On March 21, 1924, in Reading, Pennsylvania, 27 year old Dorothy Fassnacht Harper gave birth to her first child. The new baby was named Daniel Robert after his father, though he was called Bobby.

Bobby’s father, Dan, had gone to college to study for the ministry, and while he was in seminary served for two years as a minister in the Evangelical Association, a German-language Methodist group. But Dan found out that ministry was not for him, so he became a newspaperman, starting as a sportswriter, and then moving into other jobs in local newspapers in Scranton, Reading, and Hazelton, Pennsylvania. Bobby’s mother, Dorothy, was the daughter of a minister in the Evangelical Association, and her father officiated at her wedding to Dan in 1921. She completed the eighth grade, then worked as a dressmaker before her marriage. Bobby’s younger brother, Lee, was born in 1928.

The Great Depression hit the year after Lee was born. Dan found it hard to find steady work. In 1932 he got a job as a rewrite man with the Staten Island Advance, Staten Island, New York, far from Pennsylvania Dutch country where he had and Dorothy had always lived. He went by himself at first, not wanting to move his family until he was sure the job was going to last. It turned out to be a good job; according to his obituary in the New York Times: “Within four years, he was promoted successively to night editor, city editor and editor.” For the rest of the Depression, and until his retirement, Dan had a steady, secure job.

Dorothy, Bobby, and Lee followed Dan to Staten Island later in 1932. When Bobby started school in Staten Island, he ran into a problem with his name. He later wrote that his “name was changed from D. Robert to Robert when the New York City school system refused to allow any student to have an initial before a name.”

While Bobby did reasonably well at school, he had a lot of outside interests, too. Both he and Lee joined his father on fishing trips, and to the end of his life he kept photographs of fishing trips and strings of fish the three of them caught. He once wrote that the point of fishing was not necessarily to catch a lot of fish: “I remember my great uncle Spencer Fassnacht saying, after four of us had fished all day without catching anything, that seeing a kingfisher catch a fish had made it a good day.”

