The next installment of the Prometheus myth:

As usual, full script is below.

Continue reading “Prometheus, part two”Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

The next installment of the Prometheus myth:

As usual, full script is below.

Continue reading “Prometheus, part two”I’ve been looking for a way to extend our congregation’s asynchronous learning, and one of the online tools I’ve looked at is Padlet.com.

Padlet.com is basically an online interactive bulletin board. Some elementary school teachers use padlets to allow students to interact with a teacher presentation — kids can comment on teacher posts, and teachers can also allow kids to make their own posts. (An individual bulletin board is typically referred to as a “padlet.”) Some teachers also use padlets as parent communication tools.

I wasn’t excited or inspired by the gallery of examples on Padlet.com, but since it’s a free service, I thought I’d give it a try. It’s better than I thought.

While it’s hard to imagine that children or teens in a religious education program will voluntarily interact with a padlet — unlike elementary school teachers, those of us in religious education cannot complete students to use something with the threat of a bad grade — I feel that padlets could be useful parent communication tools, to help parents know know what’s going on in a class. I think padlets could work quite well to organize resources to share with adult education classes. And Padlet.com is fairly easy to use for volunteer teachers — there’s not much of a learning curve. Finally, Padlet.com is obviously better for a volunteer-run program like Sunday school than a learning management system like Google Classroom, which has a steep learning curve and requires domain email addresses for all users (who wants another email address?).

However, I don’t think Padlet.com offers much advantage over using existing tools — such as Google Drive — to organize resource materials and allow student interaction. I’m also annoyed because when I just logged on to a padlet I created for other religious educators, Padlet.com refused to display embedded content — see the screenshot below. This does not make me want to pay for a premium account, and if this is what end users are going to see, I’m definitely better off using a Google Drive folder. It also occurs to me that all my volunteers already know how to use Google Drive, and why should I make them learn how to use Padlet.com?

Maybe I’ll return to Padlet.com in the future, but at this point I’m not overly enthusiastic.

William R. Jones, UU theologian and one-time religious educator, pointed out may years ago that the myth of Prometheus serves as a useful counter to the myth of Adam and Eve. For Adam and Eve, rebellion is sinful; for Prometheus, “a response of rebellion is soteriologically authentic.” Although Jones considers the Prometheus myth to be important for humanists, I think Prometheus is important for anyone who is an existentialist — which means almost every Unitarian Universalist today, whether they are humanist existentialists, Christian existentialists, pagan existentialists, Buddhist existentialists,….

That means the myth of Prometheus should be an integral part of Unitarian Universalist religious education for kids. Here’s one attempt to make that happen, as several ordinary people go back in time to relive the myth o Prometheus:

Full script is below….

Continue reading “Prometheus, part one”Here’s the first short lecture I used in last night’s online class on Unitarian Universalist (UU) theologies:

For accessibility, the text of the lecture is below. Note that I may have altered the text a little when reading it.

Continue reading “UU theologies: Hosea Ballou’s Universalism”For an adult religious education class on Unitarian Universalist theologies, I recorded four short videos. I’ll get to the videos in a moment, but first, a word about online teaching….

Like so many educators, I’ve been trying to figure out how to adjust to our new reality of distance teaching. We feminists have criticized patriarchal pedagogy as disembodied; patriarchal education keeps everything in the head, ignoring the reality of the body. But how do you do embodied teaching when all you see are a bunch of tiny images of people’s heads on your computer screen? A great many pedagogical tools in my feminist-educator toolkit are useless in online learning.

I was talking over this problem with someone I have a great deal of respect for, a feminist who has been doing online teaching for a decade now — she moved to online learning because her subject area is quite specialized, with the result that her students are spread out over the entire North American continent. She said what has worked best for her is to record short videos, of under ten minutes, with lectures outlining a topic area; after showing one of the videos, she moderates an open discussion of the topic.

I’ve been teaching a biweekly adult religious education class — with mixed success — and I decided to try this approach for last night’s class. I was scheduled to teach an hour-long class on Unitarian Universalist (UU) theologies. I focused on four UU theologies, as exemplified by five different persons, prepared four short talks, and recorded four short videos. The class went reasonably well, from my point of view. While the videos were playing, I was able to monitor the chat in the videoconference call, and I could look at the video feeds (of those who left their video on) to monitor facial reactions. The videos were followed by a lively discussion — though with 21 log-ins, it was less than spontaneous, since everyone had to stay muted except for me and one person making a point or asking a question.

Making the video lectures took more time than I would have liked. Yet by recording these short lectures in advance, I could trim out all the times I coughed (with all the smoke in California, I’ve been coughing a lot), and if I stumbled verbally, I could trim or re-record the part where I stumbled. I could also clean up the sound while editing the video, and control the lighting and composition of the visuals.

Another benefit to pre-recording the lectures: I can post them online, where they’re accessible to people who were unable to attend (e.g., due to child care responsibilities). And I can re-use the videos to teach the same class in a year or so, because the discussion that followed the lectures will always be different; plus, with several short videos, I can record new videos on the same topic.

My final conclusion: Although this method of teaching is nowhere near as good as in-person teaching, it was still the best approach I’ve yet tried for online teaching.

In a subsequent post, I’ll include a link to one of the videos, followed by the text of the lecture.

