Ho Hsien-ku [Pinyin: He Xian’gu] is one of the Eight Taoist Immortals (Pa-hsien, Pinyin Baxian), and the only one who is unambiguously female. Six of the other Eight Immortals are definitely male, though at least one source (W. Perceval Yetts, “Eight Immortals,” p. 805) notes that Lan Ts’ai-ho may be depicted by artists as gender-ambiguous.

These Immortals began as humans, and transcended their humanity to become more than human. They could not be classed as either God or saint in the senses of those words used in the dominant Western religious traditions; but given their immortality and their powers, I would class them as deities. “The Eight Immortals are a group of seven men and one woman who are said to have attained immortality inspired by each other, and who continue to serve humanity by appearing in seances and inspirations” (Livia Kohn, Daoism and Chinese Culture, [Cambridge, Mass.: Three Pines Press, 2004], p. 164).

Below the photograph, I’ll append a brief biographical account of Ho Hsien-ku by W. Perceval Yetts, from “The Eight Immortals,” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (London: 1916), pp. 781-783 (endotes are Yetts’ own notes).

Above: Ho Hsien-ku with a lotus, an ivory sculpture made between 1850 and 1911 (Ch’ing Dynasty) at the Asian Art Museum (accession no. R2005.71.47).

“Ho Hsien-ku,” from “The Eight Immortals by Perceval Yetts:

Ho Hsien-ku is shown as a comely girl sometimes dressed in elaborate robes, but more often wearing over a simple garment the leafy cape and skirt affected by the hsien [English: enlightened one, immortal]. A large ladle is her recognized emblem. Its bowl, made of bamboo basketwork, is often filled with several objects associated with Taoist immortality, e.g., the magic fungus (1) and peach; (2) sprigs of bamboo and of pine; (3) and flowers of the narcissus. (4) The place of the ladle may be taken by the more picturesque long-stalked lotus bloom; and sometimes she holds just a fly-whisk or the basket of wild fruit and herbs gathered for her mother.

Biography from Lieh hsien chuan [Collected Biographies of Immortals by Lieh-hsien chuan], ii, 32, 33:

Ho Hsien-ku was the daughter of Ho T‘ai, of the town of Tsêng-ch‘êng, in the prefecture of Canton. At birth she had six long hairs on the crown of her head. When she was about 14 or 15 a divine personage appeared to her in a dream and instructed her to eat powdered mica, (5) in order that her body might become etherealized and immune from death. So she swallowed it, and also vowed to remain a virgin.

Up hill and down dale she used to flit just like a creature with wings. Every day at dawn she sallied forth, to return at dusk, bringing back mountain fruits she had gathered for her mother. Later on by slow degrees she gave up taking ordinary food. (6)

The Empress Wu (7) dispatched a messenger to summon her to attend at the palace, but on the way thither she [Ho Hsien-ku] disappeared. (8)

In the ching lung period (about A.D. 707) she ascended on high in broad daylight, (9) and became a hsien. In the ninth year of the t‘ien pao period (A.D. 750) Ho Hsien-ku reappeared, standing amidst rainbow clouds over a shrine dedicated to Ma Ku. Again, in the to li period (about A.D. 772) she appeared in the flesh on the Hsiao-shih Tower at Canton.

NOTES

[These are W. Perceval Yetts’s own notes.]

(1) This, the most ubiquitous object in Chinese art, has received various botanical names. (See Bretschneider, “Botanicum Sinicum,” Journal of the Chinese British Royal Asiatic Society, vol. xxv, p. 40, and vol. xxix, p. 418.) Its branches expand into flattened umbilicated extremities with scalloped edges. It is probably largely because of the resistance its wood-like substance offers to decay that it has been adopted as the emblem par excellence of immortality. There are records of its supernatural qualities having been recognized as early as the third century B.C. (see Chavannes, Les Mémoires historiques de Se-ma Ts’ien, vol. ii, p. 176 seq.), and to the present day it is sold by native apothecaries as a drug capable of prolonging life.

(2) Any representation of the magic peach is a covert allusion to that enigmatical figure, Hsi Wang Mu, the Queen of Taoist Fairyland. Among the wonders of her mountain domain was the tree that bore but once in 3,000 years peaches the taste of which gave immortality.

(3) Bamboo and pine, being evergreen, are emblems of longevity.

(4) The name the narcissus bears is sufficient reason why it should be included in this category.

(5) For the meaning of [what is here translated as “mica”]: see note by Dr. Laufer in T‘oung Pao, vol. xvi, p. 192. Perhaps a parallel may be found here between the alchemy of China and the West. Talc, a mineral often confused with mica, figures prominently in the writings of mediaeval alchemists, and as late as 1670 it was advocated as a mysterious preservative of youth and beauty by the Apothecary in Ordinary to the English Royal Honsehold, N. le Febure by name, in his Compleat Body of Chymistry, pt. ii, p. 106 seq.

