Standing in the creek bed of Purissima Creek, about two miles from Higgins Canyon Road.

Photo credit: Carol Steinfeld

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey

Standing in the creek bed of Purissima Creek, about two miles from Higgins Canyon Road.

Photo credit: Carol Steinfeld

Twenty years ago this month, I began working as a Director of Religious Education (DRE) in a Unitarian Universalist congregation. During the recession of the early 1990s, I had been working for a carpenter/cabinet-maker, so I had been supplementing my income with part-time work as a security guard at a lumber yard. Carol, my partner, saw an advertisement for a Director of Religious Education at a nearby Unitarian Universalist church. “You could do that,” she said. So I applied for the job, and since I was the only applicant, I got it.

Above: Carol took this Polaroid photo of me sitting at my desk at my first DRE job. The computer in the left foreground is a Mac SE, and I have a lot more hair. It was a long time ago.

Over the past twenty years, I worked as a religious educator for sixteen years — full-time for six of those years, part-time for nine years — and as a full-time parish minister for four years. Since I was parish minister in a small congregation where I had often had to help out the very part-time DRE, I feel as though I’ve worked at least part-time in religious education for twenty continuous years.

Sometimes I wonder why I’ve stuck with it so long. Religious education is a low-status line of work. Educators who work with children are accorded lower status in our society, because working with children is “women’s work,” and ours is still a sexist society. And religious educators are sometimes looked down upon by schoolteachers and other educators, because we’re not “real” educators. In addition to being low-status work, religious educators get low pay, and the decline of organized religion means our pay is declining, too, mostly because our hours are being cut, or paid positions are being completely eliminated.

After a week of twelve hour days, getting everything set for the first day of Sunday school, I was ready for a break. When Carol suggested we go for a late-afternoon walk at Purisima Creek Redwoods Open Space Preserve, I was ready to go.

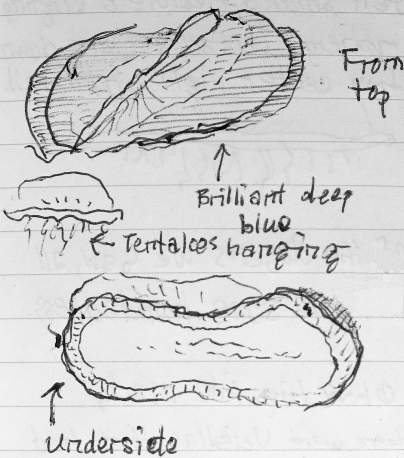

About an hour into our walk, Carol pointed down at the ground. “What’s that?” It was a small animal, dead. A mouse? No, a closer look revealed it was a mole. I turned it over carefully. There was a bit of a flat place where it had been lying; presumably decomposition was beginning. But you could still see the general shape of the animal. I admired it for a while then made a sketch, slightly smaller than the actual size of 110 mm total length, which I refined once we got home:

Of the two species of mole which inhabit our area, it was clearly a Shrew-mole (Neurotrichus gibbsii). According to Jameson and Peeters, in Mammals of California, we humans don’t really know what this species eats, or how it reproduces: “The Shrew-mole seems to feed indiscriminately on a board spectrum of soil-dwelling insects, pill-bugs, and centipedes”; it “appears to breed in late winter”; and “little is known of its reproductive habits” (my emphases). Another organism to which we humans live in close proximity, but about which we know little.

Usually, the myth of Persephone spending one third of the year in the underworld is supposed to explain why we have winter. But the climate in Greece is very like the climate in parts of California — winter is the rainy season, when the earth is green, and plants are growing. Martin Nilsson makes this point in his book Greek Popular Religion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1940), p. 51:

“For people who live in a northerly country, where the soil is frozen and covered by snow and ice during the winter and where the season during which everything sprouts and is green comprises about two thirds of the year, it is only natural to think that the Corn Maiden [Persephone] is absent during the four winter months and dwells in the upper world during the eight months of vegetation. And, in fact, this is what most people do think. But it is an ill-considered opinion, for it does not take into account the climatic conditions of Greece. In that country the corn [i.e., grain: barley or wheat] is sown in October. The crops sprout immediately, and they grow and thrive during our winter except for the two or three coldest weeks in January, when they come to a standstill for a short time. Snow is extremely rare and soon melts away. The crops ripen and are reaped in May and threshed in June. This description refers to Attica. The climate is of course different in the mountains, but Eleusis is situated in Attica. The cornfields are green and the crops grow and thrive during our winter, and yet we are asked to believe that the Corn Maiden is absent during this period. There is a period of about four months from the threshing in June to the autumn sowing in October during which the fields are barren and desolate; they are burned by the sun, and not a green stalk is seen on them. Yet we are asked to believe that during these four months the Corn Maiden is present. Obviously she is absent….”

