Many of the trees are still green here in West Concord, Massachusetts, but others have taken on brilliant fall color — like these trees behind my dad’s condo:

Category: Places

Religion in the public square

In the United States, all too often the phrase “religion in the public square” means someone accosting you and telling you that you should join their religion; so the meaning of the phrase becomes, “our religion is right and yours is wrong.” Or that same phrase can be used pejoratively to imply that all religious practice shouldb e kept out of public view; so the meaning of the phrase becomes, “all religion is wrong.” Either way, someone is imposing their own views on the rest of a democratic society.

But if ours is a truly multicultural democracy, we should allow space in the public square for a variety of worldviews, without letting any one worldview dominance over the others. This becomes a delicate balancing act. Literal or metaphorical shouting matches between religious worldviews don’t promote tolerance; mind you, sometimes you have to get into shouting matches to preserve the openness of the public square, as when we have to fight to limit Christmas displays on public property, but no one imagines that these shouting matches increase tolerance. So given that public religious expression is a delicate balancing act, what does it look like when you have an appropriate expression of a religious worldview in the public square?

Today I saw such an expression of a religious worldview in the public square, and it looked like a rented flatbed trailer with a sukkah built on top of it. The trailer was parked in front of the Jewish Learning Institute of San Francisco (JLISF), on Lombard Ave. right off busy Columbus Ave in the North Beach neighborhood. Carol and I walked by just as some people from JLISF were cleaning up from lunch. They were polite and friendly, and ready to explain that they were celebrating Sukkot, and what a sukkah was, and so on.

This is a good display of religion in the public square: present, but not intrusive; with friendly people who are ready to explain, but not berate.

(Posted the next day, and backdated.)

De Young Museum, San Francisco

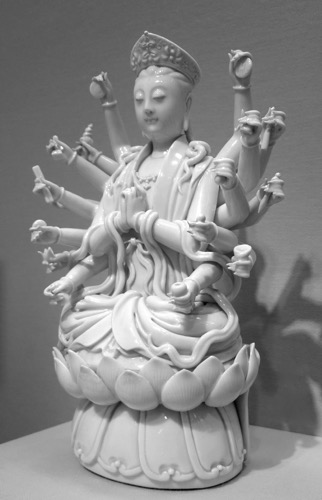

Doumu

Above: porcelain image of the Taoist deity Toumu [Doumu], made in Fujian province in the 18th century, now in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (catalog no. B60P1362).

“The Dipper Mother [Doumu] is a star deity and a Daoist adoption of the Tantric deity Marici, a personification of light and dawn. As a savior and healer, she is invoked through visualizations that unite the adept with cosmic light and ‘oneness with cosmic principles’ (75-76). As the cosmic mother of the nine star-gods of the dipper, she is a nurturer and instructress, but the Dipper Mother also maintains her own salvific powers and authority.”

From a book review by Sara Elaine Neswald of McGill University on the Daoist Studies Web site (2 Dec. 2004), of the book Women in Daoism by Catherine Despeux and Livia Kohn (Cambridge, Mass.: Three Pines Press, 2003).

———

Update: August 12, 2019: Entry on Doumu in E. T. C. Werner, Myths and Legends of China (London: George G. Harrap & Co., 1922), pp. 144-145:

Goddess of the North Star

Tou Mu, the Bushel Mother, or Goddess of the North Star, worshipped by both Buddhists and Taoists, is the Indian Maritchi, and was made a stellar divinity by the Taoists. She is said to have been the mother of the nine Jen Huang or Human Sovereigns of fabulous antiquity, who succeeded the lines of Celestial and Terrestrial Sovereigns. She occupies in the Taoist religion the same relative position as Kuan Yin, who may be said to be the heart of Buddhism. Having attained to a profound knowledge of celestial mysteries, she shone with heavenly light, could cross the seas, and pass from the sun to the moon. She also had a kind heart for the sufferings of humanity. The King of Chou Yu, in the north, married her on hearing of her many virtues. They had nine sons. Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun came to earth to invite her, her husband, and nine sons to enjoy the delights of Heaven. He placed her in the palace Tou Shu, the Pivot of the Pole, because all the other stars revolve round it, and gave her the title of Queen of the Doctrine of Primitive Heaven. Her nine sons have their palaces in the neighbouring stars.

