Part Twoof a history I’m writing, telling the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

The Unitarian Church of Palo Alto Begins, 1905-1910

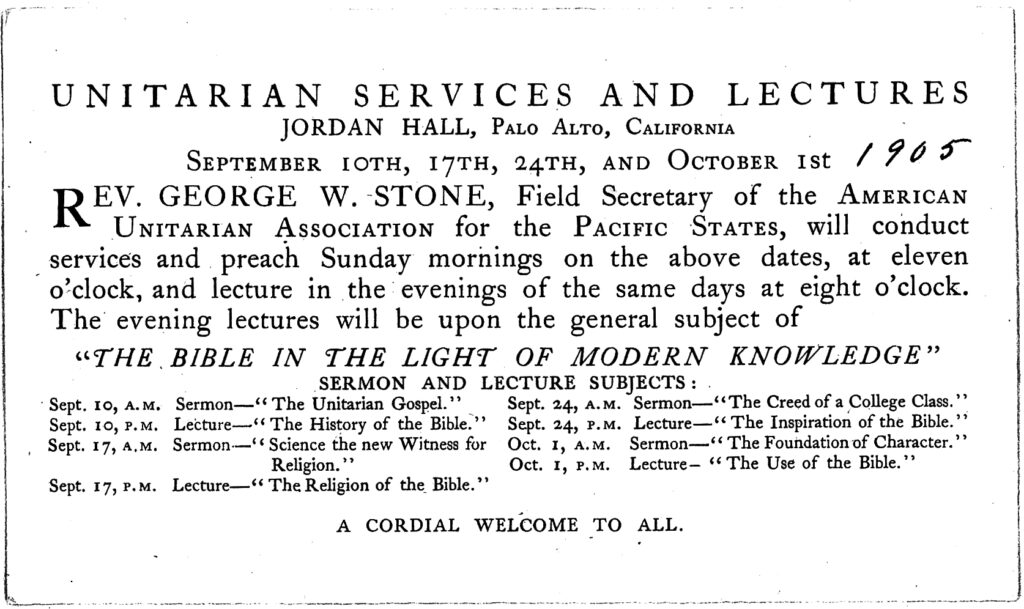

In 1905, Helene and Ewald Flügel invited Rev. George Whitefield Stone, the Field Secretary of the American Unitarian Association for the Pacific States, to come to Palo Alto to christen their children. When Stone arrived in September, 1905, the Flügel children were aged 4, 10, 13, and 15 years old. The family had lived in Palo Alto since 1892; it may be Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes had christened the two eldest children in 1895. In any case, Stone came to Palo Alto, and while there he conducted Unitarian services each Sunday from September 10 through October 8. At the conclusion of the service on October 8, Stone said he was willing to continue with weekly worship services if those assembled showed sufficient interest. Karl Rendtorff made a motion “that a Unitarian Church be formed at once,” giving Stone the authority to appoint a “Provisional Committee” to transact any necessary business until a regular congregational organization could be formed. The motion was seconded by Melville Anderson, and “carried by a rising vote.”

Stone promptly appointed five men and two women to the Provisional Committee: Melville Anderson, John S. Butler, Henry Gray, Agnes Kitchen, Ernest Martin, Fannie Rosebrook, and Karl Rendtorff, who became the Secretary-Treasurer. Melville Anderson, Henry Gray, Ernest Martin, and Karl Rendtorff were all professors at Stanford. John Butler and Fannie Rosebrook had both been on the executive committee of the old Unity Society. Agnes Kitchen was active in civic affairs in Palo Alto, including the Woman’s Club. Once again, women filled leadership positions in the new Unitarian congregation from the very beginning.