And as I look out at the summer California landscape, where the hillsides are brown and dead-looking (especially this year, after three years of drought), I have to say it would make more sense that Persephone would be in the underworld right now, not in winter. In any case, although Nilsson’s book is a bit dated now, he reminds us that when the ancient Greeks thought of winter, they were not thinking of the stereotypical North American idea of winter, a time of snow and ice and cold.

But if this is not a myth about why it snows in winter, then what is it about?

Dr. Mara Lynn Keller, currently professor of women’s spirituality at the California Institute of Integral Studies, offers a feminist interpretation of the myth. Dr. Keller asserts that the myth of Demeter and Persephone focusses on “three interrelated dimensions of life: (1) fertility and birth; (2) sexuality and marriage; and (3) death and rebirth” (“The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, spring, 1988, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 31). Keller states that there is evidence to show this myth is an allegory of the role of women in developing agriculture:

“Some archaeologists and anthropologists conclude that plant domestication and thus the gift of agriculture came through women. This theory is corroborated by the mythic core of the Eleusinian Mysteries, where Demeter is said to give the gift of grain to the people and instruct them in the rites to be continued in her name.” (ibid., p. 31)

Further, Keller identifies Hecate as a grandmother figure, so the myth also is about cross-generational bonds: “The story of Persephone, Demeter and Hecate lets us see the loving bonds of daughter, mother, and grandmother. During the epoch of the Goddess religions, women were honored at all stages of life.” (ibid., p. 39) It is a story that started out as an allegory of the cycle of life. Later on, as patriarchal cultures moved in and conquered the older Goddess-worshiping matriarchal cultures, women were relegated to a secondary role. That would imply that this myth comes from that later patriarchal era, when a male god can force a female goddess into marriage — violating in the process those cross-generational bonds — without her consent or even prior knowledge.

This feminist interpretation of the myth has been hotly debated, and some scholars argue that the archaeological evidence does not fully support such an interpretation. Whether or not that is the case, this myth offers plenty of fodder for examining gender roles and the ways women may be dominated by men.

There are, of course, plenty of other interpretations. Dr. Eric Huntsman, professor of ancient scripture, classics and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Brigham Young University, summarizes some of the better-known interpretations of this myth in his lecture notes to Classical Civilization 241 (accessed 13 August 2014). Dr. Huntsman says this myth could be interpreted as:

— a myth related to the establishment of the Eleusinian Mysteries

— a nature myth about seed growth, and rebirth: Demeter allows no seeds to sprout on earth, when Persephone eats a seed she must return beneath the earth

— a myth about gender roles: females must struggle to define themselves in a world run by males

— a psychological myth about a young woman and her mother adjusting to the young woman’s marriage

— a psychological myth about a young woman growing up and figuring out her sexual identity

In short, this myth is not some pre-scientific attempt to explain why there are seasons!

I would like to suggest that there is at least some truth in several of these interpretations. Like a good poem, this myth contains multiple layers of truth and meaning, and these layers do not reveal themselves right away. Perhaps it is best that the layers of meaning reveal themselves slowly, over time. Emily Dickson could have been talking about the myth of Demeter and Persephone when she wrote:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

[poem #1263]

I’ve been researching a lesson plan for an upper elementary lesson on Oedipus and the Sphinx. This research led me to a mathematical game or puzzle involving sphinxes.

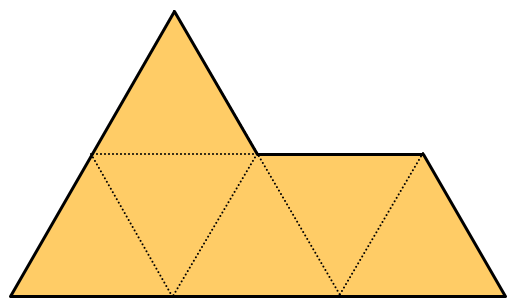

The “sphinx” of this puzzle is a five-sided figure, made up of six equilateral triangles:

This pentagon is called a sphinx because it looks a little like the giant Egyptian Sphinx at Giza — see below. In the image below, you can see that unlike the Greek Sphinx, the Egyptian Sphinx did not have wings. However, in spite of this difference, the Greeks traced the origins of their Sphinx back to Egyptian Sphinxes.