Tou Mu wears the Buddhist crown, is seated on a lotus throne, has three eyes, eighteen arms, and holds various precious objects in her numerous hands, such as a bow, spear, sword, flag, dragon’s head, pagoda, five chariots, sun’s disk, moon’s disk, etc. She has control of the books of life and death, and all who wish to prolong their days worship at her shrine. Her devotees abstain from animal food on the third and twenty-seventh day of every month.

Of her sons, two are the Northern and Southern Bushels; the latter, dressed in red, rules birth; the former, in white, rules death. “A young Esau once found them on the South Mountain, under a tree, playing chess, and by an offer of venison his lease of life was extended from nineteen to ninety-nine years.”

Chinese proverb

No image-maker worships the Gods. He knows what they are made of.

trans. Herbert Giles, Gems of Chinese Literature, p. 245, from a collection of Chinese proverbs.

Summer rain

It has been a strange year here in the Bay area. January, which is supposed to be a cold, wet month, was warm and dry.

And now it is in August, when it never rains. So when I heard a pattering on the roof over my office, I thought: Gee there must be a lot of squirrels scampering around on the roof. But it wasn’t squirrels, it was a passing rain shower.

I went outside and stood in the rain, just to remember what it feels like and to smell the smell of dry earth when it gets moistened, and when the shower was over I went back inside and got back to work.

When it rained again, I had grown blase, and just stayed working at my desk.

But when a third rain shower passed through, that felt freakish.

Winnemucca, Nev., to San Mateo, Calif.

“At the border of the [Great American] Desert,” said Mark Twain, “lies Carson Lake, or The ‘Sink’ of the Carson, a shallow, melancholy sheet of water some eighty or a hundred miles in circumference. Carson River empties into it and is lost — sinks mysteriously into the earth and never appears in the light of the sun again — for the lake has no outlet whatever.” Although I had no interest in walking forty miles across the Great American Desert, without water, as Mark Twain had to do when he was taking the stage coach to Carson City, Nevada, I was interested in seeing the Carson Sink, so I left the interstate highway and drove down U.S. 95. There was no water in the Carson Sink when I drove through, just thousands of acres of bleak desolate salt-encrusted, dried-up mud. The Bonneville salt flats west of Great Salt Lake in Utah are pristine white and shine in the sun, and look sublimely beautiful; but the Carson Sink looks like dirty snow, with more dirt than snow, and looks merely grim.

South of the Carson Sink, the land rose, and grew greener and greener, and there were ranches on either side of the highway, and then I was in Fallon, Nevada, the self-proclaimed “Oasis of Nevada.” I turned east on Nevada Route 116, drove some ten miles through hay fields and ranch lands, passed through the little hamlet of Stillwater, and then out into the 77,000 acre Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge. East of Stillwater, the land grew steadily drier and less hospitable, and it seemed like the only vegetation was clumps of black greasewood (Sarcobatus spp.).

When I went around a bend in the road and suddenly saw open water, I thought at first that I was seeing those heat mirages so common in the Nevada desert. But no, it really was open water, surrounded by tule rushes and cattails.

The Stillwater marshes provide breeding grounds for many birds, and I saw juveniles of several species, including American Coots, Eared Grebes, Pie-billed Grebes, Ruddy Ducks, and various kinds of swallows. I saw Great Blue Herons, Loggerhead Shrikes, Snowy Egrets, Virgina Rails, White Pelicans — and watching huge White Pelicans glide in graceful formation against the backdrop of distant rugged desert mountains was a sight worth seeing. There were other animals in and around the marsh, too — lizards, and some hidden animal, probably a muskrat, that moved noisily among the rushes just at water level about five feet from where I stood, and and half a dozen jackrabbits.

Mark Twain calls this animal a jackass rabbit: “He is well named. He is just like any other rabbit, except that he is from one third to twice as large, has longer legs in proportion to his size, and has the most preposterous ears that ever were mounted on any creature but a jackass.” One of the jackass rabbits I saw started from cover when I got too close, stopped when i froze and stared at me with big black and yellow pop-eyes, let me take a photograph of it, then started suddenly and bounded away and lost himself among the clumps of greasewood.

