Read part one

Analysis:

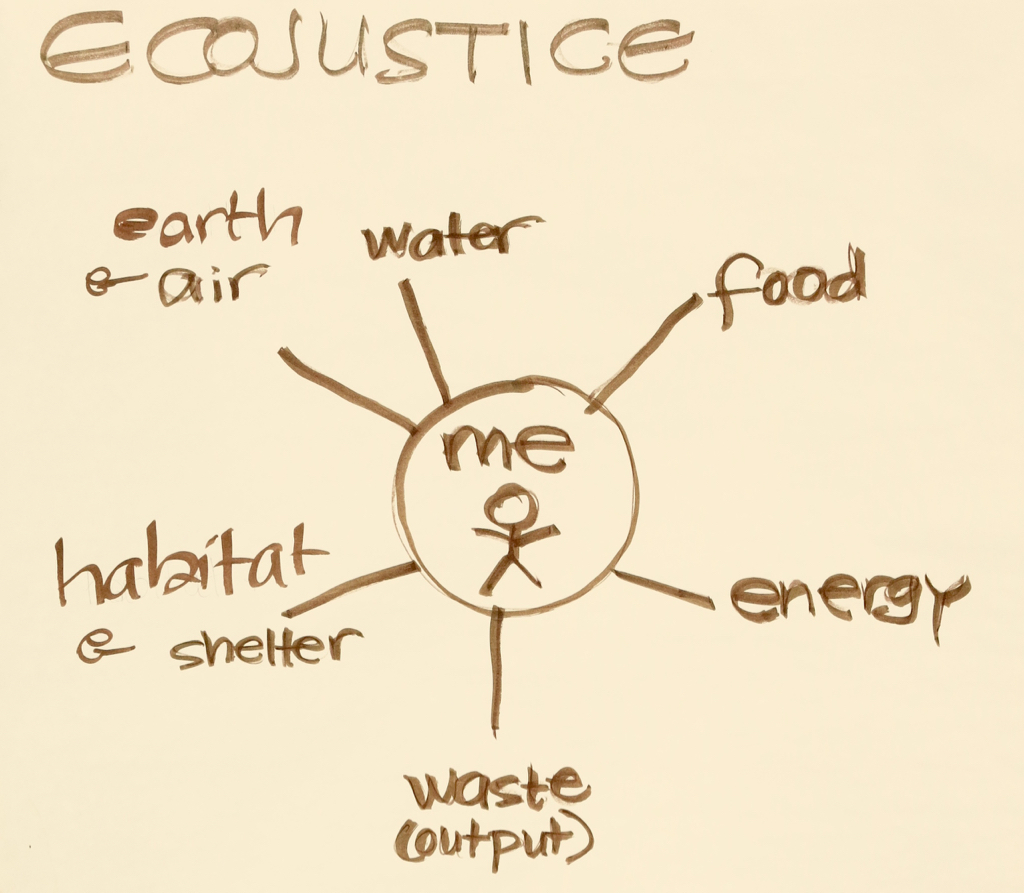

I’m always a little surprised at how much the children seem to like Ecojustice class; we do try to make Sunday school classes fun, but this class seems to be more fun than most. Late last year, I overheard a conversation that helps explain why. A seventh grader told a fifth grader, “You have to take the Ecojustice class. You actually get to do things.” When he said “You get to do things,” that seventh grader—who happens to be a non-praying atheist—did not mean his friend would get to pray or read sacred texts. He had grasped in an intuitive way that the curriculum of Ecojustice class is based on a progressive educational philosophy where “the learning experience is a part of life, not a separated preparation for life.” (23) While we aim to inculcate religious literacy and the core values of our religious tradition, including familiarity with sacred texts, these things cannot be taught separately from the lives we are in the midst of living.

Our progressive educational philosophy cause us to look with alarm at the seeming inability of local faith communities to address the global environmental crisis. We all know people of faith have to address the global environmental crisis, yet in spite of this apparent consensus “that religion must play a central role in building a more environmentally sustainable society, religious organizations and individuals have achieved few tangible results.” (24) Religions have done pretty well at linking their sacred texts and traditions to abstract thinking about environmental justice, but this does not seem to have had much effect in the real world. The specific conditions of the global environmental crisis require a new approach to ecological theology, just as the conditions of Latin America required the new approach of liberation theology; (25) sacred texts and theology cannot be treated separately from the immediate reality of our lives. To put this more directly: when I asked a group of elders at UUCPA about sacred texts and environmental ethics, one replied, “You don’t get your ethics by reading, … you get your ethics by living.” (26)