The interesting thing about the sphinx shape is that you can make larger sphinxes using smaller sphinxes (alternatively, you can dissect a larger sphinx into smaller copies of itself, though from a practical puzzle standpoint that’s difficult). Here’s how to try this out yourself. Below is a printable sheet of sphinx shapes that you can print onto heavy paper to be cut out:

Click here for a PDF of sphinx shapes for cutting out

OK, print out at least two sheets of the above PDF. Now here are several sphinx puzzles for you:

(1) Cut out 4 sphinx shapes to start, and make 1 larger sphinx shape from those 4. When you complete this puzzle, you have made a Size 2 Sphinx.

(2) Cut out a total of 16 sphinx shapes, and now make Size 4 Sphinx. (If you think about it for a moment, you should see an easy way to do this.)

(3) Making a Size 4 Sphinx was pretty easy, right? Now make a Size 3 Sphinx.

OK, those are the basic Sphinx puzzles. You’ve seen how smaller sphinxes can be made into larger sphinxes (or, conversely, how a larger sphinx may be dissected into smaller copies of itself). But this is just the beginning. If you want to keep going, here are some more challenges:

(4) We already said that making a Size 4 Sphinx is easy. But supposedly there are a total of 16 ways to make a Size 4 Sphinx. Can you find all 16 ways? (I have not yet done this.) Hmm, is there a proof to show that there are only 16 ways? (I have no idea!)

(5) Oh, and by the way, there are 4 different ways to make a Size 3 Sphinx. Can you find all 4? (I found this relatively easy.) Hmm, what about a proof showing there are only 4 ways? (Again, no idea!)

(6) It takes 4 sphinx shapes to make a Size 2 Sphinx; it takes 9 sphinx shapes to make a Size 3 Sphinx; it takes 16 sphinx shapes to make a Size 4 Sphinx. Do you care to predict how many sphinx shapes it takes to make a Size 5 Sphinx? (Easy.) Now try to make a Size 5 Sphinx. (Warning: not easy!)

(7) While you are at it, how about making a Size 6 Sphinx? And then can you make a Size 7 Sphinx?

(8) It’s easy to make a Size 8 Sphinx. That’s a lot of pieces to cut out, though — you can cheat by drawing 4 smaller sphinx shapes onto each sphinx shape. Will this technique help you make a Size 5 Sphinx? (Not really, but…) If not, what about making other shapes that can be subdivided into sphinx shapes — will that help? (For what it’s worth, one mathematician used this approach to try to prove how many different solutions there are to the Size 5 Sphinx.)

(9) There is 1 way of making a Size 2 Sphinx. There are 4 ways to make a Size 3 Sphinx; there are 16 ways of making a Size 4 Sphinx. Can you figure out how many ways there are to make a Size 5 Sphinx? (Warning: this is a problem that has challenged professional mathematicians, and to the best of my knowledge no one has proved how many solutions there are to a Size 5 Sphinx.)

There are still more puzzles and challenges to be found in the sphinx. You can find lots of them at the Mathematics Centre of Australia — click here.

The sphinx is one example of a rep-tile (self-replicating tiling), a polygon that can be dissected into smaller copies of itself. In shape, a sphinx is a pentagonal hexiamond (i.e., it has 5 sides, and it is made up by sticking 6 triangles together); further, it is an asymmetric rep-tile, since it comes in both left-handed and right-handed varieties and you need both varieties to dissect a sphinx. Note that a sphinx can be dissected into 4, or 9, or 25, or … copies of itself. According to the too-brief and not-entirely-accurate article at Wikipedia, the sphinx is the only (known?) pentagonal rep-tile.

Beyond this, I am getting in over my head. I think if the Sphinx had asked Oedipus to solve all 150+ Size 5 Sphinxes, he would have failed, she would have gobbled him up, and she would still be sitting outside Thebes terrorizing the city. Having said that, I would love to hear from you if you are a mathematician who can correct any errors I may made.

This afternoon, we went for a walk at Purissima Creek Redwoods Open Space Preserve in the Santa Cruz Mountains southwest of San Mateo. It was a stunning afternoon, warm but not too hot, with fog beginning to roll in up the canyons from the ocean.

