We had our annual singing of “God Rest Ye Unitarians” yesterday, best known for its refrain of “O, tidings of reason and fact, reason and fact….” Several people asked for copies of this parody Christmas carol. Here it is, with music based on an 1846 SATB arrangement by Rimbault (click on the image below for a full-size score):

Who’s a member? (What’s a member?)

Three of us from our congregation met this afternoon to talk about our new membership database. The topic for today’s conversation: what categories will we have for people in the database?

Twenty years ago, it was fairly easy to categorize people in your congregation’s database: there were members, and there was everyone else. Members were those people who signed the membership book (in my religious tradition, some people used to get theological and defined members as those who agreed to abide by the congregation’s covenant). Most people who attended your congregation’s Sunday services on a regular basis would sign the membership book, sooner or later. Sure, there were always one or two grumpy people who refused to become members; and a few conscientious people who, for reasons of (carefully thought out) conscience, felt they could not sign the membership book; but most regular attenders eventually became members.

That was twenty years ago.

Today, fewer and fewer people seek out institutional affiliation of any kind. Probably this is related to larger societal trends of civic disengagement, the loss of trust in all institutions, and the displacement of organized religion to society’s margins. In a new book, congregational expert Peter Steinke says, “None of this has to do with the church’s internal functioning. The sea change is external or contextual.” Whatever the cause(s), we’re seeing more and more people who want to participate in our congregations without ever wanting to become members.

In the near future, I predict that “membership” is going to attract an ever decreasing number of people.

The problem is, we knew what to do with members. The congregation sent its members regular communications (e.g., newsletters, email lists, etc.), which they liked to receive, and which they read. They in turn knew how to communicate with key people in the congregation. And both the congregation and the members knew who was going to ask for money to run the congregation, and where that money is coming from.

We still know what to do with members, but we’re not quite so sure what to do with the other people who are coming into our congregations, the ones who don’t want to become members. These people may not want to receive our newsletter — they only want to hear about the things they want to hear about; and they want to hear about them in the ways they prefer (SMS, Facebook), not the ways we prefer (printed and email newsletters). These people do not know what a canvass is, or how or why we raise money (some of them even think we receive government support — no joke!), although they’re probably willing to be educated about how we take care of our finances, and how they can help us further our mission.

These are some of the things the three of us talked about this afternoon. We came up with at least four categories for our new membership database: “members” (people who have signed the membership book and who pledge annually); “friends” (people who have signed a declaration of friendship, a lower level of affiliation); “participants” (people who have participated in one or more congregational activities, ministries, or events); and “newcomers” (people who have showed up Sunday morning and are still relatively new to our community). We talked about the idea of another category, which we tentatively called the “distance” category: those people who no longer live close to us but who feel an emotional attachment to us, who may want to receive our communications, and who may sometimes want to give money to as a tangible expression of their appreciation for the congregation. We toyed with the idea of having separate “participant” categories, one for Sunday mornings “participants,” and one for “participants” who come at other times, but decided we don’t need that level of detail (yet). We did add a category for “child,” because we needed to distinguish between adult “participants” and non-adult “participants.” We also added a category for “deceased.” And we talked about other ways people may have relationships with our congregation, which we don’t quite know how to describe or categorize as yet.

I came away from our meeting with a very strong sense of the increasing importance of types of congregational affiliation besides “membership.” More and more people care less and less about the meaning of “membership,” and the younger they are the less they care. It’s like a century ago, when gradually people didn’t want to own pews any more, and they came up with this idea of congregational membership instead. Well, just as pew ownership once disappeared, I suspect we’re seeing a time when “membership” is slowly disappearing.

What do you think — is congregational membership is slowly disappearing? If so, what do you think will replace it?

