Carol and I went to Pescadero Natural Preserve today. It was delightfully cool (about 70 degrees) with high fog blocking much of the sun. The tide was quite low when we arrived, so I wandered around looking at the variety of organisms in tide pools: sea anemones, crustaceans, molluscs, seaweeds, etc. Then we decided to walk to the mouth of Pescadero Creek and head up into the marsh.

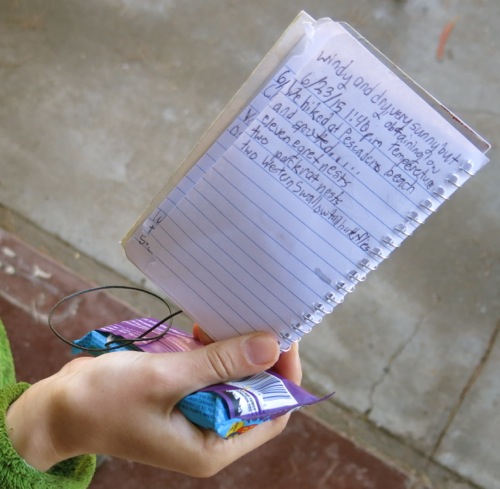

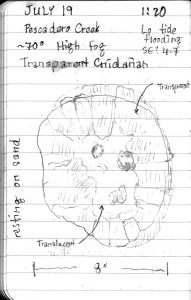

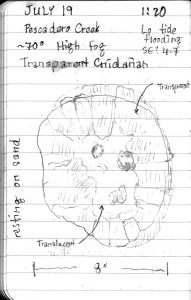

As we followed the creek upstream under the Highway 1 overpass, Carol noticed that there were dozens of jellyfish washed up along the high tide line, translucent organisms looking a little like plastic bags filled with water. Most of the organisms were damaged; some had obviously been stepped on, some appeared to have broken in pieces, some no longer had a definable shape. I walked closer to the water, and began to find a few organisms that looked less damaged; one in particular, shown in the photograph below, retained a good deal of its structure:

When we got home, I did some online research to find out what kind of Cnidarian this was. I concluded it was a Moon Jellyfish, the common name of Aurelia species; most likely Aurelia labiata, which the authorities I consulted online agreed was the Aurelia species found along the San Mateo County coast. More specifically, what I saw was most likely the central morph of Aurelia labiata, the type specimen of which came from Monterey Bay (M. N. Dawson, Macro-morphological variation among cryptic species of the moon jellyfish, Aurelia [Cnidaria: Scyphozoa], Marine Biology [2003] 143:369-379).