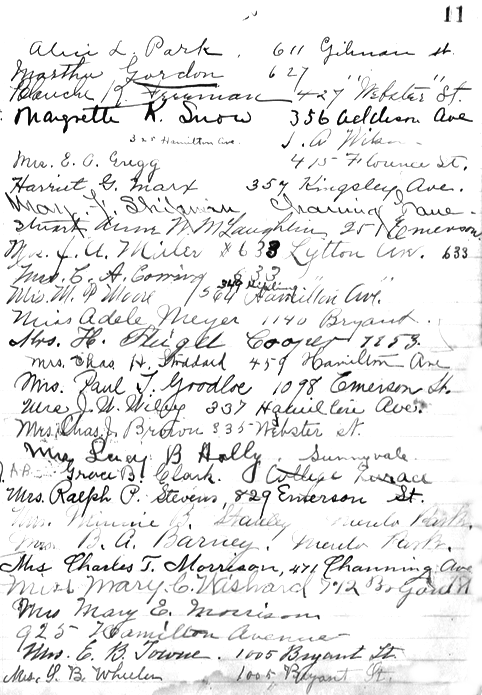

Just two weeks later, on October 23, the women formed their own Unitarian organization. The Women’s Alliance, formally known as the “Branch Alliance of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto,” became a local chapter of the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women. How did the Palo Alto women decide to form their own Branch Alliance so quickly? Perhaps George Stone promoted the idea. The national organization existed to “to quicken the life of our Unitarian churches,” which would have suited Stone’s goal of building a self-sustaining Unitarian church. But it’s equally possible that some of the women had already belonged to a Unitarian women’s group. The National Alliance had roots in several earlier organizations, including the Western Women’s Unitarian Conference, organized in St. Louis in 1881; Emma Rendtorff and her mother Emma Meyer were active Unitarians in St. Louis in that year. Closer to Palo Alto, the women’s organization of the San Francisco Unitarian church, called the Channing Auxiliary had been active in promoting Unitarianism along the entire Pacific Coast ever since it was formed in 1873; perhaps some of the early members of the Palo Alto Alliance had contact with the Channing Auxiliary.

According to the national organization, the general goals of a Branch Alliance were as follows:

“The first duty of each branch is to strengthen the congregation to which it belongs. … Each branch is expected to engage in some form of religious study, not only for the improvement of the members themselves, but to enable them to gain, and to give others, a comprehensive knowledge of Unitarian beliefs. … With this preparation the Alliance undertakes the higher service of joining in the missionary activities of the denomination. … This includes…aiding small and struggling churches, helping to found new ones, supporting ministers at important points, and distributing religious literature among those who need light on religious problems.”

The Palo Alto Branch Alliance carried out all these tasks with dedication and perseverance from its founding in October, 1905, until its final dissolution in October, 1932. The Alliance raised a significant amount of money for the church during its 27 years of existence. Its members engaged in regular “religious study,” and may have been better versed in Unitarianism than many of the men in the church. The Alliance acquired a selection of Unitarian pamphlets and distributed this religious literature both in the church and through the U.S. mails. Alliance women cleaned the buildings, taught in the Sunday school, organized church social events, and met with other Unitarian women to learn from one another. It was the single most important group within the church, and without it the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto could not have existed.

The importance of women leaders in the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto cannot be overemphasized. Although prominent or charismatic men got most of the credit—male ministers like Sydney Snow, or male laypeople like David Starr Jordan and William Herbert Carruth—the Women’s Alliance did much of the critical behind-the-scenes work that allowed the male leaders to stand in the spotlight. And the national network of Unitarian women also provided key financial support to the nascent church: both the Channing Auxiliary in San Francisco and the St. Louis Branch Alliance made significant financial contributions in the first year of the Palo Alto church’s existence.

Collection of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, used by permission

The American Unitarian Association also provided critical financial support to the new church. In fact, the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto could not have afforded to pay its ministers without the financial support from the denomination. The lay leaders of the new church aspired to become financially independent in the future, especially as it became clear that money from the denomination entailed some loss of local control, but for the moment they were happy to receive whatever financial assistance they could get.

In the late autumn of 1905 and through the winter, the prospects for the new church looked bright. More than a dozen people signed the church covenant, “In the love of the truth, and the ‘Spirit of Jesus,’ we unite for the worship of God and the service of man.” Equally importantly, some forty Unitarians contributed varying sums of money to purchase a building lot on which to erect a church. A newly-elected Board of Trustees were able to obtain the services of respected Bay Area architect Bernard Maybeck, who was himself a Unitarian, to design their new church building. And the American Unitarian Association found a minister to send to Palo Alto, one Sydney Bruce Snow, a former newspaper reporter who was about to graduate from Harvard Divinity School in the spring of 1906.

