continues. I prefer to interpret this story as a utopian vision, and thus as a critical commentary on contemporary political realities. Or the story could mean all of these things, or none of them, and really we will never know for the way to the land beyond the Peach Blossom Spring has been lost.

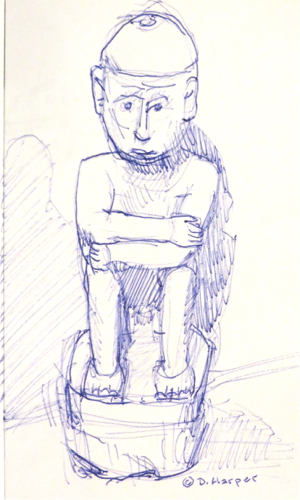

Ceremonial deity, Phillippines

Above: Sketch of a “ceremonial deity,” Philippines, c. 1930. Wood and shell. Asian Museum of Art.

One of delights of going to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco is seeing the diversity of depictions of deities. Today I particularly noticed the unnamed deities — like this sculpture of an unnamed ceremonial deity, made in the Philippines around 1930. Why do we not know the name of this deity? Is it because it is a minor deity, and thus not widely identifiable (though perhaps readily identifiable by a devotee)? Did it never have a name that could be spoken by humans? Or was this a deity like the Roman Lares familiares, the household gods, who don’t seem to have had names, or whose power was so geographically restricted that their names perhaps were known only to the household they protected?

I think that the end of Christendom is allowing us to see such minor deities more clearly. In the worldview of Christendom, only the major deities — the wildly transcendent deities, Jehovah’s direct competition — were worthy of serious attention. Now maybe we can pay a little more attention to the many minor deities who inhabit the metaphorical space between those distant transcendent deities and mortal creatures.

Photographing butterflies

I took a break from curriculum development on Tuesday and drove down to Pinnacles National Park. Of course I looked at the incredible rock formations for which the park is famous. But as spectacular as the scenery was, the highlight of the trip was watching butterflies in Bear Gulch. In particular, I spent about ten minutes watching one Western Tiger Swallowtail visiting larkspur blossoms. I took a great many photographs of this one butterfly, getting as close as I could. With a photograph, you can capture narrow slices of time: the position the butterfly’s wings take as it balances on a flower; the way it clings to the flower with its legs and arches its head towards a blossom; the moment when the butterfly is just approaching the flower:

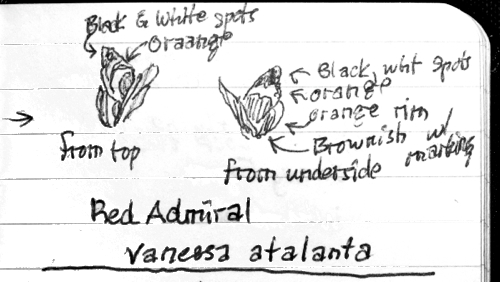

But sometimes what sticks in your memory is not what you actually saw, but the photographs of what you saw. After I left Pinnacles, I drove to Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve. When I saw butterflies there, I made a point of trying to sketch them in my field notebook rather than just photograph them, like this common butterfly:

This sketch, as an end product, is not nearly as attractive as a photograph (and I did take a photograph of this insect as well) — it’s not as attractive, but I learned more about butterflies by making this sketch. By comparing my sketch to a field guide, by seeing what I left out, I learned what I don’t see when I look at butterflies. I suspect making less attractive sketches like this does more towards sharpening my powers of observation than does taking a great many very attractive photographs.

Web of relationships

Today I was at Pescadero Marsh to look at live birds, but the dead things proved more interesting. It was just after low tide, and I saw two empty crab shells (prob. Red Crabs, Cancer productus), looking as though they had been eaten by gulls; interesting, but a pretty common sight, and it’s more interesting to actually see a gull eating a crab. Then I found the empty shells of two small crustaceans, organisms I’d never seen before. Here’s one of them:

I have no idea what species this is, though I suspect it’s a fairly common organism.

Later, I walked along the dike near Butano Creek, and came across a dead mole (the notebook next to the mole is marked in inches):

Given the size of those front feet and the short tail, I’d say it was a Broad-footed Mole (Scapanus latimanus). This is the third dead mole I’ve found in six months.