When I got to Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, the sky was overcast, and the temperature was about 85 degrees — a very pleasant temperature in the dry desert air — but slowly the sun came out and the temperature climbed up to 97 degrees, and there wasn’t any shade to speak of, and I decided it was time to move on. When I sat in the car, almost instantly my back grew wet with sweat; it had been so dry that my sweat dried almost instantly as long as the air could get to me, but once the air was blocked off it soaked my shirt.

From North Dakota to central Nevada the highways are lightly traveled and there were many times when I couldn’t see another vehicle in front of me or behind me. But from Reno to the Bay Area, the highways are heavily traveled, and they wind and twist and go up and down abruptly, and I had to dodge the occasional crazed driver (all of whom seemed to have a California license plate) who thought it great sport to suddenly change lanes and dodge in front of me and slow down and speed up with no apparent rhyme or reason. Driving was no longer enjoyable, and I settled down to suffer.

From Maine to California, I had periodically been monitoring 29.600 MHz, the amateur radio national calling frequency for FM simplex, and in all those miles and hours had heard nothing but static. The driving required too much of my attention to want to try to listen to an audiobook, so I turned on the little 10-meter band radio and started listening to static. Just east of Sacramento, I realized I was hearing someone giving a call sign with a Hawai’i prefix. I replied, he heard me, and I wound up talking to Norm, who lives on the Big Island, some 2,450 miles from Sacramento. Traffic got bad so I had to end the contact — and of course by the time traffic got more reasonable, ten miles west of Sacramento, I could no longer hear Norm, and there was nothing but static once again.

And here I am, back home once more. I like the fact that I don’t have to worry about driving six or seven hours a day any more. I like seeing Carol again. I’m even looking forward to going back to work on Sunday. But I wish vacation weren’t over.

Pocatello, Idaho, to Winnemucca, Nev.

The day did not start well. I awakened in the midst of a dream about work — you know a vacation is almost over when thoughts of your job work their way into your dreams. And then when I got to the Minidoka National Wildlife Refuge in mid-morning, I found out that I would need a high-clearance vehicle to access the interesting parts of the refuge. So I drove on towards Winnemucca, trusting to luck.

I followed a sign pointing to Shoshone Falls, and pulled over at the Hansen Bridge overlook. The view from the little parking area was dramatic — the bridge crossing a nine hundred foot wide canyon some four hundred feet above the Snake River. I thought that maybe if I kept walking on the adjacent Bureau of Land Management property, the view up the canyon towards the bridge would be even more dramatic, and it was. I climbed down and out on the volcanic rock of the canyon rim and watched Swainson’s Hawks and Red-tailed Hawks circling far below me, startling flocks of Rock Pigeons roosting in holes in the cliffs as they circled past.

Then I looked down the canyon, and that view was also dramatic: the canyon became broader, and the river divided into several streams, flowing around islands in the middle of which were buttes, the green of the riparian corridor making a strong contrast with the harsh black cliffs of the canyon walls. I walked around for three quarters of an hour, entranced by the view down into the canyon.

At last I drove on to Shoshone Falls. There isn’t enough water in the summer to make the falls truly dramatic, but they were dramatic enough. I was almost more interested in watching the tourists watch the falls, than in watching the falls themselves. I thought about walking up the trail to where Evel Kneivel jumped his motorcycle across the canyon, but instead drove up to Dierke’s Lake, which lies in a large flat bench partway down the canyon. The swimming area was swarming with people, including lots of children; it was a friendly, homey scene. I walked up past the swimming area and wound up talking with a man from San Jose who was taking his daughter to tour colleges.

From there, I drove on, stopping briefly in Jackpot, Nevada, where I chatted with the cashier at the grocery store where I bought my lunch-time caffeine; she said Jackpot was the kind of small town where you knew everyone, though she admitted that winters could be kind of long. I ate my lunch at a highway rest area by the side of a stream. Of the three picnic tables in the rest area, two were occupied by single men who appeared to have a lot of possessions with them; one of them had a friendly chat with the workers who stopped to empty the trash cans and restock toilet paper at the pit toilets. I assumed these two men lived in or around that remote rest area.