Then on April 18, 1906, the great earthquake temporarily halted the church’s forward progress. Guido Marx, professor at Stanford University and a Unitarian, remembered the earthquake:

“Gertrude [his wife] and I were rudely awakened by the shaking of the house and the accompanying rumble, roar, and crash. ‘What is it?’ said she. ‘It’s an earthquake—and it’s a bad one,’ I replied. ‘What shall we do?”Stay right here. This little house will last as long as anything.’ I knew the sturdy construction of our bungalow…but in my heart I felt that nothing could survive such a vicious shaking—that this was the end for us. It was like a terrier shaking a rat.” [Quoted in Sandstone and Tile, vol. 30, no. 1, winter, 2006 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Historical Society, 2006), p. 3.]

The damage in Palo Alto was not as bad as it was in San Francisco, but it was still extensive. Palo Alto Unitarians had to turn their attention to relief work, so they had little time to think about their new congregation. There could be no progress on the new building in any case, since Maybeck’s plans for the new church building burned in the San Francisco fires following the earthquake.

Sydney and Margrette Snow’s arrival in Palo Alto in the autumn of 1906 served as a coalescing force for the new church. The congregation ordained Snow on October 14, 1906, renting space for the ceremony in Jordan’s Hall on University Ave. in Palo Alto. Sydney and Margrette formally joined the church as members that same month, and Margrette also joined the Women’s Alliance. In his first year as minister, Snow had to officiate at the funeral of Agnes Kitchen, a member of the Board of Trustees. This was confirmation that forming a new church was the right thing to do. The Palo Alto Unitarians had wanted a minister who could officiate at rites of passage—think of George Stone christening of the Flügel children—and the untimely death of Agnes Kitchen helped justify the work and expense that was going into the new congregation. Having a church with a minister was already much better than the old lay-led Unity Society.

Another reason the Palo Alto Unitarians formed their church was to provide religious education for their children. The church organized almost right away, and Emma Rendtorff became the Superintendent. In the 1905-1906 school year, nine children enrolled in the Sunday school. We can make a good guess of who those nine children were by looking at children from church families who were about the right age. These include Felix Flügel, who turned 13 in 1905; Barbara Alderton, who turned 12; Stephanie Marx (child of Charles and Harriet), 12; Ewald Flügel, Jr., 10; Henry Alderton, Jr., 9; Eleanor Marx (child of Guido and Gertrude Marx), 8; Anna Franklin, 7; Alberta Marx (child of Charles and Harriet Marx), 5; and Guido van Dusen Marx (child of Guido and Gertrude Marx), 5 years old.

Enrollment in the Sunday school increased to 12 children the following year, and then to 17 children in 1907-1908. Adele Meyer, Emma Rendtorff’s sister, took over as Superintendent of the Sunday school in 1907-1908, which is also probably the year that Emma’s daughter Gertrude was finally old enough to enroll.

Bernard Maybeck drew up a new set of plans for the church building, over the summer of 1906. Funding for the building came from the American Unitarian Association, and from the national Young People’s Religious Union organization, which hoped to promote Unitarianism in yet another college town. Frances Hackley of Tarrytown, N.Y., a Unitarian philanthropist, also donated money. Because of the rebuilding efforts following the earthquake, construction prices had risen. but luckily “the lowest bid was just low enough,” and construction began.

While their new building was under construction, the church continued to meet in rented space in Jordan’s Hall in Palo Alto. On Sundays, the Sunday school met first, at ten o’clock, with the worship service at eleven. And in late November, 80 people came together for the first anniversary dinner. Finally, in March, 1907, their new building was ready for them. A lengthy description of the building appeared in the Palo Alto Times on March 17, 1907:

“The new church, which has attracted considerable attention during its construction, is somewhat unusual in design. It is the work of Mr. B. R. Maybeck, of the firm of Maybeck & White, who has erected several of the buildings connected with the University of California and other semi-public structures in Berkeley. The church in Palo Alto is noteworthy in the use of rough, less expensive forms of material for a permanent building, designed to have all the atmosphere of a church. The only materials used in the interior finish are redwood boards and battens, common redwood shakes, rough heavy timbers, which rather more than carry the weight of the roof, and cement plaster like that used for the outside of buildings, forming a deep chancel arch as high as the roof. The timbers, whose rough surfaces have been left unplaned, are stained with an old-fashioned logwood dye, such as our grandmothers used in their dye-pots, giving a deep color, almost black. The shakes were dipped in an acid solution before they were put on the ceiling, and have turned gray, not unlike the stone-gray of the cement. The surfaced redwood of the walls and pews is being finished by a Japanese painter who understands the treatment of this fickle wood, and it will take on a soft gray color to harmonize with the shakes and plaster.