A bunch of U.S. professors and scholars will stop teaching and attending to routine meetings today and tomorrow, in order to have a sort of “teach-in” about racial injustice in America. On the blog of Academe magazine, Anthea Butler and Kevin Gannon write:

“Scholar Strike is both an action, and a teach-in. Some of us will, for two days, refrain from our many duties and participate in actions designed to raise awareness of and prompt action against racism, policing, mass incarceration and other symptoms of racism’s toll in America. In the tradition of the teach-ins of the 1960s, we are going to spend September 8–9 doing YouTube ten-minute teach-ins, accessible to everyone, and a social media blitz on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to share information about racism, policing, mass incarceration, and other issues of racial injustice in America.” Link to full blog post.

It was Anthea Butler, professor of religious studies and Africana studies at UPenn, who started the whole thing with a tweet towards the end of August. I’ve been interested in her work for a while now: she keeps getting quoted in news stories I read, and she’s got a book coming out in the spring, White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America, that I’m looking forward to reading.

Butler and Gannon also acknowledge that many, perhaps most, scholars working in academia, will not be able to participate in the strike:

“We are also acutely aware of the precarity of most college faculty; many of our colleagues hold positions in which they cannot step away from their duties for a day or two, or are covered under collective bargaining agreements. It might seem odd to think of college faculty as “workers,” but the stereotype of the fat-cat tenured professor is not an accurate one. Indeed, 75 percent of all credit hours in US colleges and universities are taught by underpaid adjunct faculty, who not only lack the protections and benefits of full-time faculty, but are employed on a class-by-class, term-by-term basis. Even those of us in more secure positions still work on campuses where fiscal crises and a pandemic have combined to make everyone’s employment status precarious….”

And of course it’s a challenge to do this kind of teach-in when many students aren’t even on campus due to COVID — and of course, distance learning was already becoming the norm for many colleges and graduates schools, since distance learning is so much less expensive for the administrators to operate. Nor is it a coincidence that distance learning also makes it much harder to fan the flames of discontent among students.

Follow the strike live:

Scholar Strike Web site

Scholar Strike Youtube channel

Scholar Strike Facebook page

Twitter hashtag #ScholarStrike

Canadian Scholar Strike

News stories:

Inside Higher Ed article

Religion News Service article (emphasizes religion and theology scholars)

Possum and his friends act out the Sumsumara-Jataka (no. 208):

Full script is below the fold….

Continue reading “Jataka tale: The Monkey and the Crocodile”The final installment of the “Possum Feel Stressed” series of videos:

As usual, full script is below….

Continue reading “Possum feels stressed, conclusion”The fourth installment in this video series:

Full text of the script is below….

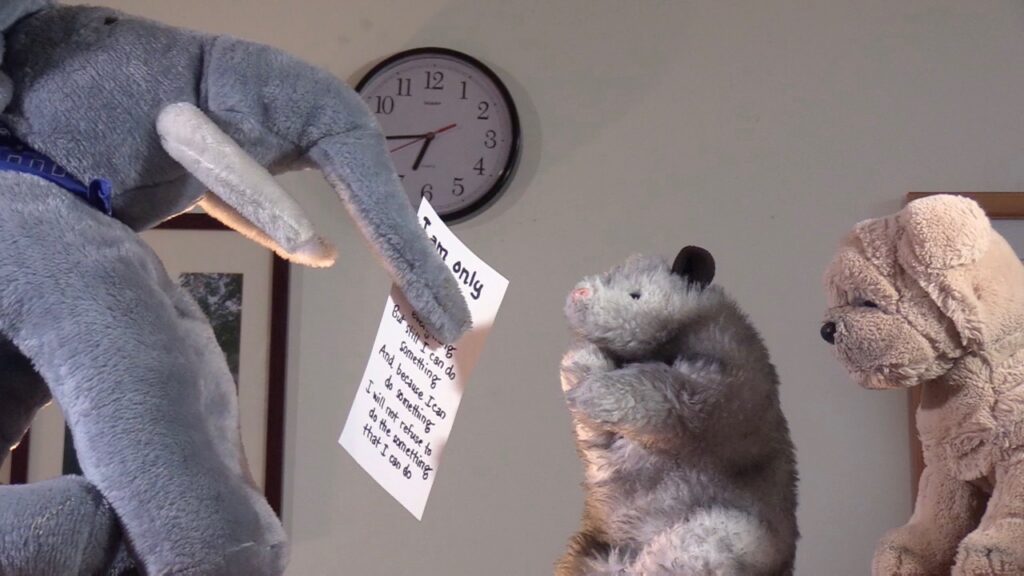

Continue reading “Possum is working on reducing his stress”In the third installment of the Possum Feels Stressed video series, Possum learns about prayer as a spiritual practice (even though he doesn’t believe in God):

The first poem mentioned in the video is by Edward Everett Hale, a Unitarian minister:

I am only one.

But still I am one.

I cannot do everything.

But still I can do something.

And because I cannot do everything

I will not refuse to do the something that I can do.

The second poem mentioned in the video is by Universalist poet Edwin Markham:

Outwitted

They drew a circle that shut me out —

Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took them in.

Full script for the video is below….

Continue reading “Possum is still stressed…”