Another in a series of stories for liberal religious kids, this one from the Mahabharata. Adapted from The Indian Story Book: Containing Tales from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and Other Early Sources, by Richard Wilson (London: Macmillan & Co., 1914).

One day, near the end of their long exile in the forest, King Yudhisthira and his four brothers were searching for a mysterious deer which had stolen the wooden blocks which a Brahmin needed so he could light the sacred fire. The king and his brothers wandered deeper and deeper into the forest trying to find the deer. They grew more and more thirsty, but they were unable to find water. At last they all sat down, exhausted, beneath a tall tree.

“If we do not find water soon, we shall surely die,” said Yudhisthira He turned to his brother Nakula. “Brother,” he said, “climb the tree for us and see if you can spot water nearby.”

Nakula quickly climbed the tree, and in a few moments called down, “I see trees which only grow near running water, and there I hear the sound of cranes, birds which love the water.”

“Take your quiver,” said Yudhisthira. “Go fill it with water, and bring it back to quench our thirst.”

Nakula set out, and quickly found a small stream which widened into a pool of clear water with a crane standing on the far side.

Nakula knelt down at the edge of the pool to drink. Suddenly a stern Voice spoke: “Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Nakula was so thirsty he ignored the Voice, and drank eagerly from the cool water. In a few moments he lay dead at the edge of the pool.

The other four brothers waited patiently Nakula’s return. At last Yudhisthira said, “Where can our brother be? Go, Sahadeva, find your brother, and return with a quiver full of water.”

Sahadeva walked off through the forest. Soon he found Nakula lying dead at the edge of the pool. But he was so thirsty that he did not stop, but knelt down at the pool to drink.

The stern Voice spoke: “Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

But Sahadeva had already drunk from the water, and lay dead at the edge of the pool.

Once again the remaining brothers waited patiently. At last Yudhisthira spoke to his brother Arjuna, the mighty archer. “Go, Arjuna,” he said, “find our brothers, and return to us with a quiver full of water.”

Arjuna slung his bow over his shoulder, and with his sword at his side walked to the pool. When he saw his brothers lying dead among the reeds, he fitted an arrow to his bow while his keen eyes pierced the darkness of the forest searching for the enemy who had killed them. Seeing neither human nor wild beast, at last he knelt down at the edge of the pool to drink.

The stern Voice spoke: “Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Prince Arjuna looked about him. “Come out,” he cried, “and fight with me.” He shot arrows in all directions, but the Voice only laughed at him, and repeated its command.

But Arjuna ignored the Voice, knelt and drank, and soon lay dead at the edge of the pool.

Yudhisthira waited patiently, but when Arjuna did not return, the king turned to Bhima. “Go,” he said, “find our brothers, and return with them and a quiver full of water.”

Bhima silently rose, walked to the pool, and found his brothers lying dead. “What evil demon has killed my brothers,” he thought to himself, looking around. But he was so thirsty he knelt to drink.

Again the stern Voice spoke: “Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Bhima had not heard the Voice, and so he lay dead next to his brothers.

Yudhisthira waited for a time, then went himself to find water.

When he came to the pool, he stood for a moment looking at it. He saw clear water shining in the sunlight, lotus flowers floating in the water, and a crane stalking along the edge of the pool. And there were his four brothers lying dead at the edge of the pool.

Even though he was terribly weak and thirsty, he stopped and spoke aloud the name of each of his brothers, and told of the great deeds each had done. He spoke out loud his sorrow for the death of each one.

“This must be the work of some evil spirit,” he thought to himself. “Their bodies show no wounds, nor is there any sign of human footprints. The water is clear and fresh, and I can see no signs that they have been poisoned. But I am so thirsty, I will kneel down to drink.”

As King Yudhisthira knelt down, the Voice took the shape of a Baka, or crane, a gray bird with long legs and a red head. The Baka spoke to him in a stern voice, saying:

“Do not drink, O King, until you have answered my questions.”

“Who are you?” said Yudhisthira boldly. “Tell me what you want.”

“I am not a bird,” said the Baka, “but a Yaksha!” And Yudhisthira saw the vague outlines of a huge being above crane, towering above the lofty trees, glowing like an evening cloud.

“It seems I must obey, and not drink before I answer your questions,” said the king. “Ask me what you will, and I will use what wisdom I have to answer you.”

So the questioning began:

The Yaksha said: “Who makes the Sun rise? Who moves the Sun around the sky? Who makes the Sun set? What is the true nature of the Sun?”

The King replied: “The god Brahma makes the sun rise. The gods and goddesses move the Sun around the sky. The Dharma sets the Sun. Truth is the true nature of the Sun.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is heavier than the earth? What is higher than the heavens? What is faster than the wind? What is there more of than there are blades of grass?”

The King replied: “The love of parents is both heavier than earth and higher than the heavens. A person’s thoughts are faster than the wind. There are more sorrows than there are blades of grass.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is it, that when you cast is aside, makes you lovable? What is it, that when you cast it aside, makes you happy? What is it, that when you cast it aside, makes you wealthy?”

The King replied: “When you cast aside pride, you become lovable. When you cast aside greed, you become happy. When you cast aside desire, you become wealthy.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is the most difficult enemy to conquer? What disease lasts as long as life itself? What sort of person is most noble? What sort of person is most wicked?”

The King replied: “Anger is the most difficult enemy to conquer. Greed is the disease that can last as long as life. The person who desires the well-being of all creatures is most noble. The person who has no mercy is most wicked.”