In Wells, Nevada, I stopped at the Emigrant Trail Center, and talked with the volunteer who was staffing it today. He had grown up in Wells, which began as a railroad town — his parents worked for the railroad — and when the railroad reduced its operations in the late 1960s, jobs shifted to supporting the new interstate highway that came through town. The ranchers in the area, he said, also contributed a good deal to the local economy. After the earthquake of 2008, which destroyed many of the old historic brick buildings in the town, a vein of gold was discovered, and plans are now being made to mine that vein — which, he hoped, would add more jobs to the local economy. On my way out of town, I stopped to take a picture of the Community Presbyterian Church, which — so said my friend who grew up in Wells — had stood for more than a century, pretty much unchanged.

Only one more day to vacation. I’m looking forward to getting back to see Carol. I’m even looking forward to getting back to work — but even so I wish this trip were not going to be over so soon.

Big Timber, Mont., to Pocatello, Idaho

Every once in a while on a long trip you have a day where nothing goes wrong. That happened today. In fact, today was as close to perfect as I’ve gotten on any cross-country trip. I got up on time, and got on the road on time. The drive was easy, with little traffic and no delays. I arrived at Camas National Wildlife Refuge at four o’clock, with at least four hours to spend there.

The refuge consists of over ten thousand acres of varied habitat — open water, marsh, seasonally dry ponds, uplands with bunch grass and sage brush — along Camas Creek. The refuge provides habitat protection for breeding and migrating birds, but hunting and agriculture are also allowed in parts of the refuge.

The weather was perfect, with a temperature of 79 degrees, dry air, light variable breezes, and perfectly clear skies. Almost as soon as I pulled into the parking lot near the refuge headquarters, I flushed a Common Nighthawk from where it was roosting in a tree, and with the sight of it circling around over me calling with a plaintive “peent, peent,” I found myself detached from any thought of workaday affairs. And it got better from there. When you come across inviting green marshlands with large areas of open water in what is close to being a desert landscape, with just over ten inches of precipitation a year, it is an amazing and refreshing sight.

The marshlands were teeming with birds. Admittedly, most of them kept far away from me, and I would have seen more birds if I had had a scope. But the light was excellent, and I could make out many of the birds I saw, even from a distance. I saw a good number of birds that had hatched this year. I saw two Trumpeter Swans accompanied a cygnet, a great many Mallards with ducklings, and lots of American Coots with their young — these three species are captured in the photo below, about as they appeared through my binoculars — as well as many other juvenile birds.

The refuge staff manage the water levels in the pools to maximize food sources, and several of the ponds had been allowed to dry out. These dry ponds looked stark and lifeless at first.

But a closer look at one of them revealed five Pronghorn Antelope — four adults and one juvenile — who were watching me cautiously. I stood watching them watching me, and as I did so a car drove by without even slowing down. A little boy looked at me through the rear window, and I wanted to tell him to tell his parents to turn around and come back and look — but then I got distracted by two juvenile Northern Harriers flying low over the dry grass.

If there was a disappointment in an otherwise perfect day, it was that I didn’t see any Sage Grouse, even though I spent half an hour walking along a trail in the upland habitat near dusk. These uplands hardly merit the name based on elevation, for they are only about ten feet above the level of the marshlands. But that ten feet is enough: the soil is dry gravel, and the vegetation is dominated by short bunch grass — dried a crisp brown in late July — and sagebrush. But I was more than compensated by this disappointment a little later. While I was sitting eating my picnic dinner, with the sun about to set behind the distant mountains, two Swainson’s Hawks tried to roost in nearby trees, only to be repeatedly attacked out by brave Western Kingbirds, and after ten minutes finally driven away, screaming loudly. It was a dramatic conclusion to the day.

I suppose if you are not all that interested in birds, this may not sound like an almost perfect day. Really, though, looking for and identifying birds wasn’t the point. I think we human beings are meant to be outdoors as much as possible, and we are meant to be interacting with other living things as much as possible; evolution has shaped us to this end. Computers and automobiles and toilets and hospitals have made our lives easier and longer and more comfortable, but not necessarily better and more soul-satisfying.

Posted a day late due to poor Internet connection.

Dickinson, N.D., to Big Timber, Mont.