As we hiked down into the preserve, we kept hearing a hawk screaming somewhere in the distance, but we never saw it. And then when we were hiking back up to the parking lot, there it was overhead: an accipter flying over the ridge we were on, then turning and riding the breeze coming up the canyon to our right. And what kind of accipter was it, a Cooper’s Hawk or a Sharp-shinned Hawk? I’d say it was perhaps a little larger, the neck a little longer, the tail a little more rounded, the wingbeats a little more deliberate: probably a Cooper’s Hawk, but I’m not good enough at field identification to be sure. It wheeled around, high above the canyon floor but at eye level for us; a couple of Band-tailed Pigeons came over the ridge, saw the accipter, and quickly ducked into the trees below us. Then the fog rolled up the canyon, and it was gone.

As we continued up the trail, Carol got about a hundred feet in front of me. Suddenly we both froze: walking the trail well up the hill in front of us was a dog-sized canid: a Gray Fox, its long tail behind it, its head turning from side to side, giving us a flash of the rufous fur up the side of the neck. It didn’t seem to notice us; it was busy watching the undergrowth on either side of the trail, and at least once it pounced at something.

We got back to the car a little after seven, and decided to go down to the beach to eat dinner. It was a beautiful foggy evening, and we walked along past Heerman’s and California Gulls, but the real attraction of the beach was the Velella velellas. When I was reading up on this species last night, I found a Web page by Dr. David Cowles that gave a possible reason why so many Velella velellas have washed up on northern California beaches:

“The angled sail makes it sail at 45 degrees from the prevailing wind. Some have a sail angled to the left, others to the right. Off California the right-angled form prevails, and these remain offshore in the prevailing northerly winds. Strong southerly or westerly winds, however, may bring huge aggregations ashore.”

We walked down the beach, making an unscientific survey: of the dozens of individuals we saw — ranging in size from less than two inches long to one that was as long as my notebook or approximately four inches (10 cm) long — all the sails had the same handedness (according to Dr. Cowles’ terminology, right-angled sails). Here’s a sketch from my notebook:

I picked one up by its sail to look at the tentacles hanging down underneath. The velellas, like the fox and accipter, are predators, feeding on smaller organisms with their dangling tentacles. The tentacles seemed to descend from the central oval, and were of varying lengths. The sail itself felt smooth, flexible, and slightly rubbery; I dropped it back into the waves after I had looked at it.

Three very different predators — but each one a fabulously beautiful organism.

My cousin and her husband were visiting from Seattle, and she wanted to go to the beach to see the sun set in the Pacific. So Carol and I and the two of them drove over the Coastal Range to Half Moon Bay.

“Maybe we’ll see the velellas,” said Carol. The velellas — scientific name Velella velella — are small bright blue creatures that are distant relations of the jellyfishes. They float on the surface of the ocean, feeding underneath the water with tiny tentacles, and being blown about by the wind on their small sail. Recently, hundreds of them have been blown up along the shore in San Francisco and Santa Cruz and Humboldt County. But I was skeptical that we’d see velellas, since I had seen nothing about them being blown onto beaches in San Mateo County.

When we got to the beach, the fog was so thick it was obvious that we weren’t going to see the sun set in the Pacific. But Carol said, with a big grin, “Look, the velellas!” Sure enough, all over the beach just above the line of waves, were these little blue things. The biggest one I saw would fit easily in my hand.

When you got down and looked at them closely, they were beautiful and amazing creatures. The San Francisco Chronicle interviewed Jim Watanabe, who works at the Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey County; the newspaper quotes him as saying, “They’re a nice reminder of the diversity of other life in the sea that we sometimes don’t think about.”

The velella turns out to be a highly interesting organism that is not particularly well understood, as this Web page from Walla Walla University points out.

Nights get cool in the dry desert air of Elko, and we left the window of the motel room open all night. We got on the road while the air was still cool. We were about to turn on the audiobook we have been listening to — Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in the translation by Burton Raffles — when I saw a sign by the side of the road: “California Trail Interpretive Center.”

“Do you mind if we stop there?” I said to Carol. She knew that I have become mildly obsessed with the California Trail on this trip, so she agreed we could stop.

We climbed up the short trail behind the Interpretive Center building, and looked down on the Humboldt River valley: the narrow river winding along the low point of the broad valley; bright green grass and even a few trees growing near the river; the green grass giving way to sagebrush as the land sloped up away from the river; and then, rising more and more steeply above the level of the sagebrush, the stark and almost bare slopes of towering mountains.

Above: The Humboldt River valley east of Elko, Nev.