That seventh grader who urged his friend to do the Ecojustice class knew that words—whether spoken or written words—are not the most important teaching tool. In U.S. culture, we often equate teaching with explaining, which “makes teaching a talkative affair” where we assume that “to teach is to tell.” But this assumption is not accurate, because most teaching is actually nonverbal teaching. Example and experiences will always prove more powerful than speech: “No amount of talk can substitute for the well-placed gesture of the human body.” (27)

The teaching that takes place in the Ecojustice class is always connected with bodily movement and gesture. Before the class even begins, the children take part in the worship service, sitting near to other people of all different ages, standing up to sing, running out the door to their classes. When we arrive in the classroom, we sit in a circle so that we are aware of each other’s faces and bodies. When we say opening words together, we have hand motions to go with them. The children run to get food scraps and dead leaves to put into the composter; they pick up worms in their hands; they peer over a fence to look in the creek; they saw wood, hammer nails, and help hold things that other children are hammering and sawing; they pick up tools and materials and put them away. Of course I and the other teachers explain things with words, but those words are linked to specific bodily actions: hold the hammer like this, don’t forget to put a little water in the worm composter, etc. When we had the ethical discussion of removing House Sparrow eggs from the nesting box, this was not an abstract discussion, we were talking about a living organism that might cause a problem that we had to face with hands and hearts. At the end of class, when we say together “Hold fast to what is good” (based on words from a sacred text), we hold each other’s physical hands.

What these sixth graders, and us adult teachers, experience in the worship service and throughout the class can be understood metaphorically as a form of dance; not high-art dance done as a performance by professionals (e.g., ballet, modern dance, etc.), but participatory social dance done as a community. Even though our congregation rarely includes dance in our formal worship services (as is true of most religious groups stemming from the Christian tradition), you can find elements of informal social dance throughout the worship service, and in the liturgical elements interspersed through the class time: a time to stand and to sit, a time to greet each other in worship; a time to run pell-mell, a time to pick up worms; gestures and movements that express who we are and how we are interconnected. If we did not have these elements of dance, if we did not respect the bodies of all those in our congregation, it is likely that the children would be much less willing to be part of our congregation: “If children are screaming, they might just be having a bad day or else they might be doing what many of the adults feel like doing.” (28) Not that we always manage to respect the bodies of those in our congregation, but at our best, children, teens, and adults embody our values through dance-like moves.

Carla Walter, a dancer and scholar in our congregation, describes a womanist spirituality, drawing on African spirituality, which helps me understand what our post-Christian congregation aspires to. A womanist spirituality, says Walter, incorporating elements like dance, music, oral tradition, direct perception of spiritual matters, and relationships with other people, “draws on ancient knowledge of power in our spirits and communities to move us as it remembers the past, and on today’s hegemonically valued groups to work against intra- and intergroup hatred to build social sustainable structures. Spiritual wholeness is what is sought, in interconnectivity….” (29) This is what we are trying to do with our children and teens: make socially sustainable structures, seek spiritual wholeness. Womanist spirituality, a “struggle spirituality” that was never subject to Cartesian dualism and “the Adam and Eve mythos that informs Western religion,” (30) helps us dance through the resistance to Western religion; rather than correct interpretation of sacred texts to solve environmental problems, it nurtures spiritual wholeness and liberation through interconnectivity.

I don’t mean to suggest that scholars should give up re-interpreting sacred texts, like the Adam and Eve mythos in Genesis 2, to help solve environmental problems. And I appreciate the attempts to describe a straightforward connection from sacred texts to “ecological lived practices that continue to reshape an ecologically conscious social imaginary.” (31) But as a religious educator in a post-Christian congregation in the San Francisco Bay Area, I have found this approach is more likely to lead to restless children and resistant teens, and not a few restless and resistant adults.

