Labor Day has come again — at least, the United States version of Labor Day.

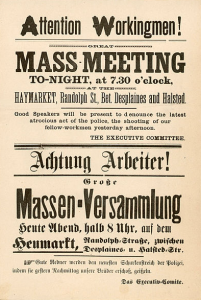

Everywhere else in the world, Labor Day is celebrated on May 1. But not in the United States. May 1, 1886, was the date of a general strike throughout the United States for the right to an eight hour day: “Eight hours for work, eight hours for sleep, eight hours for what we will.” In Chicago, the strike continued through May 3, where as many as 80,000 workers stopped work. Though the workers were peaceful, the police were not — on May 3, they fired on striking workers, killing at least two workers. So a mass rally was arranged for the next day, May 1, in Haymarket Square.

Police arrived in Haymarket Square at 10:30 p.m., just as Methodist minister Samuel Fielden was concluding a short speech, and as the peaceful demonstration was beginning to wind down. Police Captain John Bonfield, backed by a large contingent of armed police officers, ordered the already dispersing workers to disperse. Then someone threw a bomb, killing one officer and wounding several others. Police began firing at the workers, and also apparently at each other. Seven police officers were killed, at least some of them probably by friendly fire. At least four workers were killed, and over a hundred people total were wounded.

Eight people were convicted of the bombing, in a trial that almost all historians agree was a travesty of justice. In 1893, the governor of Illinois pardoned the three who hadn’t been executed, saying, “Capt. Bonfield is the man who is really responsible for the deaths of the police officers.”

But the damage to the labor movement had already been done. The Haymarket Massacre was all the excuse that employers needed to put an end to the call for an eight hour day. Corporations, newspapers, and politicians blamed the violence on immigrants and anarchists. The Chicago city government used the Massacre as an excuse to arrest scores of labor organizers. The massacre, which was acknowledged to have been incited by a police official, turned out to be a major setback for organized labor’s efforts to win an eight hour day for all U.S. workers.

The eight hour day finally became a reality — sort of — in the 1937 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which required about one fifth of U.S. employers to pay overtime if a worker had to work more than 40 hours in a week. Gradually, that sort of became the norm for most workers, and atually became the law in some states. By 1984, when I started working in a Massachusetts lumber yard (because there were no jobs for philosophy majors during a recession), we were required to work a 50 hour week, but at least we got paid overtime if we worked more than 40 hours in a week, or if we worked more than 8 hours in a day.

I continued to work hourly-wage jobs until 1997 when I got a FLSA non-exempt job. Of course, I just took the eight hour day and the right to overtime for granted. The story of the Haymarket Massacre, and the rest of the bitter fight for an eight hour day — no one told me that story. It’s the kind of story that gets people worked up, that makes them believe that their employers don’t have their best interests at heart, that makes them believe that they might deserve to have more control over their working life. But I didn’t know any of that. Labor Day took place in early September, not on May 1, and rather than commemorating the Haymarket Massacre, it was just a nice way to end the summer.

Today, the age cohort known as Generation Z has become very supportive of unions. No surprise there. Employers are paying less, finding ways to ignore labor laws, and generally treating workers like they’re disposable. Many in Gen Z have realized that their most viable path to a middle class life is through unionizing. Maybe Labor Day can become more than an end to summer — maybe it can become a celebration of Gen Z’s unionization efforts.

And as we celebrate another U.S. Labor Day, perhaps some members of Gen Z will join me as I hum to myself — quietly, so as not to disturb our corporate masters — an old song that still seems to resonate today: “The Commonwealth of Toil” by Ralph Chaplin, hummed to the tune of “Nellie Gray”:

In the gloom of mighty cities, amid the roar of whirling wheels,

we are toiling on like chattel slaves of old.

And our masters hope to keep us, ever thus beneath their heels,

and to coin our very life blood into gold.

Chorus: But we have a glowing dream of how fair the world will seem,

when we each can live our lives secure and free.

When the Earth is owned by labor, and there’s joy and peace for all,

in the commonwealth of toil that is to be.

They would keep us cowed and beaten, cringing meekly at their feet.

They would stand between the worker and their bread.

Shall we yield our lives up to them for the bitter crust we eat?

Shall we only hope for heaven when we’re dead?

They have laid our lives out for us to the utter end of time.

Shall we stagger on beneath their heavy load?

Shall we let them live forever in their gilded halls of crime,

with our children doomed to toil beneath their goad?

When our cause has been triumphant, and we claim our Mother Earth,

and the nightmare of the present fades away;

we shall live with love and laughter; we, who now are little worth,

and we’ll not regret the price we’ve had to pay!

(as learned from the SF Labor Chorus)