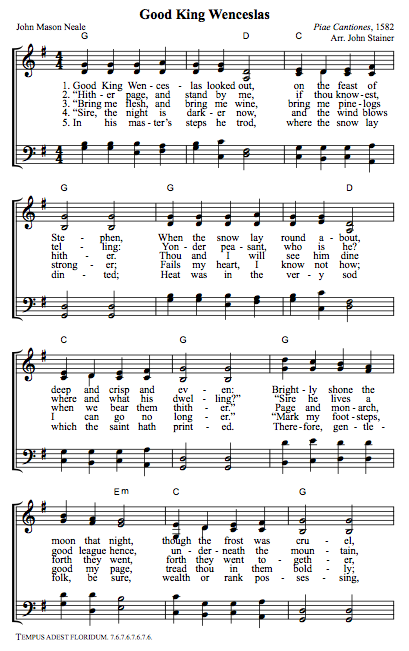

Good King Wenceslas

Here’s another song for Christmas time:— Quite a few people in our congregation like the song “Good King Wenceslas” because it’s a social justice song: King Wenceslas and his page bring food, drink, and fuel to a poor family on the Feast of St. Stephen, December 26 (the second day of Christmas). While they’re trudging through the snow to the poor family’s dwelling, the king’s page weakness and thinks he can go no longer, but Wenceslas provides warmth to keep him going; and this is my favorite part of the story because it seems to me to be a kind of parable about social justice leadership.

Philip, a long-time member of our congregation, pointed out to us that you can produce a nice effect if the high voices (i.e., most of the women and the children) sing the page’s words, and the low voices (i.e., those who sing in the tenor and bass range) sing the king’s words. So that’s how we sing it in our congregation.

Click on the image below for PDF sheet music of the traditional (copyright-free) four-part arrangement by John Stainer, with guitar chords, and sized correctly to fit into the typical order of service:

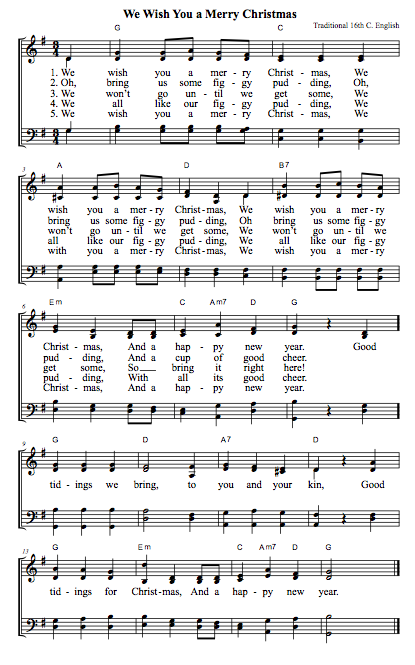

“We Wish You…”

Every year in our congregation, Paul, one of our resident musicians, teaches the children in grades preK – 3 a couple of Christmas songs. On the day of our No-Rehearsal Christmas Pageant, Paul has the children sing these songs at the beginning of the early service.

One of the songs Paul usually has the children sing is “We Wish You a Merry Christmas.” Actually, it’s a great song for anyone to sing. I found an old four-part arrangement, simplified it, added guitar chords — and here it is, in a PDF version that’s copyright-free and sized right to go into the typical order of service:

“Full Week Faith” or “Will There Be Faith?”

I’ve just been checking out Karen Bellavance-Grace’s white paper “Full Week Faith: Rethinking Religious Education and Faith Formation Ministries for Twenty-First Century Unitarian Universalists.” If you read it, I think you’ll find that this paper is a pretty good summary of the debates that have been going on within Unitarian Universalism regarding the role of religious education. And that’s both a strength and a weakness. It’s a strength because Bellavance-Grace summarizes the debates nicely, and offers a positive way forward. It’s a weakness because the Unitarian Universalist conversation on religious education has gotten pretty narrow, and has not paid attention to a wider international, interfaith conversation about the role of religious education.

While reading Bellavance-Grace’s paper, I’ve also been reading Thomas Groome’s latest book, Will There Be Faith? and it’s worth making a brief comparison of the two.

