This story of a Jain elder might wind up as one of a series of stories for liberal religious kids. Source and notes at the end.

Prabhava was one of the great teachers of the Jain religion. He wandered all over the earth teaching people to live a simple life, and to not be distracted by the pleasures of the senses, and to harm no living beings. Prbhava taught that if you could live like that, you could get rid of all your karma and achieve omniscience, so that you could see and know everything.

After Prabhava had been teaching for some time, he began to wonder who could take his place once he died. He thought about all his students and followers, but none of them (so he thought) would be able to take over for him. Then he used his upayoga power, that is, his mental sight, a power which allowed him to see everything in the whole world. He looked and looked until at last he saw someone who could take his place, a man named Sayyambhava.

This Sayyambhava was a priest of the Vedic religion, and when Prabhava saw him, Sayyambhava was in the city of Rajagriha, about to kill a goat as a sacrifice. Even though Sayyambhava was a priest in a religion that killed other living beings, because of his power of omniscience, Prabhava knew that he would make a good successor. “The beautiful lotus flower grows in the mud,” Prabhava said to himself, “so if you want a lotus flower you have to look in the mud.”

Prabhava went to Rajagriha to meet Sayyambhava. He sent two Jain monks ahead of him, and told them to go to the place where Sayyambhava was about to sacrifice the goat. “When you get there,” Prabhava told the two monks, “beg for food.” (Jain monks made their living by begging food from others.) “If the Vedic priests give you nothing, turn and walk away, and as you walk away, say in a loud voice, ‘Ah, it is too bad you do not know the Truth.'”

The monks got to the place where the sacrifice was about to take place, asked for alms, and when the Vedic priests refused to give them anything, they turned and walked away, saying in loud voices, “Ah, it is too bad you do not know the Truth.”

When Sayyambhava heard this strange remark, his mind became unsettled. Did these two monks know something that he didn’t know? Was his religion not the Truth? Instead of sacrificing the goat, he turned to his spiritual master, his guru, and asked, “Are the Vedas true — or not? Is our religion the path to the Truth — or not?”

His guru shrugged his shoulders.

Growing angry, Sayyambhava continued in a loud voice, “Those were holy monks, who obviously tell no lies. You’re not a true teacher, you’ve been lying to me all this time!” He took the dagger which he had been going to use to kill the goat. “Tell me the truth! If you don’t, I’ll cut off your head.”

Seeing that his life was in danger, the guru said, “I have not been telling you the truth. It is pointless to memorize the Vedas.” (The Vedas were the holy scriptures of the Vedic religion.) “Not only that,” the guru said, “but a statue of one of the Jain deities — a Jina, one of the highest Jain deities — is buried at the foot of the post where we tie to goats we are about to sacrifice.”

The guru pulled the sacrificial post out of the ground, and Sayyambhava looked down into the hole, where he saw a statue of a Jain deity. The guru went on, “There, that is a statue of the true religion. The only reason we do sacrifices is because we get to keep the meat afterwards. It’s an easy way to make a living. But what good is a religion that kills innocent animals? It is no good at all.

The guru pulled the sacrificial post out of the ground, and Sayyambhava looked down into the hole, where he saw a statue of a Jain deity. The guru went on, “There, that is a statue of the true religion. The only reason we do sacrifices is because we get to keep the meat afterwards. It’s an easy way to make a living. But what good is a religion that kills innocent animals? It is no good at all.

“Yes, I have been lying to you all these years,” said the guru to Sayyambhava. “Lying just so I could fill my stomach with easy food. But you are too good for that. Leave me, so that you can follow the true religion. If you do, I know that you will become all-seeing, and all-knowing.”

But Sayyambhava said, “You are still my teacher because in the end you told me the real truth.” Then Sayyambhava bid his guru a fond farewell, and went in search of the two Jain monks….

To be continued….

This story is from Canto 5:1-37 of The Lives of the Jain Elders, by Hemachandra (1098-1172). I used the following sources:

Sthaviravali Charita, or Parisishtaparvan, Being an Appendix of the Trishashtisalaka Purisha Charita by Hemachandra. Ed. by Herman Jacobi (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1891), pp. 39-41.

Hemacandra, The Lives of the Jain Elders, trans. R. C. C. Fynes (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 117-119.

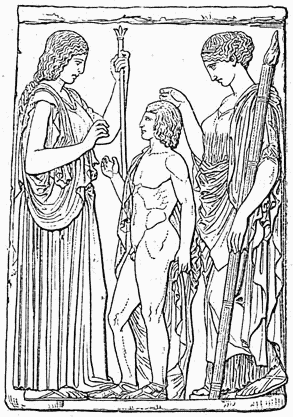

The image of the Jina is a modified Wikimedia Commons public domain image.