I’ve been researching the race riot that happened at the high school in my hometown in 1978 (I hope to have a blog post about it on the 45th anniversary of the actual event). Part of my research led me to a 2002 oral history interview with Phil Benicasa, for many years an elementary school principal in Concord. I never knew him, but my younger sister worked as a reading tutor in his school for a few years, and always had good things to say about him as an educator.

So here’s what Phil Benicasa said about parents and education back in 2002, not long before he retired:

“[S]omething is going on with the youngster who comes to our door in kindergarten [in 2002] as opposed to the youngster that came to our door 20 or 25 years ago. They are nowhere near as well prepared for the conventions of learning as kids were some time ago. I think parents are confused about parenting. I think kids therefore are confused about their role as children. In 1975 if you took the chunk of time out of my week that I spent doing discipline, 80% or 90% of that would have been at the fourth and fifth grade level, and more often than not it was mischievous sort of stuff. It was the kind of stuff that you could chew out a kid for and send him out of the office and chuckle about what it was that the kid had done. Today 80 to 90% of my time in discipline is spent in kindergarten, first, and second grade. That’s astonishing. And it’s not mischief. There are really a tragic number of kids with social and emotional baggage that they are having great difficulty casting off….

“I think parents have bought into the business about, the sooner my kid learns to read, the better they’re going to be. If my kid learns to read by age 3, that’s a direct line to Harvard. That’s absolutely nonsense. There are so many more important things that need to be learned before they get to us [in elementary school]. You know that business, ‘everything I needed to know, I learned in kindergarten’? — to clean up after myself, to share, to listen to others, to wait my turn, not cut ahead — all that’s true. Generally speaking kids had much of that in place before they arrived in the door.… [K]ids are not coming to school in kindergarten as well prepared to take advantage of what it is we are offering than they have been in the past. That means we have to modify what we are offering.”

Three obvious caveats — (1) This statement represents the observations and opinion of just one educator. (2) Phil Benicasa’s observations were limited to Concord, a predominantly White town in New England. (3) The demographics of Concord’s schools changed from 1975 to 2002, from an economically diverse cohort of children, to a nearly homogenous upper-upper middle class cohort.

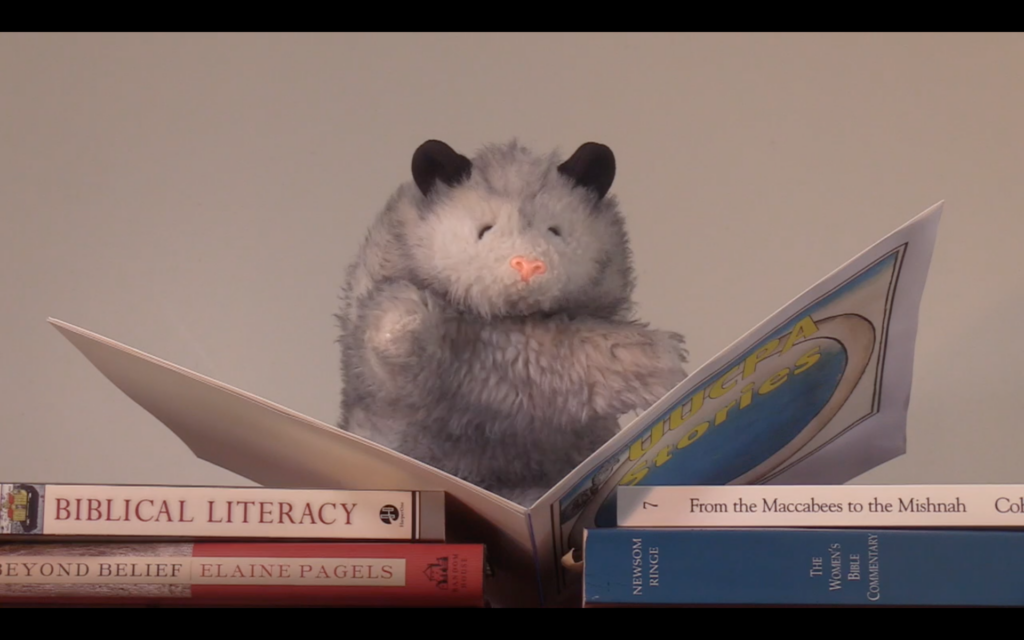

Yet even with these caveats, what Phil Benicasa said back in 2002 resonates with what I saw in a different educational setting, religious education in Unitarian Universalists, back in the late 1990s. But I was working with the same upper middle class predominantly White children that Benicasa worked with. To use a current catchphrase, I felt children in the late 1990s were often deficient in social-emotional learning. I don’t know why that was true, but it was.

Things have changed since 2002. I’m no longer in religious education, but I still see the same upper middle class predominantly White children that I’ve been working with since 1994. Up until the COVID pandemic, I felt that children became more able to fit in to structured social situations. Some of that change came from a bit more social-emotional learning, and some of it came from children simply becoming more compliant with authority.

I also felt that some of that change came at the cost of children’s mental and spiritual well-being. In the years leading up to 2020, I felt that I saw increasing amounts of depression and anxiety in children; at least, in the populations I worked with. Children had internalized the message that they need to do everything they can to gain (as Phil Benicasa put it) “a direct line to Harvard.” And, to quote him again: “That’s absolutely nonsense.” What you do in elementary school or middle school is not going to get you into Harvard.

Then the pandemic hit. The pandemic accelerated some of these trends. To succeed at online school, kids had to become even more compliant. And the rates of depression and anxiety went up even faster, as near as I could tell. But the pandemic also meant that children lost a lot of ground in social-emotional learning. We’re barely out of the pandemic, so it’s too early to know if children will regain that lost ground or not. The pandemic also meant that children stopped participating in extra-curricular activities that promoted social-emotional learning, programs like Sunday school. Participation in sports keeps rising, but while sports does tend to make children more compliant, in my observation it doesn’t do much to improve social-emotional learning.

The pandemic also accelerated a trend I’ve been watching when it comes to the spiritual development of upper middle class children. The upper middle class consists of the “cultured despisers of religion,” so spiritual development tends to be low on their list of priorities (spiritual development won’t get you into Harvard). The upper classes limit spiritual development to meditation, mindfulness, and yoga — which are considered worth doing because they allegedly help children tolerate stress better. Unfortunately, what I’ve seen is that meditation, mindfulness, and yoga mostly seem to work to make children more compliant. Nor do they address the root causes of children’s anxiety and depression; instead, they simply cover them over.

I’d like to say that Unitarian Universalist (UU) religious education would help advance children’s social-emotional learning, improve their mental health, and (instead of making them more compliant) help them discover who they are and what their purpose is. But I’m less than impressed with the way most UU congregations implement their religious education programs. Most of these programs today seem to be run for the convenience of the staff and the child-free lay leaders. As an example, think of the many UU congregations that set monthly themes for worship services, then force children’s religious education curriculum to follow those themes regardless of the developmental and educational needs of the children. The adults come first; the children are supposed to be quiet and comply with the needs of the adults. No wonder UU religious education enrollment has been plummeting in recent years.

I don’t have a happy little conclusion for this blog post, except to say I’m worried. I’m worried that the selfishness of Unitarian Universalist adults is driving children away. I’m worried about children’s mental health, and limited social-emotional learning. I’m especially worried about the way children are being make more and more compliant — this in a time when fascism is on the rise.

(See also this post on why Sunday schools are declining.}