Both writers are committed to religious education that is grounded in the experience of learners. But Groome goes further than Bellavance-Grace, and he says that it’s not enough talk about “experience,” because that doesn’t do full justice to the ability of learners to take charge of their own learning. Drawing on Paolo Friere’s work, Groome says he prefers the word “praxis,” by which he means real-world practical action that is more than social service or band-aid charity. As a left-wing Catholic, Groome stands to the left of Bellavance-Grace, particularly in his insistence that children should be active participants in their own learning, and in his insistence that doing education with children can (and should) effect real change in the wider society. So it’s great that Bellavance-Grace continues to be committed to the tradition of experience in education, as set forth by John Dewey a century ago, and it’s great that she updates it for the postmodern era. But Groome is in that same tradition, and he elaborates on Dewey using the insights of Paolo Friere, and then he takes it even further using his own shared praxis model. I find Bellavance-Grace to be a little too conservative for my tastes; Groome’s insistence of the preferential option for the poor, his insistence on the need to seriously challenge the world around us — I find these more in line with what my religious convictions demand of me.

Both writers are committed to educating children into a faith tradition. Groome explicitly acknowledges the insights of John Westerhof, who, at the first rumblings of postmodernism in the 1970s, was one of the first religious educators to point out the new need to explicitly teach children how to be a part of a faith tradition. Bellavance-Grace does not explicitly acknowledge Westerhof, but his influence is clear on her work. Both Bellavance-Grace and Groome come up with similar pedagogical approaches to educating children in faith — Bellavance-Grace calls her approach “experilearn,” and Groome calls his “life to Faith to life.” — and both these approaches emphasize the connection between the life of faith and the rest of the world. But Groome’s pedagogy is much more fully developed, and has a more practical orientation. Also, because his pedagogy is grounded in Friere, there’s a much stronger sense of how reflection and praxis are intertwined; you don’t just learn something then move on, you engage in the world, reflect on your engagement, then engage again, reflect again, and so on for a lifetime. Since I’m a working religious educator, I find Groome’s practical and more fully developed pedagogy to be far more useful.

So Bellavance-Grace and Groome are pretty close in terms of their educational philosophy, and either or both would be useful to Unitarian Universalist parents and religious educators. Unfortunately, many Unitarian Universalists will be turned off by Groome simply because he is a Christian and a Catholic; so many Unitarian Universalists still wear the blinders of anti-Christian and/or anti-Catholic prejudice (and I’ve never quite understood why John Roberto gets a pass from Unitarian Universalists when other Christian religious educators don’t). But while Bellavance-Grace’s paper is quite useful, I think she just doesn’t go far enough; and in the end she advocates a kind of top-down approach driven more by religious professionals than by parents and kids. Groome’s shared praxis approach takes us beyond John Dewey; I think he has a better grasp of the postmodern context; he offers lots more sound practical advice, advice for the grass-roots which will work for religious professionals, parents, and even for kids.

Yes, Bellavance-Grace represents state-of-the-art Unitarian Universalist religious education; she has nicely distilled current cutting-edge Unitarian Universalist religious education practice. The problem is that Unitarian Universalist religious educators are behind the times, and if we want to catch up, we’re going to have to look beyond our narrow borders.

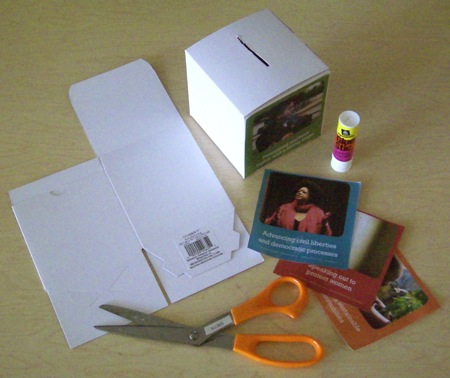

Pushkes and the UUSC

Amy, the senior minister at our church, had to tell me what a pushke is. “Pushke” is a Yiddish word for a little box that you keep in your house into which you can place money that is to be donated to charity. I didn’t grow up Jewish, and we just called them money boxes; but I think pushke is a much better word.