The questions went on and on, but Yudhisthira was able to answer them all, wisely and well.

At last the Yaksah stopped asking questions, and revealed its true nature: the Yaksha was none other than Yama-Dharma, the god of death, and the father of Yudhisthira.

Yama-Dharma said, “It was I who took on the shape of a deer and stole the wooden blocks so the Brahmin could not light the sacred fire.

“Now you may drink of this fair water, Yudhisthira! And you may choose which of your four brothers shall be returned to life.”

“Let Nakula live,” said Yudhisthira.

“Why not Bhima or Arjuna or Sahadeva?” said Yama-Dharma.

“My brother Nakula is the son of Madri,” said the King, “while Arjuna, Bhima, Sahadeva and I are the sons of Kunthi. If Nakula returns to life, then both my mothers, both Madri and Kunthi, will have a living child. Therefore, let Nakula live.”

Then Yama-Dharma spoke kindly as he faded away. “Truly you are called ‘The Just,” he said. “Noblest of kings and wisest of all persons, for your wisdom and your love and your sense of justice, I shall return all of your brothers to life.”

More riddles — Here are two dozen more of the riddles that Yama-Dharma asked of Yudhisthira:

1. How may a person become secure? — A person becomes secure through courage.

2. How may a person become wise? — A person gains wisdom by living with people who are wise

3. What is best for the Brahmans (those who pursue learning as their life’s work)? — Studying the Vedas, the holy books, is best for the Brahmans.

4. What is best for the Kshathriyas (those who are the warriors and defenders)? Weapons are best for the Kshathriyas.

5. What is best for farmers? — Rain is best for farmers.

6. Who does not close their eyes when sleeping? — Fish do not close their eyes when sleeping.

7. What does not move even after birth? — Eggs do not move even after birth.

8. What does not have a heart? — A stone does not have a heart.

9. What grow as it goes? — A river grows as it goes to the sea.

10. Who is the guest who is welcome to all? — Fire is the guest who is welcome to all.

11. Who travels alone? — The Sun travels alone.

12. Who is born again and again? — The Moon is born again and again.

13. What container can contain everything? — The Earth can contain everything.

14. Out of all things, what is best? — Out of all things, knowledge gained from wise people is best.

15. Out of all blessings, what is best? — Out of all blessings, good health is best.

16. Out of all pleasures, what is best? — Out of all pleasures, being contented is best.

17. Out of all just actions, which is best? — Out of all just actions, non-violence is best.

18. What must a person control in order to never be sad? — A person must control their mind in order to never be sad.

19. What will a person never be sad to leave behind? — A person will never be sad to leave behind anger.

20. What should a person leave behind to become rich? — A person should leave behind desire in order to become rich.

21. What should a person leave behind to be have a happy life? — A person should leave behind selfishness to have a happy life.

22. By what is the world covered? — The world is covered by ignorance.

23. Why doesn’t the world shine brightly? — Bad behavior keeps the world from shining brightly.

24. What is surprising? — It is surprising that we think of ourselves as stable and permanent, when every day we see beings dying.

Illustrations are from the following public domain sources (accessed through the Internet Archive):

Sarus Crane, H. E. Dresser, “A History of the Birds of Europe,” London: 1871-1881.

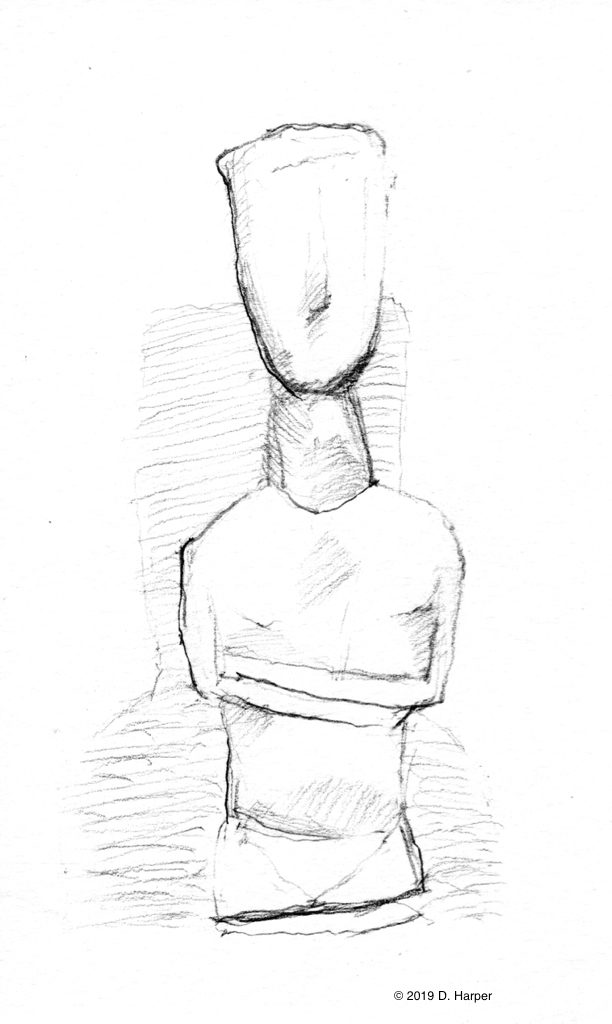

Yudhistira and the crane, Mahabharata, Gorakhpur, India: Geeta Press, n.d.