Part One of a history I’m writing, which tells the story of Unitarians in Palo Alto from the founding of the town in 1891 up to the dissolution of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1934. Rather than telling history as the story of a succession of (mostly male) ministers, my focus is on the lay people who made up the congregation. If you want the footnotes, you’ll have to wait until the print version of this history comes out in the spring of 2022.

The first Unitarian and Universalists in Palo Alto, 1891-1895

Unitarianism and Universalism arrived in Palo Alto before there was a congregation. Some of the first residents who arrived in Palo Alto in 1891, the year Stanford University opened, were already Unitarians and Universalists.

Emma Meyer Rendtorff began studying at Stanford University in 1894, eight months before Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes, a Universalist and Unitarian minister, preached the first Unitarian Universalist sermon in Palo Alto, at Stanford’s Memorial Church. Emma’s parents had been Unitarians, and as a girl she had attended Sunday school the Church of the Unity, a Unitarian church in St. Louis, Missouri. She was a lifelong Unitarian, and would play a key role when the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto was organized in 1905.

David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford, grew up in a Universalist family. As a young adult he briefly joined a Congregational church. While president of Stanford he disavowed any denominational affiliation, although he often spoke in Unitarian churches and at Unitarian gatherings. Whether or not he would have called himself a Unitarian or Universalist when he arrived in Palo Alto, he was often perceived as a Unitarian and often provided financial and moral support to the Palo Alto Unitarians. And when he retired from Stanford, he finally did join the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

Luna, Minnie, and Leander Hoskins were probably Unitarians before arriving in Palo Alto. Minnie moved in Palo Alto in 1892 when her husband Leander became a Stanford professor, and Luna had joined them in Palo Alto soon after. Luna and Minnie Hoskins were recognized as delegates by the Committee on Credentials of the Pacific Unitarian Conference at San Jose on May 1-4, 1895, a few days before Eliza Tupper Wilkes arrived in Palo Alto. Since they knew about Unitarianism before Eliza Tupper Wilkes arrived, she couldn’t have been the one to introduce them to Unitarianism, so it seems likely they had been Unitarians when they came to Palo Alto.

Eleanor Brooks Pearson, who came to Palo Alto in 1891 from South Sudbury, Massachusetts, may have been a Unitarian before she arrived in Palo Alto; her childhood home in South Sudbury would have been close to the Unitarian church in Sudbury Center, she was one of the organizers of the Unity Society in 1895, and she later married a Unitarian, Frederic Bartlett Huntington. Some sources hint that there were others who were Unitarians or Universalists before arriving in Palo Alto, but so far it has proved impossible to name them.

The Unity Society, 1895-1897

In November, 1892, the very first issue of the Pacific Unitarian, a periodical devoted to promoting liberal religion up and down the West Coast, declared that a Unitarian church should be organized in Palo Alto:

“The University town of Palo Alto is growing fast. Never was there a field that offered more in the way of influence and education than this. A [building] lot for a church ought to be secured at once, and the preliminary steps taken towards the organization of a Unitarian Society.”

Organizing churches in college towns had been a standard missionary strategy for the American Unitarian Association (AUA) since the denomination had funded a Unitarian church in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1865. These “college missions” were seen as “one of the most effective ways of extending Unitarianism,” and many of them resulted in strong Unitarian congregations.

But where would the Palo Alto Unitarians find someone who had the time and the skills to organize a Unitarian church? The Unitarian church in San Jose was the one nearest to Palo Alto, and a minister of that church could have been such a person. In fact, in early 1893, the two ministers of the San Jose church, Revs. Nahum. A. Haskell and J. H. Garnett, organized two new Unitarian congregations in Los Gatos and Santa Clara. But they didn’t come to Palo Alto. Support for a new Palo Alto congregation would have to come from someone else.