The wind storm from yesterday continued unabated. The National Weather Service warned of sustained winds of twenty to thirty miles per hour, and gusts up to sixty miles per hour. It was an unpleasant drive from Dickinson to Theodore Roosevelt National Park, and I was glad to park the car at the trailhead for the Paddock Trail. As soon as I parked the car, I realized that I was right next to a Prairie Dog town; thirty feet from the car, a Prairie Dog sat feeding at the entrance to a hole, warily keeping an eye on me.

As i looked around me, I saw more and more Prairie Dog holes, lighter-colored mounds of earth dotting the close-cropped vegetation. The mounds started near the edge of a creek and extended up a gently sloping plain to the foot of a butte.

I estimated that the town covered an area of several acres. I walked up the Paddock Trail to the end of the town. Wherever I walked, a Prairie Dog would give a shrill alarm call, poised at the opening of a hole, ready to dart down inside when I got too close. I saw a pair of Mountain Bluebirds and an immature American Robin hopping around in between the holes; perhaps they were feeding. As the ground rose beyond the edge of the Prairie Dog town, I was more exposed to the full force of the wind, and to occasional spatters of light rain. It wasn’t fun, so I turned back, and decided to try the Jones Creek Trail. It turned out to be a little bit more sheltered, and I walked in for about half an hour, beneath the protecting buttes and amid the sagebrush.

Two female Northern Harriers flew above me, one apparently pursuing the other, twisting and turning through the tree tops, screaming at each other in the face of the high wind. I wanted to just keep walking for the rest of the day, but I had to drive halfway across Montana before nightfall, so I headed back.

When I was almost to the car I saw two people with binoculars around their necks. “Did you see the Harriers?” I said excitedly. They looked at me blankly. “Harriers?” said the man. “You’re not birders?” I said, pointing to the binoculars. “No,” said the man, with undisguised scorn. “Never mind,” I said, and didn’t bother to tell him what he had missed.

I stopped in Beach, North Dakota, for lunch; I avoided the fast food joint right next to the highway and drove a mile into the town and found La Playa Restaurant was open. In the restaurant, classical music was playing, and the young woman at the counter said, “Sit wherever you want, but not at a table that’s not clean yet.” A man with a graying pony tail sat across from a thin middle aged woman and talked about people they knew. An older woman with a grumpy face said to a young waitress, “There’s no lettuce left at the salad bar. The eggs are gone, too.” I ordered a small steak, medium rare. “Here’s your steak, darling,” said the waitress, and it came cooked perfectly. An elderly man and woman walked in, having a conversation that I’d describe as eccentric, with leaps of logic that I couldn’t follow. It was after two o’clock, and the music switched to a country rock radio station. The grumpy-faced woman ate methodically and stoically. I paid my bill, left the restaurant, and drove around a couple of blocks of downtown Beach. The town had a friendly feeling to it, and I particularly liked a hand-lettered sign in the park: PET POOPS YOU SCOOP.

The highway wound through the buttes and over the rivers and creeks of Montana. I was driving right into the teeth of that strong wind, so strong that the car was using about a fifth more gas than usual. I stopped for gas, and kept driving: a broad plain with cultivated fields; fantastically eroded buttes; a glimpse of a river with muddy water; softly rounded buttes; huge rolls of hay; cattle at a water hole; a small valley with a cluster of ranch buildings and trees whipping in the wind; another creek; another butte; the landscape passed by, always a little different, slowly changing as I drove onwards, the big sky overhead. I had a recording of of Terry Reilly’s minimalist masterpiece “In C,” and it seemed to fit the passing landscape perfectly: slowly changing, a sense of excitement and discovery slowly waxing and waning.

I stopped for a moment at a roadside rest area where I looked out over Rosebud Creek. The old Chinese art critics said the highest form of landscape painting depicted a landscape that you could wander in. This was a landscape you could wander in: the railroad winding between a cliff and a river; a large island in the river; ranch buildings just visible hear an there among the wide-spaced trees; mysterious bluffs in the distance leading to a hidden prairie beyond.

By the time I reached Billings, I had to buy gas. Carol had said Billings was worth stopping in. Had Carol been with me — Carol, that best of traveling companions, who always knows where the interesting places are to be found in any city — I’m sure I would have found the funky quarter where there are good cheap restaurants, a farmer’s market, a used bookstore, and a coffee shop with free wifi. But since Carol could not come on this trip, all I found was a supermarket and a gas station.

This post is for Carol, who asked for lots of photos.