Edwin Bryant, in his 1848 book What I Saw in California, described how his party made the difficult crossing of the salt flats west of Great Salt Lake, and then made their way across the often steep and difficult terrain of what is now western Nevada, finding barely enough water, and barely enough grass for their mules, at widely spaced springs. After more than a week of travel through this harsh desert, Bryant and his party found a small tributary stream which finally led them to the Humboldt River (which they called Mary’s River):

“We emerged into the spacious valley of Mary’s River, the sight of which gladdened our eyes about three o’clock, P.M. At this point the valley is some twenty or thirty miles in breadth, and the lines of willows indicating the existence of streams of running water are so numerous and diverse, that we found it difficult to determine which was the main river and its exact course…. At sunset we encamped in the valley of the stream down which we had descended, in a bottom covered with the most luxuriant and nutritious grass. Our mules fared most sumptuously both for food and water.”

Today, the Humboldt River valley looks somewhat different than it did in Bryant’s day: the river has been restricted to one main channel; most of the trees are gone and the river bottoms are used by farmers to grow feed for cattle; cattle graze on sagebrush above the river bottom; and the interstate highway and a railroad run between the agricultural land and the grazing land. But even in this time of interstate highways and air conditioned automobiles, I still found the green of the valley to be a welcome sight in the midst of a land that appeared to me to be dry and forbidding landscape.

My perception of this land as dry and forbidding is not shared by the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshones. On their tribal Web site, they write: “This vast land of mountains, valleys, deserts, rivers, and lakes offered an abundance of wildlife and plants for the Shoshone to hunt, fish, and gather. The Newe [the name by which they call themselves] knew their lands and cared for its natural balance; for them it was a land of plenty.” And, Steven J. Crum, in his book The Road on Which We Came: A History of the Western Shoshone (Salt Lake City University of Utah Press, 1994), quotes a Western Shoshone song:

“How beautiful is our land,

how beautiful is our land,

forever, beside the water, the water,

how beautiful is our land.

“How beautiful is our land,

how beautiful is our land,

Earth, with flowers on it, next to the water,

how beautiful is our land.”

We kept driving west, generally following the course of the Humboldt River, for the next two or three horus. Bryant and his party followed the Humboldt River for more than a week, from August 9 through August 19, when at last they reached the Humboldt Sink — that place where the river terminates:

“We came to some pools of standing water, as described by the Indians last night, covered with a yellowish slime, and emitting a most disagreeable odor. The margins of these pools are whitened with an alkaline deposit, and green tufts of a coarse grass, and some reeds or flags, raise themselves above the snow-like soil.”

The Humboldt Sink is another weird landscape, forty-five miles of undrinkable water, halophytes or salt-loving plants, whitish soil — and forty-five miles of misery for the early travelers along the California Trail. The Western Shoshone appear to have been smart enough to stay out of the Humboldt Sink. But the white emigrants had to cross it in order to get to California. Mark Twain had to cross it in his 1861 trip by stagecoach in order to get to his final destination of Carson City:

“…forty memorable miles of bottomless sand, into which the coach wheels sunk from six inches to a foot…. It was a dreary pull and a long and thirsty one, for we had no water. From one extremity of this desert to the other, the road was white with the bones of oxen and horses. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that we could have walked the forty miles and set our feet on a bone at every step! The desert was one prodigious graveyard. And the log-chains, wagon tyres, and rotting wrecks of vehicles were almost as thick as the bones. I think we saw log-chains enough rusting there in the desert, to reach across any State in the Union. Do not these relics suggest something of an idea of the fearful suffering and privation the early emigrants to California endured?”

Above: The Humboldt Sink near Interstate 80 in Nevada

Why did those early emigrants make that trip? — traveling west for hundreds of miles into uncertainty. The emigrants may have been able to give rational explanations of their desire to emigrate; but, suggests historian George R. Stewart, there were other, non-rational, factors at work:

“We may suspect some unconscious motivation. Moving was an established folk custom. Most of these people had already moved once, or oftener, and to do so again was only natural. Moreover we may suspect that many of them were driven on by mere boredom. To exist for a few years on a backwoods farm with almost no means of amusement or stimulation meant the build-up of an overwhelming desire to see new places and people.” (The California Trail [New York: McGraw Hill, 1962].)