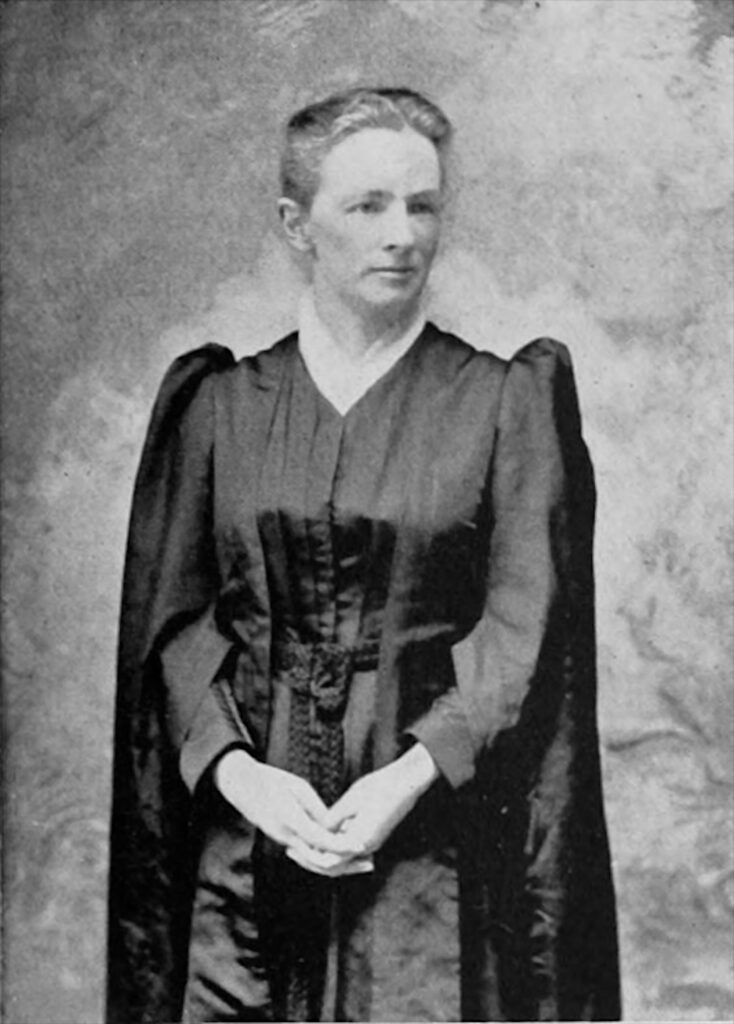

Coincidentally, around 1890, Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes, an experienced Universalist minister who had founded a number of Universalist and Unitarian churches in Iowa and Dakota Territory, began spending winters in California on account of her health. Soon she was hired as the assistant minister in the Oakland Unitarian church. The Panic of 1893 resulted in an economic depression, and by 1894 Oakland had to reduce her position to part-time. The Pacific Unitarian Conference then hired Wilkes on a part-time basis to organize new congregations in California.

Wilkes attended the Pacific Unitarian Conference in San Jose, May 1-4, 1895, as did Palo Altans Minnie and Luna Hoskins. There weren’t many people at the San Jose gathering and surely the three women encountered one another. And Wilkes was already headed to Palo Alto; that Sunday, May 5, the day after the conference ended, she became the first woman to preach at the Memorial Church of Stanford University. It seems likely that David Starr Jordan, who had connections in the Pacific Unitarian Conference, encouraged Minnie and Luna Hoskins to attend the San Jose gathering, and that he arranged for Wilkes to preach at Stanford; if so, Jordan could be counted as one of the organizers of Palo Alto Unitarianism.

By the autumn of 1895, the Women’s Unitarian Conference was paying much of Wilkes’s salary, and they specifically authorized her to “preach in Palo Alto, assist in Berkeley and elsewhere.” In November, 1895, Wilkes began conducting Unitarian services at Parkinson’s Hall in Palo Alto, and continued to do so into the next year. Professors, students, and other residents of Palo Alto began attending these services, and on January 12, 1896, John S. Butler hosted a meeting at his house to formally organize a new congregation.

The thirty people present organized the Unity Society of Palo Alto for “the promotion of moral earnestness, and of freedom, fellowship, and character in religion, and which shall impose no restriction on individual belief.” A “Unity Society” was the Unitarian term in those days for a lay-led congregation, and no one expected Wilkes to continue as the minister in Palo Alto. Prof. Leander Hoskins was elected president of the new society; Dr. William Adams, a physician, was elected secretary; and John S. Butler, a wealthy man who had retired to Palo Alto, was elected treasurer. Two others were elected to the “committee on executive and finance”: William F. Pluns, a German immigrant and builder, and Fannie Rosebrook. It’s noteworthy that the first board of the first Unitarian society in Palo Alto included a woman.