“The windows of the church, which are set high, will have small leaded panes of a light amber tone, and the lanterns for illumination at night will give as nearly as possible the same light. The color scheme is completed by the hangings and upholstering in the chancel, a soft plush velour, rose pink in shade. The pulpit and a high hooded chair are to be covered with this material, and a curtain will hang behind the chair across the whole width of the chancel and down the sides to the arch. It is intended later to cover the rail of the choir loft, and the swinging doors from the vestibule to the church with the same material.

“The aisles of the church are along the sides, the pews running solid through between two rows of posts, which form the main support of the building. From these posts and from the posts set in the side walls run heavy beams clear to the roof tree. The roof spaces between the beams are covered with shakes down to the walls, where the boards and battens begin. The chancel arch is the denominating feature of the interior. It is, as already stated, as high as the roof, and is massive like the rest of the structure. The pulpit stands directly under the center of the arch, three or four steps higher than the lower level of the church floor.

“On each side of the chancel is a room, the larger one in the tower on Cowper Street being a parlor, and the smaller, on the other side, a study for the minister. The parlor is very high and is finished similarly to the church. The building is set very close to the street, its front steps coming almost to the sidewalk on Channing Avenue, and the tower lying only a few feet from Cowper Street. This position was made necessary by the size of the lot, but after construction had begun the congregation bought an additional fifty feet on Channing Avenue, making a frontage of 125 feet, and 100 feet on Cowper Street. This gives room for enlargement and development. The church with the gradual slope of its roof, and the three dormers on each side, is low in effect. The tower at the rear, however, breaks the skyline with its turrets. The vestibule at the front has a lower, flat roof, whose beams project beyond the wall, and with cross-lattice work form support for vines. It is planned to have the whole church overrun with vines, for like all such buildings, it is not complete without the setting which only time and the growth of shrubs and vines can give.”

Collection of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, used by permission

The congregation chose to use the hymnal Hymns of the Ages (1904), edited by Louisa Putnam Loring. This hymnal was a selection of hymns from the University Hymn Book, an 1895 hymnal compiled by Unitarians at Harvard University. However, according to Unitarian historian Henry Wilder Foote, Hymns of the Ages “represented a rather limited and individualistic point of view and did not prove adaptable to general use.” A few years later, during Clarence Reed’s tenure as minister, the church would replace this hymnal with the American Unitarian Association’s new Hymn and Tune Book (1911).

By the time of its third anniversary, the new congregation was still small, but growing. On November 10, 1908, “between fifty and sixty people” attended the third anniversary celebration which included dinner, after-dinner speeches, and dancing. Because the church didn’t have a social hall yet, the celebration again took place in Jordan’s Hall. The church could look back on three years of steady accomplishment: they had purchased a building lot, called a minister, survived the great earthquake, and built a building. And they looked forward to further progress, for at the dinner the Women’s Alliance announced a initial contribution of $100 ($2900 in 2020 dollars) so they could build a much-needed social hall.

Five months later, on April 11, 1909, Sydney Snow announced his resignation. He had been offered the position as minister of the Unitarian church in Concord, N.H., a larger congregation with a larger salary. The lay leaders of the Palo Alto church presented Snow with an expression of their appreciation done in beautiful calligraphy, which said in part:

“You have won your way into our hearts; you have brought us many messages of inspiration, of comfort, and of steadfastness; you have never failed to give us the sympathy, the friendship, and the light which we have needed. … Though our hearts are torn with personal sorrow at your going, though we would have you ever with us as your guide and friend, yet we do not falter or despair… Go from us, then, to be to others all you have been to us.…”

During the rest of its existence, the members of the congregation were never able to retain the ministers they liked best. They were always too small, and they never had enough money to pay an attractive salary to keep a minister for more than a few years.