It seems a little extreme to suggest someone would travel that far into such uncertainty out of boredom; Mark Twain was driven to emigrate to Nevada out of a species of boredom, but that was later, when there was regular stagecoach service across the continent. But boredom is related to other human feelings, including religious feelings — what is meditation, but organized boredom? — and as meditation is related to boredom, so are both related to ecstasy. The early travelers along the California Trail must have endured mind-numbing boredom at some stages along the trail; but in other places they experienced the terrifying sublimity, the awe-inspiring grandeur, of the land; the awe and sublimity and terror amplified by partial starvation and fear and exhaustion, and their earlier boredom. We drove most of the day through the Nevada landscape on not enough sleep, we were sometimes bored by driving, and we were awe-struck by the sight of the mountains and canyons; terrified by the steep winding downgrades; horrified by the sight of a fire-blackened hulk of a truck that we passed in slow single-file line of vehicles as fire fighters put out the last of the brush fire that the explosive burning of the truck had started, passed in horrified realization that no one could possibly be left alive after that crash and fire, that crash that obviously came from the truck losing control on one of those steep winding downgrades that we were now negotiating. The emigrants had far more intense experiences that lasted far longer, and extended over months. Such things work changes on one’s being.

On the other side of the Humboldt Sink, the interstate roughly follows the Truckee River — again, one of the routes of the California Trail, a route that guaranteed fresh water and forage for oxen and mules. We stopped at the rest area at Donner Pass — this rest area is not far from where the ill-fated Donner party were snowbound, and where nearly half the party died — and to stretch our legs we walked a short distance along the Pacific Crest Trail.

There we met a man who was through-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. He was older than the typical through-hiker, ten or twelve years older than I, and since we were near contemporaries of his, it was easy to wind up talking with him. He told us about walking 700 miles through the desert, sometimes having to carry enough water to last him for 30 miles. When he got to the high Sierras, the altitude hit him hard, slowing him down until he became finally acclimated. Carol asked about the logistics of renewing his supplies, and he said that once he had to walk a full day, or about fifteen miles, off the trail to pick up supplies, and then walk a full day to get back on the trail.

His motivation for taking on such a physically and mentally challenging trip was simple: his son was killed in an accident, then his wife died, and he had to do something. We talked about what might motivate other through-hikers. “We’re listening to The Canterbury Tales as we drive,” I said, “and I think through-hiking is a kind of modern-day pilgrimage.” Through-hikers have no pilgrimage destination, no Canterbury with Saint Thomas’s remains at journey’s end; there is only the journey. But like the pilgrims going to Canterbury, and like the emigrants, they begin their journeys with the advent of warm weather:

“When Zephyrus eke with his swoote breath

Inspired hath in every holt and heath

The tender croppes and the younge sun

Hath in the Ram his halfe course y-run,

And smalle fowles make melody,

That sleepen all the night with open eye,

(So pricketh them nature in their corages);

Then longe folk to go on pilgrimages….”

So, too, I began to long for this cross-country trip in the early spring, looking through the road atlas to choose a route, making plans about where we would stop, dreaming about when we could start driving.

All pilgrims must complete their journeys before the harsh weather of winter sets in. Our through-hiker worried that he might be walking too slowly, he might not make it through the mountains of Washington before the winter snows set in. I said I wasn’t sure that mattered, and he allowed that the journey was what he most wanted, and needed.

As for us, our journey is almost complete. Our journey has been relatively comfortable: riding in a car, stopping when we feel like it to take a walk or look at scenery, sleeping in motels. Our journey has been relatively quick: a matter of days, not weeks or months. But as we drove down out of the Sierra Nevadas, down into the wide Central Valley, through the traffic of Sacramento, I feel a change in myself — not enough of a change, but a change. That’s what the early emigrants on the California Trail were looking for: a change; a change in circumstances, but also I think an inner change. Mark Twain was looking for a change in circumstances when he went by overland stage to Carson City, Nevada, and after seven years in the West found that what had changed most was — not external circumstances — but himself.

We kept on driving west, driving towards the sun setting over the Coastal Range, the western-most range of mountains in this part of North America.

Above: The Coastal Range near Winters, Calif.

Somewhere beyond those purple mountains lies San Francisco Bay, on the edge of which we live; and beyond one last ridge of the Coastal Range lies the Pacific Ocean, extending into vastness beyond the limits of sight. And as we see the sun set behind the mountains, we know that we will not reach our final destination before night settles in on us.

We made a detour to Red Canyon, part of Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area. For an hour and a half, we walked through Ponderosa pine woods, stopping now and again at one of the overlooks set up to offer perfect picture postcard views of the sheer red sandstone walls of the canyon dropping a thousand feet down to the perfect emerald water of the reservoir. It is almost impossible to take a bad photograph of Red Canyon.