What interests me when i see dead things in the field is trying to figure out how they died, and how they are tied in to the ecosystem. The Red Crabs were easy to figure out — probably eaten by gulls. But why did that little crustacean die? it didn’t look as though another organism had tried to eat it, so was it simply left high and dry at low tide? As for the Broad-footed Mole, there was a definite hole in the other side of the animal, which could have been made by a bird’s bill; I saw Red-tailed Hawks and Northern Harriers hunting in the marsh; perhaps a raptor killed the mole, then got scared away before it could eat.

These are just possible scenarios; I’ll never know what really happened; but what I do know is that somehow these dead creatures reveal something about the web of relationships between organisms.

Ants

Recently, I stumbled across the AntWeb site, sponsored by the California Academy of Sciences. Once you create a login (and all you have to provide is a username and password, no other info), you have access to tons of photographs of ant specimens, taken through a powerful microscope. Of particular interest to me is the online field guide to California ants, with photos of nearly all of the 270 resident species. The curator of the California pages writes:

“Prominent California ants include seed-harvesting species in the genera Messor, Pheidole and Pogonomyrmex; honeypot ants in the genus Myrmecocystus; a diverse array of species in the genera Camponotus (“carpenter ants”) and Formica; native fire ants (Solenopsis spp.); velvety tree ants (Liometopum spp.); and the introduced Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). This last named species is particularly common in urban and suburban parts of California, where it establishes dense populations and eliminates most native species of ants.”

I’ve always thoughts ants were interesting creatures. Now having looked through dozens of photos of ants I will go further and say that they are beautiful creatures. Even the Argentine ant appears beautiful, in spite of the destruction it does to native arthropods.

I am also fascinated by the written descriptions; these descriptions have their own kind of beauty, which may be found in their economy and laconic precision. Here, for example, is how to identify the Argentine ant — remembering that you will need a powerful binocular microscope to see all these details:

“Diagnosis among workers of introduced and commonly intercepted ants in the United States. Antenna 12-segmented. Antennal scape length less than 1.5x head length. Eyes medium to large (greater than 5 facets); do not break outline of head; placed distinctly below midline of face. Antennal sockets and posterior clypeal margin separated by a distance less than the minimum width of antennal scape. Anterior clypeal margin variously produced, but never with one median and two lateral rounded projections. Mandible lacking distinct basal angle. Profile of mesosomal dorsum with two distinct convexities. Dorsum of mesosoma lacking a deep and broad concavity; lacking erect hairs. Promesonotum separated from propodeum by metanotal groove. Propodeum with dorsal surface not distinctly shorter than posterior face; angular, with flat to weakly convex dorsal and posterior faces. Propodeum and petiolar node both lacking a pair of short teeth. Mesopleura and metapleural bulla covered with dense pubescence. Propodeal spiracle bordering posterior margin of propodeal profile. Waist 1-segmented. Petiole upright and not appearing flattened. Gaster armed with ventral slit. Erect hairs lacking from cephalic dorsum (above eye level), pronotum, and gastral tergites 1 and 2. Dull, not shining, and color uniformly light to dark brown. Measurements: head length (HL) 0.56–0.93 mm, head width (HW) 0.53–0.71 mm.”

Time, like the tide, sweeps over the new year

The following poem appears in A Collection of Hymns on the Most Important Subjects of the Gospel, edited by Thomas Humphrys (Bristol, England: Biggs & Cottle, 1798), pp. 14-15, as a meditation on the new year:

My days, my weeks, my months, my years,

Fly rapid like the whirling spheres

Around the steady pole;

Time, like the tide, its motion keeps,

Till I shall launch those boundless deeps

Where endless ages roll.

The grave is near the cradle seen,

How swift the moments pass between

And whisper as they fly;

“Unthinking man remember this,

“Thou midst thy sublunary bliss

“Most groan, and gasp, and die.”

Eternal bliss, eternal woe,

Hangs on this inch of time below,

On this precarious breath:

The God of nature only knows,

Whether another year shall close,

Ere I expire in death.

Long ere the sun shall run its round,

I may be buried under ground,

And there in silence rot;

Alas! one hour may close the scene,

And ere twelve months shall roll between,

My name be quite forgot….