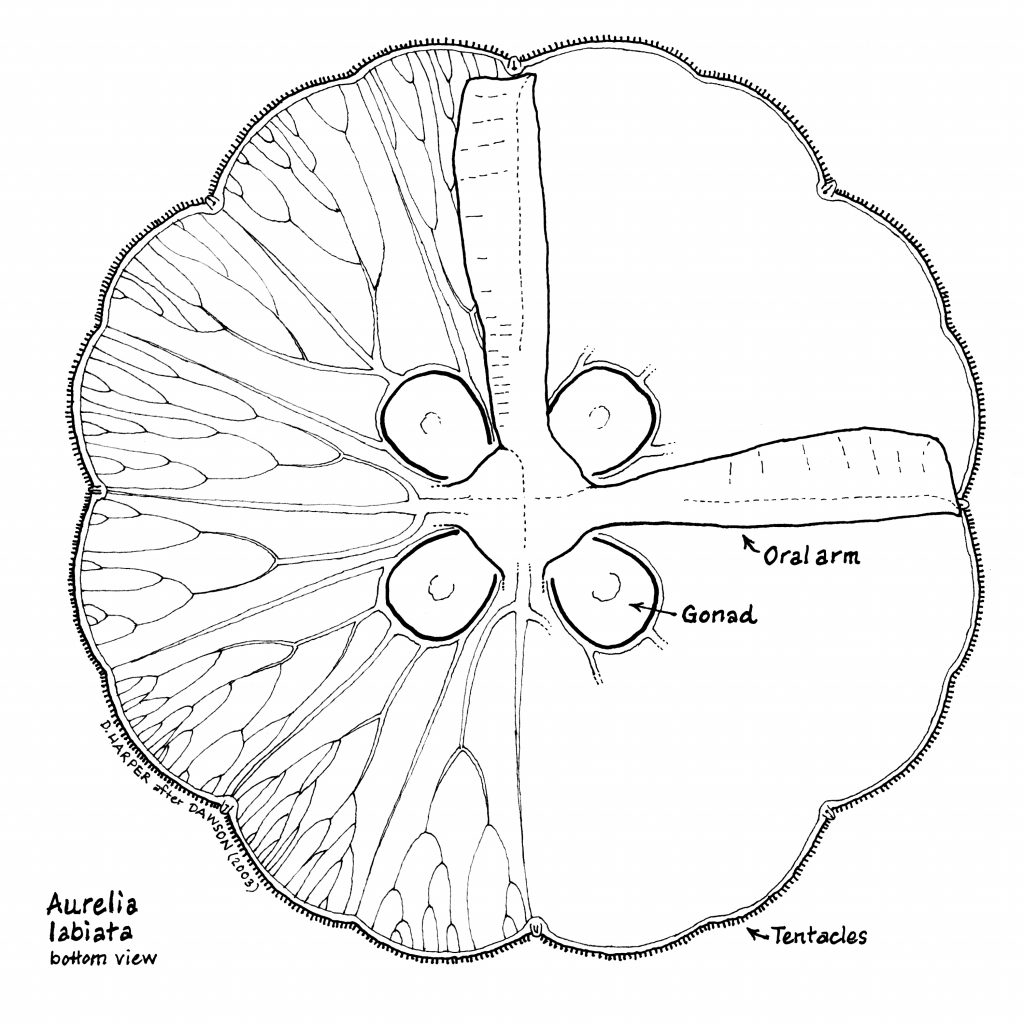

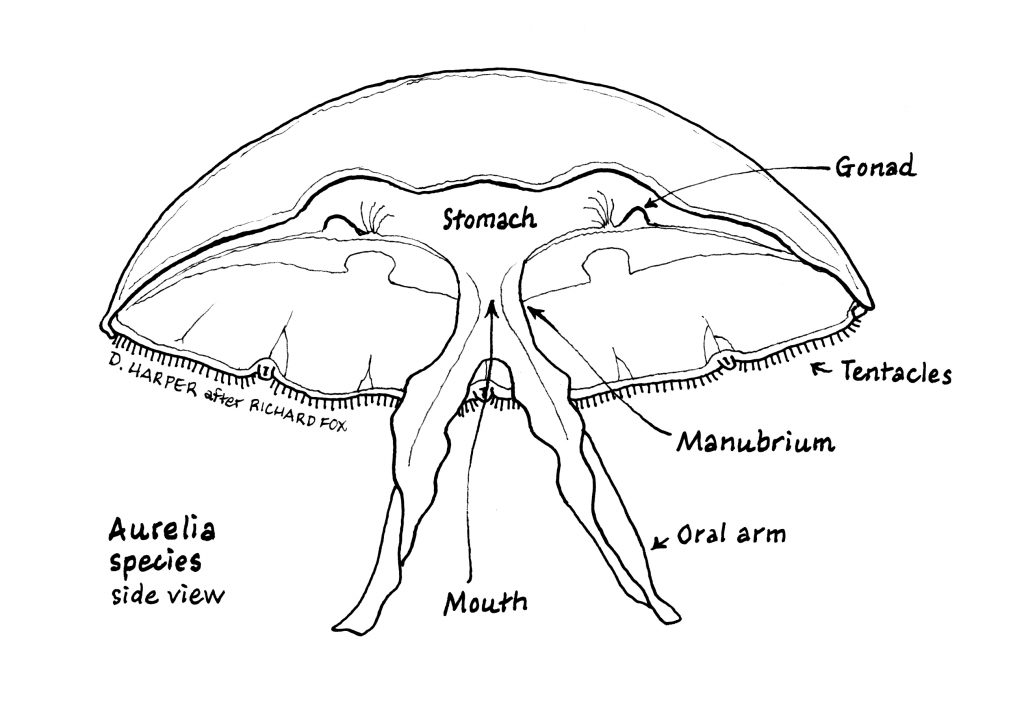

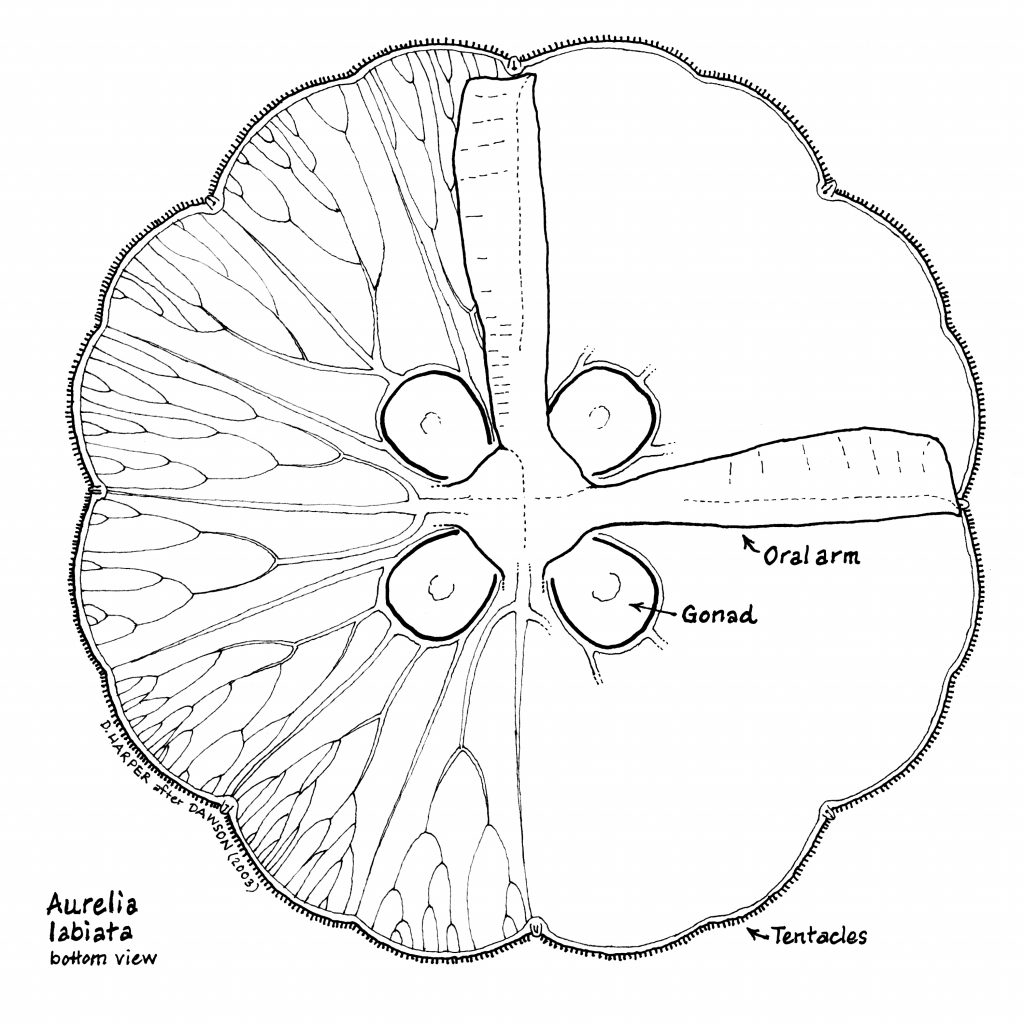

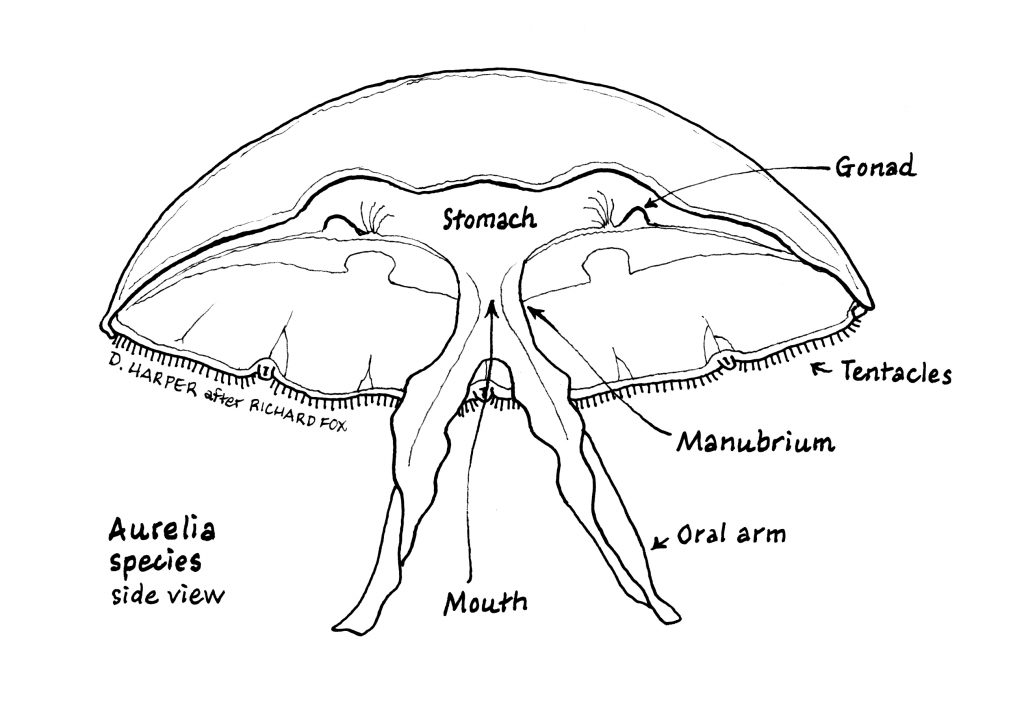

Based on this tentative identification, I made two drawings of some of the structures that might be seen in the photograph. The first is based on Dawson (2003), and shows the organism from the underside; this approximates what you see when the jellyfish is lying flattened out on the sand, as in the photograph. The second drawing, based on a drawing by Richard Fox of Lander Univ., shows the organism as if it were alive and floating in the water.

The gonads are clearly visible in the photograph (note that the gonads and gastric pouch are right next to one another, so the gastric pouches are also visible). The manubrium and stomach in the center show fairly clearly. I did not see any tentacles when I looked at the organism, and none are visible in the