Up until this year, the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee used to send out little boxes to support their Guest at Your Table program. Every year on the Sunday before Thanksgiving, families would come to Sunday services, pick up their Guest at Your Table box — their Guest at Your Table pushke, if you will — and bring it home to put on their kitchen table. Then during the weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas or New Year’s Day, kids were supposed to put a little money in the box each day. Towards the end of December, families would count up the money they had deposited in the box and the grown-ups would add something to round it up to the nearest ten or twenty dollar mark. On the Sunday before Christmas, all the families would bring their pushkes full of money to be collected at the service, and the congregation would send it all to the UUSC.

This year, the UUSC decided it wasn’t going to send out Guest at Your Table boxes any more. I can understand why they made this decision. Each of those boxes must cost the UUSC a dollar or so; better to spend money on helping people, rather than on Guest at Your Table boxes.

However, I found an interesting informational paper written by Jennifer Noparstak, a graduate student of social work at the University of Michigan. She writes that in the Jewish tradition, pushkes help teach young people about giving and philanthropy. Pushkes teach the importance of anonymous donations: “Anonymous donation maintains a dignified relationship between those who are giving and those who are receiving aid.” Pushkes teach the importance of community in giving: “[The pushke] is also important because it signifies a community effort to aid people who need it and may not be able to ask for it directly. The pushke serves as a means for each member of a household to contribute, both children and adults alike, fostering the importance of giving among all age groups.” And, perhaps most importantly, pushkes cultivate the habit of charitable giving: ” It is considered more credible to develop a habit of giving regularly rather than giving large sums infrequently.”

Here in our congregation, we decided that even though the UUSC isn’t going to make Guest at Your Table boxes any more, it was important for us to provide Guest at Your Table pushkes for our families. Our Guest at Your Table Coordinator, Beth Nord, found plain white gift boxes that are the same size as the old Guest at Your Table boxes (look for 4x4x4″ gift boxes, sometimes sold as gift boxes for coffee mugs; Beth bought ours at Michaels, an arts-and-crafts chain store). We printed out images from the UUSC, sized so they would fit onto the sides of the pushkes — like this:

You cut out the four pictures, take one of the plain white gift boxes, glue one picture to each of the four sides, cut a slot in the top for money, and there you have it — your very own Guest at Your Table pushke. Here’s one in the process of being made:

This morning during the service, Amy explained where the Guest at Your Table money goes to, while I showed how to make a pushke. After each service, kids came with great enthusiasm to pick up boxes and pictures to take home so they could make their own pushkes. This is the most enthusiasm I’ve ever seen for the Guest at Your Table program!

So the UUSC gets to save money, our kids are more enthusiastic about the Guest at Your Table program, and we continue to provide pushkes to help teach kids about giving anonymously, giving communally, and getting in the habit of giving a little bit every day to charity.

Academics and practitioners

A few days ago on the “Key Resources” blog, a blog about faith formation from Virginia Theological Seminary blog, Kyle Oliver asked: “What has the academy to do with congregational faith formation (and vice versa)?”

What prompted this question? Kyle had been at the recent annual conference of the Religious Education Association (REA), which is supposed to be an organization of scholars and practitioners. But he had not been convinced that the REA offers much to practitioners: “I wasn’t entirely convinced of the value of the conference for a non-academically-aspiring faith formation minister in a congregation.”

Speaking as a minister of religious education, I agree with Kyle that the academics, not the practitioners, dominate the conference. Two examples of what I mean when I say the academics dominate: (1) At the 2011 conference, I went to an excellent workshop given by Ryan Gardner on teacher reflection for volunteer teachers; it was the only practical workshop in that time slot; yet only two other people showed up, one of whom admitted she was in the wrong workshop (she stayed anyway, bless her heart). (2) At this year’s conference, I went to a good workshop given by Tom Groome on practical approaches to pedagogy for the local congregation; again, it was the only practical workshop in that time slot; yet the conversation got taken over at a couple of points by academics who wanted to argue rather obscure theoretical points. At the same time, all the academics whom I met were sympathetic to practitioners; some of them appeared to be pleased when they found out I actually worked in a congregation with real, live children and youth. I don’t think the academics want to dominate the REA conference.