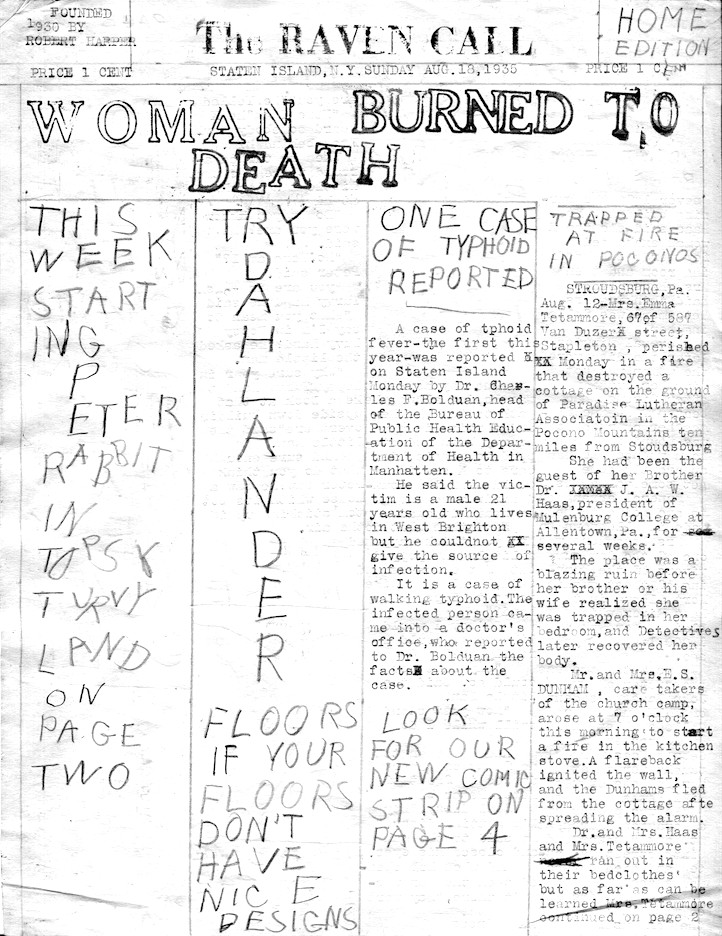

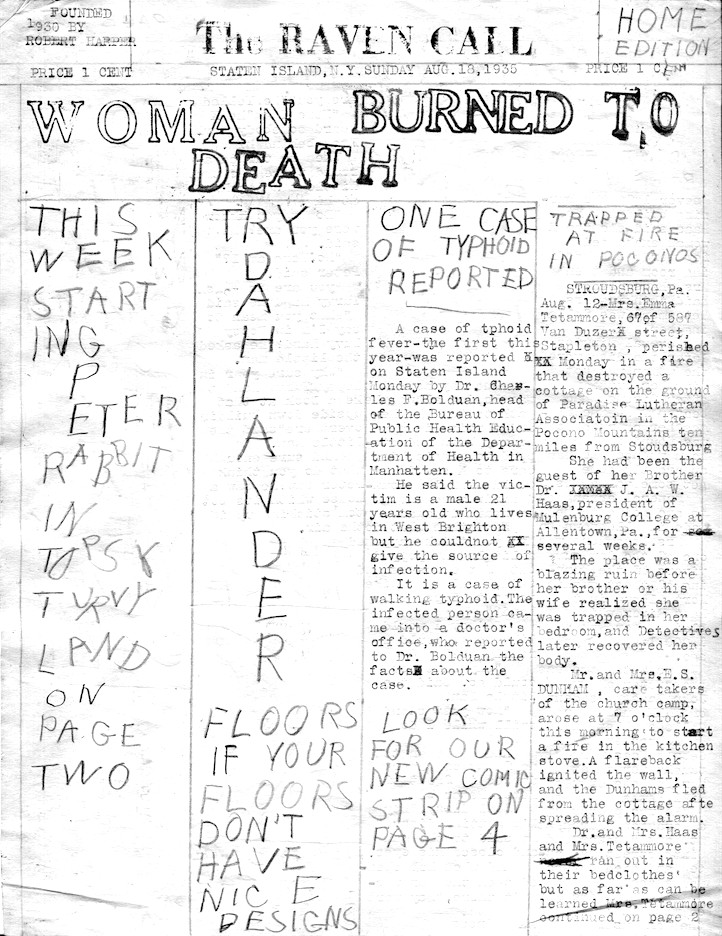

By the time he was ten or twelve, he started a neighborhood newspaper. Although some issues of this newspaper, “The Raven Call,” didn’t have much content, there were some real stories, too. The front page headline for the August 18, 1935, edition screamed, “WOMAN BURNED TO DEATH,” and the next story arrested your attention with the headline, “ONE CASE OF TYPHOID REPORTED.”

Bobby liked to read, and I have a few of his childhood books. On the title page of one of them, “Mark Tidd in Business,” part of a juvenile series by Clarence Budington Kelland, he wrote in pencil, “THIS BOOK BELONGS TO ROBERT HARPER GRADE 6B5”; above that I’m a little surprised to see that I inscribed my own name when I was a child; I have a vague recollection that my grandmother gave me the book. Another book he gave me when I was young was “Ken Ward in the Jungle,” a book from a juvenile series by Zane Grey, and though he didn’t write his name in it he told me it was his when he was a boy. I also have his tattered copy of Ernest Thompson Seton’s “Two Little Savages,” which I took from his condo when we were getting rid of all his books just before he died. Other books of his I remember seeing when we went to visit my grandmother in Staten Island include Jules Verne’s “Journey to the Center of the Earth” and “Their Island Home.” None of these is what you’d call a serious book.

He did not remember rebelling when he was a teenager. He later wrote: “In the middle of the Depression we were thankful that my father had a job. So many of my friends had fathers who had been employed in the shipyards on Staten Island before the Depression. Now they were lucky if they occasionally found jobs as carpenters or laborers…. I seldom heard of any teenagers rebelling. I do remember two of my acquaintances who rebelled. Norman Schaeffer, whose father was a doctor, had enough money to buy an old model A Ford in which he and several others would ride around in defiance of the law (the legal driving age in NYC was 18 at that time). Perhaps rebellion is a luxury that is more likely to occur among those who are well enough off to be bored and then resent the adult world. I and most of my high school friends simply tried to keep our noses clean.”

When he got into high school, Bobby got interested in physics and electronics. He doggedly did the work required of him in school, and at home wrapped himself up in his hobbies of model railroading and radio. He was thrilled the first time he heard the sound of a distant radio station come out of a radio he had built. After graduating from Port Richmond High School, he entered Haverford College, an obscure Quaker college in southeastern Pennsylvania, in September, 1942, intending to study physics.

Two weeks into his second semester, he was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Corps. He served overseas, in the European theatre, as a ground-based radio operator mechanic in the 437th Troop Carrier Group. He was part of the Headquarters Battalion, and was stationed in England and France during the invasion of France and Germany.

He didn’t talk much about his war years, though he did say that he never saw a shot fired in anger, and that those three years in the service were almost entirely unpleasant. He was fortunate to be part of the ground crew; he told us how he’d be talking (using Morse code, not voice) with a returning bomber when suddenly their signal would disappear; they had been shot down. He told us of another time when a plane came back carrying paratroopers returning from a mission; when they got off the plane, they just kept walking past their officers, and they walked right off the base. When he told this story towards the end of his life, he said the paratroopers told their officers to fuck off.

His mother saved his letters home, and I read them all not long before his death. I read some of the letters aloud to him, while he was still capable of understanding them. One of the last conversations I had with him, before he became unable to speak, was about how he finally realized at the end of his life that he had post-traumatic stress disorder from the war. Unfortunately, his letters from the war years disappeared when we were cleaning out his condo, but I remember the tone of the letters growing darker as the war dragged on. He had some kind of romance, or maybe more than one, and I’m pretty sure he lost his virginity in England. When I was in my forties, he gave me a self-published book by a friend of his from Haverford College, which he said accurately reflected his experiences; a significant part of that book concerned the sexual experiences of the protagonist. By this point in his life, I can no longer think of him as “Bobby,” so I’ll start calling him Bob.

After the war ended in Europe, Bob was put on a ship across the Atlantic, the first leg of a trip that was supposed to take him to the Pacific theatre. While he was in transit, the atom bombs were dropped and Japan surrendered, and he was discharged from the Army on September 25, 1945. Two days later, he was back at Haverford College, having received special permission to start school at the last minute.

To be continued…

[Updated Feb. 10 to remove errors.]