Above: a dance choreographed by Carla Walter in a UUCPA worship service

Dance — “the earliest art form” which “allows expression that can’t approximate rational thought” (32) — lies closer to the embodied experience of young people than sacred texts. And while dance may not be prominent in sacred texts, it is there in the texts; in addition to re-interpreting Genesis 2, we might pay attention to texts like Exodus 15:20, where Miriam led women in celebratory dance, (33) as well as many other sacred texts that describe the relationship of human beings, other beings, and the divine in terms of processional dance, ecstatic dance, dances of praise and worship, etc. When we move out of the spheres of Western-style religion, and Westernized scholarship, we may find that dance is valued more highly. Professor Hyun Kyung Chung of Ewha Women’s University in Seoul gave an unusual presentation to the Seventh General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in 1991:

“Chung entered from the rear of the hall. She was accompanied by nineteen Korean dancers with bells, candles, drums, gongs, and clap sticks … [and] two Australian Aboriginal dancers dressed only in loincloths and body paint. … When they had all reached the stage, Chung and her companions stepped through a synchronized pattern [of dance] which combined Aboriginal movement with traditional Korean folk dance.” (34)

Some of those present experienced Chung’s presentation “electrifying, powerful, evocative,” while for others it was an “abject surrender of Christianity to a pagan environment.” (35) Many of us in the West have come to believe that hierarchies, orthodoxies, and standardized rituals define religion. Thus the General Assembly of the World Council of Churches gave a mixed response to Hyun Kyung Chung’s incorporation of dance into her presentation. Western Christianity (and Western religion more generally) has been preoccupied with hierarchies, creeds, and standardized rituals. But the majority of Christians now live in the global South, Christianity is no longer no longer shaped exclusively by Western-style religious practices, and Christianity is no longer defined by hierarchies, creeds, and standardized rituals. (36) This should cause us Westerners to rethink the definition of religion more broadly. We should remember that before Constantine’s deployment of Christianity in service of empire, Christianity “meant a dynamic lifestyle sustained by fellowships that were guided by both men and women and that reflected hope for the coming Reign of God.” (37)

In a post-Christian congregation such as the one I serve, children, teens, and their parents are rightly wary of religion that serves imperial ambitions; rightly suspicious of Western-style religion imposing its hierarchies and standardization on us. As we move away from standardization, then contemporary poems, like the one Beverly read at the beginning of the worship service I described, may serve as sacred texts. As we move away from standardization of religion, we may listen when an elder in our congregation vigorously asserts that “you don’t get your ethics by reading, you get your ethics by living,” we may notice the persons in our congregation who are preliterate children, and we may conclude that reading sacred texts isn’t as important as it has been in Western-style religion. Our bioregion and cultural context may also influences us: here in the San Francisco Bay watershed, an urban area on the Pacific Rim with a large East Asian population, we may find ourselves understanding religion in Asian terms, in non-Western terms, as “a matter of seasonal rituals, ethical insights, and narratives handed down from generation to generation.” (38)

The fact that we no longer have a centralized, standardized definition of what constitutes religion leads to uncertainty in how we conduct religious education here in the United States. Our closest religious cousins in the U.S., the liberal mainline Protestant Christians, also find themselves in the midst of this uncertainty. The disestablishment of Protestantism in the U.S., which occurred half a century ago, challenged mainline congregations—and post-Christian congregations like ours—to embrace “religious, racial, and cultural pluralism”; since then, we have been uncertain what religious education is supposed to accomplish, and who should do the educating. (39) And the uncertainty within religious education, the uncertainty with Western-style religion, is only magnified by the existential uncertainty of the global environmental crisis.

As we re-imagine religious education within our congregation, I find the image of the Web of Life helps to make sense out of the many and varied dance moves we engage in. Bernard Loomer, a theologian affiliated with both mainline Protestant and post-Christian congregations, described the Web of Life as “an indefinitely extended complex of interrelated, inter-dependent events or units of reality,” a complex which includes “the human and non-human, the organic and inorganic levels of life and existence”; what Jesus called the Kingdom of God was also the Web of Life, although this insight of Jesus’s was “covered over because we have surrounded Jesus with religiosity.” (40) In the Web of Life, humans and non-humans and the inorganic are all bound together in a web of relationships; reworking more traditional Christian terms, Loomer says that sin is when we act against this web of relationships, while forgiveness “is a restoration to those relationships.” (41) Loomer adds that as human civilization advances—as we achieve greater freedoms for minority groups, better understand the dignity of the other, etc.—we create the need “for adopting disciplines that are more complex and requiring virtues beyond anything the human spirit has known.” When Loomer said this in 1985, he remained uncertain whether we humans would be able to respond adequately to this challenge: “If the response is inadequate the human organism may turn out to be a dead end.” (42)

Facing this uncertainty, I am sometimes tempted to fall back on old educational models which impose certainty. I could make children and teens find spiritual certainty in a standardized body of sacred texts from which we extract truth. Or — something my congregation would feel more comfortable with — I could have children and teens find scientific certainty in technological fixes to the global environmental crisis. However, the best efforts of both science and Western religion have not decreased the probability of global environmental disaster, nor the probability that we humans will turn out to be a “dead end.” While I wouldn’t advocate abandoning either science or Western religion, they seem to me to be insufficient for making new “virtues beyond anything the human spirit has known.”