Above: Red Canyon, Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area in Utah

We drove back to the interstate, across broad sagebrush-covered plains, down steep, twisting roads, emerging every once in a while into valleys that were bright green with irrigated agricultural fields.

Sagebrush and mountains dominated the landscape. The interstate plunged down into Echo Canyon, historic route of the Hastings Cutoff on the California Trail. Somewhere in Echo Canyon there are the remains of stone breastworks erected by early Mormons as an act of defiance, as they prepared for an invasion by the U.S. Army; the army had spent months moving its troops westward and was camped out for the winter near Fort Bridger, Wyoming, prepared to forcibly extend the territorial rule of the United States over the Mormon theocracy. Open war was averted, barely. Eventually the coming of the railroad changed the political landscape, by making it far more difficult for the Mormon hierarchy to remain so isolated — and by making it obvious to all concerned that the U.S. Army could mobilize forces, not in a matter of months, but in a matter of days.

We stopped at a rest area in Echo Canyon, and climbed a fifty-foot high hill that was covered in sagebrush bushes ranging in height from two feet to the extraordinary height of seven feet. I looked at one of the seven-foot-high sagebrush bushes. Mark Twain was right; squinting my eyes and using my imagination, the sagebrush turned from a small bush into a huge old tree towering over me:

“If the reader can imagine a gnarled and venerable live oak-tree reduced to a little shrub two feet-high, with its rough bark, its foliage, its twisted boughs, all complete, he can picture the ‘sage-brush’ exactly. Often, on lazy afternoons in the mountains, I have lain on the ground with my face under a sage-bush, and entertained myself with fancying that the gnats among its foliage were liliputian birds, and that the ants marching and countermarching about its base were liliputian flocks and herds, and myself some vast loafer from Brobdignag waiting to catch a little citizen and eat him.”

Above: Seven-foot high sagebrush in Echo Canyon, Utah

As we drove along, I compared our route on a map of the California Trail published by the National Park Service; I also looked at the official highway map of the state of Utah, which shows the historic route of the Hastings Cutoff of the California Trail, in greater detail and with more accuracy than the Park Service map. After Echo Canyon, the Hastings Cutoff went north of present-day Interstate 80. Leaving Salt Lake City, the interstate crosses a part of Great Salt Lake that is often dry, while the Hastings Cutoff followed higher ground along the base of Oquirrh Mountain, then in along the Tooele Valley, and up over Hastings Pass. The old trail passed by some fresh water springs, crossed over the present route of Interstate 80, then across great slat flats.

It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like to cross the utterly flat and utterly white salt flats in the days of the California Trail — neither fresh water nor forage for the oxen or humans, blinding sun above reflected by pure white salt underfoot — it seems impossible; yet people did it.

We drove at 75 miles per hour along a perfectly straight and level highway, watching the sun slowly sink towards the mountains on the Nevada side of the salt flats. We got to the rest area on the western edge of the slat flats just before sunset, and took innumerable photos of the subtly changing light in the sky, on the distant mountains, on the salt flats themselves. The beauty of the scene was tamed by the knowledge that we could get back into our automobile, and within minutes be sitting in an air conditioned restaurant in Wendover, drinking fresh water; without that sense of physical safety, the beauty would better be described as sublime and awe-inspiring.

We watched the shifting color, but we also watched the dozens of people who pulled their car or truck or RV into the rest area, and leaped out, camera or smartphone in hand, to take as many photos as we were taking. A family group came out of two rental RVs speaking Polish, children running across the slat flats, adults staring and taking photo after photo. A trucker walked swiftly to the edge of the slat flats, holding up his smartphone to take photos. And off to one side, half a dozen people took part in some kind of photo shoot: a woman in a long red dress, a girl holding a bright pink helium balloon, a photographer with a backpack and cameras slung around the neck.