These late-eighteenth century sentiments probably soundm foreign to most early-twenty-first century American minds. Contemporary American culture insists we be optimistic about the future, so this poem may strike you as morbid. Certainly I do not agree with the theology of the poem, which the poet goes on to wonder whether he or she will go to heaven or hell after death, and in the concluding verse prays: “Help me to choose that better way” that will lead to heaven.

Yet though I do not agree with the theology, it’s not a bad idea to remember that death is just around the corner. We needn’t think obsessively about death and dying, but it can be freeing to realize that many small things that loom large in daily life are not that important. What is important is striving to be the best person possible, which in turn should help us realize that self-reflection and self-knowledge take priority over striving to buy consumer goods or striving to get a promotion at work or striving to get your children into Ivy League schools. In this realization lies freedom.

I don’t know who wrote the poem originally. Humphrys does not attribute this poem to a specific author. Another version of this poem was printed in The Poetical Monitor: consisting of pieces select and original for the improvement of the young in virtue and piety: intended to succeed Dr. Watts’ Divine and moral songs, etc., edited by Elizabeth Hill (London: Shakespear’s-Walk Female Charity School, 1796), pp. 64-65. The poem appears under the tile “On the Eve of the New Year,” and Hill lists the author as “Green.” Perhaps an astute reader can track down the author. Continue reading “Time, like the tide, sweeps over the new year”

The radiant life

Last week, Dad spent quite a bit of time talking with my sisters and me about World War II. I think it is very difficult for us now to understand how traumatic those war years were, and to understand how the war and trauma affected those who lived through it; they were dark years indeed.

When Dad was at college right after World War II, he took a philosophy course with Rufus Jones, the great Quaker philosopher and theologian. He still has several books by Jone on his bookshelf, and while I was looking for something to read this morning, I pulled out Jones’s The Radiant Life, published in 1944, in the middle of the war. The book represents Jones’s search for “gleams of radiance” which might be found “in spite of the darkness of the time.”

Like his contemporaries, the Unitarian theologian James Luther Adams and Reinhold Niebuhr, both of whom were also profoundly affected by the war and by the evils perpetrated by Nazi Germany, Jones felt he could no longer cling to the sunny optimism of the Progressives, nor to the even sunnier optimism of Emerson. Where, then, should we turn to find gleams of light? James Luther Adams turned towards the social structure of voluntary associations: finding light in building robust communities that could move us towards the good. Reinhold Niebuhr turned towards pragmatism and Christian realism: accepting that in a corrupt world we may not find all the light we need (this, I believe, is the origin of Neibuhr’s famous “Serenity Prayer).

Jones, Quaker that he was, found a different answer to the traumas of the mid-twentieth century Western world: he encouraged us to accept the reality around us but also to look for the light that was always there. He wrote:

“The Kennebago Mountains are visible in the far horizon of my home in Maine, but they come into sight only when the wind is north-west and has blown the sky clear of fog and mist and cloud. Then there they are, in all their distant purple glory. But we know that they are there all the time, when the wind is east or south, though we cannot see them, and we say to our visitors, wait until the wind comes round and blows from Saskatchewan, and then you will see our mountains which are over there in our far sky-line! Some persons’ lights up like that only when the wind is in the right quarter. I am pleading for a type of life that is sunlit and radiant, not only in fair weather and when the going is smooth, but from a deep inward principle and discovery which makes it lovely and beautiful in all weathers.”

I think I like Jones’s approach better than either Adams or Neibuhr — not that I think that any one of them has the final and complete truth of the matter, nor the final answer to the traumas of life; no single human being can ever know the complete truth of anything. But to know that the mountains are always there, even when you can’t see them because they are obscured — that is worth remembering. I can see why my father liked Jones so much, and continues to like him. Adams focuses on human relations, which I admire, but I sometimes wish Adams let in a little more of Emerson’s sunshine. However, Emerson is too sunny, except in his poetry, and sometimes I can’t quite believe him. Niebuhr is too dark, and I don’t want to believe him.

How do we get through the traumas of contemporary life? How do we get through the horrors of war and terror? How can we face the damage humans are doing to the rest of creation? How can we make it through the struggles of human life, of grief and death and all the rest? I like Rufus Jones’s answer: remember that the mountains are always there even when you can’t see them. Or, to put it another way, look for the gleams of light which always may be found even in the darkest of times.