Some of the problem may lie in the realities that we religious education practitioners face these days. When I started working as a religious educator in the Boston area, back in 1994, it was commonplace for some of the older religious educators to talk about how they studied with Robert Kegan, James Fowler, Tom Groome, and other scholars. Back then it was also commonplace for lay Directors of Religious Education to have a full-time, well-compensated job; there were many more Ministers of Religious Education; congregations expected us to take time to study and keep up with the field. That’s no longer true. As staff costs for congregations outpace inflation, as organized religion declines in an era of civic disengagement, as society changes rapidly around us, as congregations need more from us and are able to offer less to us — as all this goes on, many of us who work in local congregations feel overwhelmed as we try to do more and more with less and less, as we try to keep kids engaged, as we try to hold on to our jobs and our pay.

As a result, when we practitioners go to any kind of conference, we’re usually looking for relentlessly useful ideas that we can use right now. We’re desperate. John Roberto of Faith Formation 2020 gets this; he gives us practitioners what we need in easily digestible bites. At the recent REA conference, I think Beth Katz of Project Interfaith intuited some of this; she showed us excellent and innovative curricula that were both immediately useful and grounded in interesting theoretical perspectives. Mind you, Katz and Roberto are not exactly academics, though they are academically informed. One academic who gets this is Bob Pazmino: I talked with Bob informally at the recent REA conference, and he not only asked me about what was going on in my congregation, and listened carefully and respectfully, but he was able to present me with some interesting possibilities for new directions based on his academic work.

In short, I think Kyle Oliver is correct when he says that he’s not “entirely convinced of the value of the REA conference” for most of us practitioners. I think the academics might want to pay more attention to Kyle’s critique, and think about how they might better unite their theory with our practical realities.

I would also say that we practitioners have to remember that our praxis should be informed with theory. Perhaps it’s time to get a little more assertive, as Kyle is doing, and help the academics pay better attention to what’s going on in our local congregations.

Happy (belated) National Adoption Day

Yesterday was National Adoption Day, a day to celebrate those people who adopt children for all the right reasons. I’m thinking especially of M. and O. who are in the adoption process right now. Adoption can be a long process, with lots of bureaucratic hurdles. All those hurdles are designed to protect the interests of the children, but they sound like very challenging hurdles to me. I have a lot of admiration for those good-hearted adults who are willing to jump those hurdles, and welcome deserving children into loving homes.

So here’s to you, adoptive parents!

Perry Mason checklist added

I’ve added a page to my Web site, a checklist of Perry Mason novels and stories, and you can find it here.

Snow and dialect

On the last morning of my trip back east, it started snowing. I hadn’t seen snow falling for more than four years, not since we moved to the San Francisco Bay area. I got that familiar, mesmerized, contemplative feeling that you get when you watch snow falling; and almost immediately the worry kicked in: will this affect driving? will my flight be delayed? are my shoes waterproofed? Fortunately the snow stopped after about ten minutes, leaving no accumulation: I got the pleasure of seeing it without all the discomfort that goes along with snow.

While I was in the Boston area, it was interesting to again speak in what the linguists call Eastern New England dialect — popularly known as a “Boston accent,” though really there are several Boston accents which are a subset of Eastern New England dialect, and actually my accent is west of Boston, with a does of New Bedford from my time living there. Whatever my accent, or the accent of the natives I talked with, I found it’s much easier for me to communicate when speaking Eastern New England dialect, and I realized I always feel there’s always something missing when I have to speak American Standard English, that bastard dialect of television and movies that lacks subtlety and emotional nuance.