(6) One of the first steps on the road to hsien-ship. Taoists are often said to have given up the ordinary diet of cereals. Some gradually reduce their food till they die of starvation. So emaciated is their condition that their bodies after death become mummified, and thus they do actually attain a kind of corporeal immortality. Particulars of this aspect of Chinese eschatology are to be found in an article by the writer in The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society for July, 1911.

(7) The notorious woman who, through the possession of an extraordinary personality and a genius for intrigue, rose from obscurity to become the supreme ruler of China during the latter part of the seventh century. See Mayers, Chinese Reader’s Manual, pt. i, No. 862; and Giles, Biographical Dictionary, No. 2331.

(8) I.e., Ho Hsien-ku eluded the envoy. Chinese legend abounds in instances of summonses to Court being sent to hermit sages and others who had cut themselves off from worldly affairs. The recipients have almost invariably shown a consistent contempt for mundane honors by refusing to comply, and imperial curiosity as to their reputed wisdom or powers of magic has remained unsatisfied.

(9) The actual period of the day or night when emancipation from earthly ties takes place and the final stage in becoming a hsien is completed is considered in Taoist lore to have a determining influence upon the subsequent career of the hsien. See, for example, the following passage from the Chi hsien lu: “When (after death) the body remains like that of a living man, the condition is that of release from the flesh, shih chieh; when the legs do not become discolored nor the skin wrinkled — that is shih chieh; when the eyes remain bright and unsunken, in no respect differing from those of a living man — that is shih chieh; when resuscitation follows death — that is shih chieh; when the corpse vanishes before it is encoffined, and when the hair falls off before the mortal body soars (to heaven) — both of these are shih chieh. Most perfect is the release that takes place in broad daylight, but less complete is the release that occurs at midnight. When it takes place at dawn or at dusk, then the persons concerned are relegated to a terrestrial abode” (i.e. they will not reach the celestial paradise, but remain in haunts of the hsien on earth, such as the K’un-lun Mountains, the Isles of the Blest, and the Five Sacred Hills).

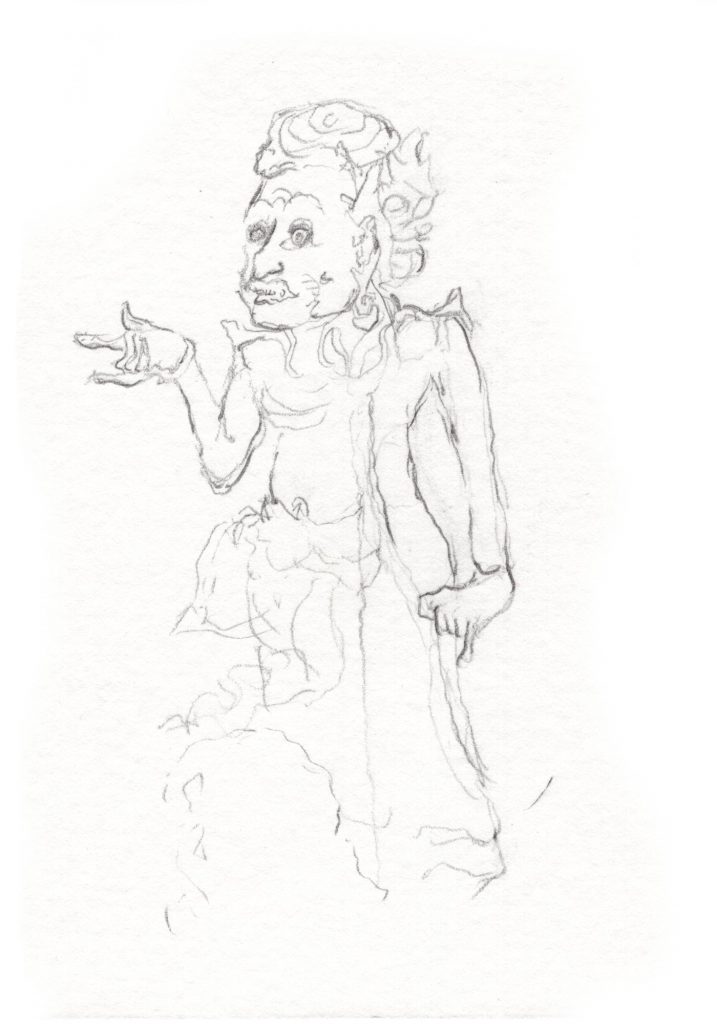

Above: Drawing of Ho Hsien-ku in Yetts, p. 781 (public domain image).