A Sunday school was part of the new congregation from the start. The Sunday school committee included Minnie Hoskins; Eleanor Brooks Pearson, a teacher at Castilleja Hall; and Anna Zschokke. Anna Zschokke was a Bavarian immigrant with a deep concern for education, and she has been called “the mother of the Palo Alto schools.”

Unity Society services were held in the parlors of the Palo Alto Hotel at 2:30 on Sunday afternoons. Sunday school began at 2:45. Music for the services was provided by a quartet. Sunday speakers included Prof. Melville B. Anderson who gave a talk on poetry and religion and read “extracts from different poets in illustration.”

How was the new congregation perceived by the rest of Palo Alto? An article in the local newspaper shows that some of the same jokes told about Unitarian Universalists today were also current in 1896:

“Ecclesiastical babies like human babies have all the funny things told about them. Our infant Unitarian Church, or Unity Society as they call it, therefore must expect to come in for their share.

“A San Francisco daily recently noticed their beginning under the conspicuous headlines ‘An organization that does not believe in anything in particular founded at Palo Alto.’

“Another good one is told on them when they met for service in the hotel parlor two Sabbaths ago. After the little company sang some hymns, and read some prayers, the Professor who was to address them began his talk upon the Relation of Poetry and Religion. In the course of his remarks he had occasion to refer to the Bible. He looked for one in the pulpit and under the pulpit but there was none there. Then he appealed to some one in the congregation to lend him theirs, but the Law and the Gospel was not in the possession of them. Finally the good landlady went up stairs and succeeded in finding one in the room of some benighted godless student, and as she placed it in the hands of the Professor he dryly remarked, ‘I knew this was a very advanced society, but I thought you still clung to the Old Book.'”

At the time of the April, 1896, meeting of the Pacific Unitarian Conference, Wilkes was still providing some support to the Palo Alto congregation, but she was only interested in starting new congregations, not keeping them going once they were started. Rev. Carl Wendte, the director of the Pacific Coast Unitarians, expressed his opinion that “the two San Francisco churches should make this Palo Alto movement their peculiar care, aiding it by ministerial service, money contributions, and general supervision and help.”

If the San Francisco churches did provide support, it was not enough to keep the Palo Alto Unity Society going. The tiny congregation continued in existence for another eleven months. It was listed in the Pacific Unitarian in the March, 1897, issue, but after that it disappears from the written record.

Interregnum, 1897-1905

The Unity Society was gone, but there were still Unitarians and Universalists in Palo Alto. When the California Sunday School Association took a census of the town in November, 1898, parents reported 21 school-aged children who were Unitarians, and five who were Universalists. Some of these Unitarian and Universalist children may have attended Sunday schools in other churches, but their parents would have longed for a liberal church in Palo Alto.

On Sunday, March 25, 1900, Rev. B. Fay Mills, minister of the Oakland Unitarian church, led a Unitarian service in Palo Alto, preaching on the topic of “the claims of liberal religion upon the modern world.” Organizers informed a local newspaper:

“A series of religious services will be held in Palo Alto every Sunday afternoon at Fraternity Hall, under the auspices of the Unitarian church. Cards pledging support are circulating that the members recognize the need of a religious organization in Palo Alto that shall represent the thought of our age, and leaving unquestioned the theological belief of its members, shall make its bond of Unity the Fellowships of the Spirit, and the Service of Man.”

The next Sunday, April 1, Rev. Nahum A. Haskell, minister of the San Jose Unitarian church, preached to the Palo Alto Unitarians. After forming Unitarian congregations in Los Gatos and Santa Clara in the 1890s, Haskell had turned his attention to Palo Alto. Unfortunately, on April 10, 1900, the annual meeting of the San Jose church asked for Haskell’s resignation, feeling he was responsible for their declining membership. Haskell managed to remain as minister of the San Jose for two more years, but after that vote he was no longer able to help form a new church in Palo Alto.

On May 31, Haskell officiated at a double wedding in Palo Alto for Alice and Florence Emerson, Stanford students and daughters of a wealthy lumber tycoon. Their wedding was the last formal Unitarian activity in Palo Alto until 1905.