Kearney, Neb., is named after Fort Kearny, an army outpost established in 1848 to help protect the emigrants who were using the Oregon Trail in increasing numbers in the middle nineteenth century. As Interstate 80 heads west of Kearney, it roughly follows the old Oregon Trail along the Platte River, crossing and recrossing the Platte on anonymous bridges that you wouldn’t notice except for small signs identifying which channel or branch of the Platte you are driving over at 75 miles per hour. But in his 1847 book The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life, Francis Parkman tells of a very different experience crossing the Platte River:

“The emigrants re-crossed the river, and we prepared to follow. First the heavy ox-wagons plunged down the bank, and dragged slowly over the sand-beds; sometimes the hoofs of the oxen were scarcely wetted by the thin sheet of water; and the next moment the river would be boiling against their sides, and eddying fiercely around the wheels. Inch by inch they receded from the shore, dwindling every moment, until at length they seemed to be floating far in the very middle of the river. A more critical experiment awaited us; for our little mule-cart was but ill-fitted for the passage of so swift a stream. We watched it with anxiety till it seemed to be a little motionless white speck in the midst of the waters; and it WAS motionless, for it had stuck fast in a quicksand. The little mules were losing their footing, the wheels were sinking deeper and deeper, and the water began to rise through the bottom and drench the goods within. All of us who had remained on the hither bank galloped to the rescue; the men jumped into the water, adding their strength to that of the mules, until by much effort the cart was extricated, and conveyed in safety across.”

We stopped at Gothenberg, Neb., to see the Pony Express station. The pleasant woman sitting in the station told us it was relocated from a ranch about thirty miles away, reassembled in the town park, a new roof put on, a brick floor put down, and concrete put between the logs to keep the weather out.

On the way out of town, we stopped at Lisa’s Kitchen for an early lunch. Lisa was outside watering the flowers in front of the restaurant, and she came in to take our order. While she cooked my hamburger, she and I got to talking. I admired the photographs of her grandchildren. There was also a framed photograph of her daughter hanging on one wall, and on the opposite wall a large framed photograph of Lisa, looking quite glamorous and scholarly, from when she lived in Hong Kong. When she heard that Carol and I live in the Bay Area, she said that her daughter lives in the Mission District in San Francisco. She and I agreed that the price of housing in the Bay Area is ridiculously high.

As we were getting in to the car, she waved at us, picked a lily, and came over and gave it to us. The blossom stayed in a large paper cup in the center console of the car for the rest of the day.

We stopped to have lunch at a rest area in Nebraska. We got out of the car, and it seemed warm and windy, but not oppressively hot — just comfortably warm. When I checked the thermometer, however, it read 99 degrees! We were back in the West, where the dry heat isn’t uncomfortable, it just sucks all the moisture out of your body until you feel faint. Carol had washed a pair of pajamas and we hung them out to dry while we were eating lunch, but they were probably dry before we had even opened the jam jar to make our sandwiches.

Before long, trees started to disappear from the landscape, and we began to see sagebrush growing alongside the highway. This was another sign that we were entering the West. The interstate climbed up the western end of Nebraska, we topped one rise and there, off in the blue distance, were the sharp peaks of the distant mountains. We crossed over the border into Wyoming, and soon saw snow-covered peaks. Mark Twain, in Roughing It, described his delight the first time he saw snow-covered peaks in the West:

“Two miles beyond South Pass City we saw for the first time that mysterious marvel which all Western untraveled boys have heard of and fully believe in, but are sure to be astounded at when they see it with their own eyes, nevertheless–banks of snow in dead summer time. We were now far up toward the sky, and knew all the time that we must presently encounter lofty summits clad in the ‘eternal snow’ which was so common place a matter of mention in books, and yet when I did see it glittering in the sun on stately domes in the distance and knew the month was August and that my coat was hanging up because it was too warm to wear it, I was full as much amazed as if I never had heard of snow in August before.”

He had spent several weary weeks in an overland stage before he saw that delightful sight; we had driven just a few days.

We stopped for dinner at a rest area in the Wagonhound region of Wyoming. A sign proclaimed that Indians had used the same spot for a rest area:

“The stone circles or ‘TIPI RINGS’ at this site mark the location of a prehistoric Native American campsite. The stones were probably used to anchor the skins of conical tents, known by the Sioux word ‘TIPI’…. It has been estimated that there are over 1 million tipi rings in the western United States. As such, they are one of the most common archaeological features to be found in this part of the country.”

Certainly, those prehistoric Native people picked a beautiful spot to set up their tipi.

Above: The Wagonhound region of Wyoming

Sagebrush, snow-covered mountains, Indians — one more thing was needed for us to know that we were truly in the West: evidence of major resource extraction. But soon we saw a huge refinery alongside the interstate, out in the middle of nowhere:

Above: Refinery near Sinclair, Wyo.

Then we passed an open pit mine that stretched for over two miles: huge piles of dirt with huge earthmoving equipment crawling over them; the top of a crane emerging from a some deep hole not far from the highway. Now we were truly in the West.