photograph; this is not surprising as they would be quite small. Some of the radial canals are visible, enough to give the sense that the organism has radial symmetry. But the organism in the photo appears to have disintegrated somewhat.

The organism I photographed, and most of the Moon Jellyfish I saw stranded along the creek, were clear to translucent. One of them, though, was amber-colored; others had dark red or purple structures. The Encyclopedia of Life Web page on Moon Jellyfish, citing an article by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, states that Aurelia labiata are translucent when young, turning “milky white, sometimes with a pink, purple, peach, or blue tint” at maturity. So most of the individuals I saw were, apparently, young jellyfish.

Carol and I walked around the marsh for a couple of hours, and came back to the creek as the tide was beginning to flood again. I watched the tide pick up some of the stranded jellyfish, hoping to see some signs of life. One or two of the jellyfish floated away, looking intact, with their bells extended; perhaps they survived their exposure. But most of them sank beneath the water, or crumpled up, or seemed to be coming apart; it seems very unlikely these individuals survived.

Drawings revised, July 20.

Drawings revised, July 20.

More info: Article on Aurelia labiata on the Animal Diversity Web provides links to several academic references.

Note on my drawings: In making the drawings, I began with the cited sources, then consulted various online photos identified as Aurelia labiata. I saw significant variation in online photos, especially as regards tentacle length; since my drawings are not made from living specimens, they should be taken as schematic drawings, not accurate representations of live individuals.

Drawings revised, July 20.

Drawings revised, July 20.