Imagine religion as a dance which restores us to the Web of Life, rather than acting against the relationships of the Web of Life. In this dance, we are interconnected with other persons as embodied beings bound in a web of relationships. Those relationships begin in the immediate human community where we are dancing; the relationships extend further into the immediate bioregion of the local watershed; and then still further into the relationships of the whole of the Web of Life. The relationships in the Web of Life are not neat and tidy; rather the Web of Life is a thicket and bramble wilderness filled with the messiness of becoming. In this dance, we communicate the reality of the Web of Life through gestures rather than through words or texts, through the interaction of the whole selves of embodied human beings.

As a religious educator, I hope to restore persons to their relationships of the Web of Life. To that end, the spiritual practices associated with womanist spirituality, including dance, music, narratives and oral tradition, direct perception of spiritual matters, relationships with other beings—spiritual practices that treat human beings as fully embodied beings—help connect children and teens (and adults too) to a spiritual wholeness within the Web of Life.

Our embodied approach to religious education might offer at least three helpful insights to more scholarly or theoretical approaches to mobilize religion to address the global environmental crisis. First, the children and teens in our post-Christian congregation are resistant to Western-style religion, associating it with intolerance and bigotry—associations that seem related to the imperial history of Western Christianity. Second, we see that the children and teens in our Pacific Rim congregation willingly and joyfully participate in dance-like embodied religious education—an educational approach that appears related to changes in global Christianity, and that can be conceptualized through womanist spirituality. Third, an accurate description of what I see in this post-Christian congregation does not lead to neat and tidy conclusions; instead I find myself in a thicket-and-bramble wilderness, where nothing about the messiness of becoming is clear and obvious.

A scholar of religion who walked into one of our classes and saw a bunch of sixth graders building birdhouses might be forgiven for thinking this class didn’t involve religion. Where are the texts, the beliefs, the prayers that define U.S. religiosity? Yet our post-Christian faith community might also be forgiven for thinking that organized religion has, so far, not been very effective in dealing with environmental crisis. It may not look like it on the surface, but our children and teens are dancing their way towards socially sustainable structures of spiritual wholeness. As the poet Marge Piercy says:

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot tell always by looking what is happening. (43)

Notes:

(23) This description of progressive educational philosophy is from Robert Pazmino, Foundational Issues in Christian Education 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2008), p. 120.

(24) Anna L. Peterson, “Talking the Walk: A Practice-based Environmental Ethic as Grounds for Hope,” in Ecospirit: Religions and Philosophies for the Earth, ed. Laurel Kearns and Catherine Kellar (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), 46.

(25) Ibid., 58.

(26) Cecil Bridges, personal communication, February 23, 2016. Cecil gave me permission to quote his words.

(27) Gabriel Moran, Fashioning Me a People Today: The Educational Insights of Maria Harris (New London, Conn..: Twenty-Third Publications, 2007), 51.

(28) Ibid., 81.

(29) Carla S. Walter, Dance, Consumerism, and Spirituality (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 49.

(30) Ibid., 48.

(31) Anne Marie Dalton and Henry C. Simmons, Ecotheology and the Practice of Hope (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2010), 105.

(32) Walter, 86.

(33) Ibid., 88.

(34) Harvey Cox, Fire from Heaven: The Rise of Pentecostal Spirituality and the Reshaping of Religion in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 1995/2001), 213.

(35) Ibid., 217.

(36) Harvey Cox, The Future of Faith (New York: HarperOne, 2009), 174.

(37) Ibid., 174, 179.

(38) Ibid., 221.

(39) Charles R. Foster, “Educating American Protestant Religious Educators,” Religious Education, 110 (2015), 548-550.

(40) Bernard C. Loomer, Unfoldings: Conversations from the Sunday Morning Seminars of Bernie Loomer (Berkeley, Calif.: First Unitarian Church, 1985), 1-2.

(41) Ibid., 3.

(42) Ibid., 19.

(43) Piercy, 128.