I’ve been working on developing a curriculum for upper elementary children. The basic idea comes from the old Beginnings: Earth, Sky, Life, Death curriculum developed in the mid-twentieth century by Sophia Fahs. However, much of the content is new, the theological framework has been updated, and the curriculum has been designed to be extremely user-friendly. And now almost the entire curriculum is online for you to use — but before I get to that, let me tell you about several key features of this curriculum.

First, much of the content is completely new. I have included some of the stories from the old “em”Beginnings book, but I have always gone back to primary sources and/or scholarly commentary, and written these stories from scratch. I have also included completely new material, such as the story from the Yoruba tradition — a religious tradition that wasn’t even recognized by most Westerners when the old Beginnings book was written.

Second, the theological framework has been updated. Many UU curriculums of the past have been rightly criticized for assuming that all other religions are not as “advanced” as Unitarian Universalism; this curriculum attempts to avoid that trap of neo-colonialism. A companion curriculum is in development that will present Unitarian Universalist myths and stories in exactly the same way that these stories from other religions are presented. This curriculum also assumes that the possibility of significant diversity, of children coming from multi-religious households; i.e., the children in this UU Sunday school class might also have household members or close relatives who participate in another religious tradition such as Hinduism, Yoruba traditions, Judaism, Christianity, Chinese popular religion, etc. Thus I have tried to avoid any implication that another religion is less “true” or less important than our own religion.

This curriculum is also designed to provide some foundation for our version of the old “Church across the Street” curriculum, in which middle schoolers visit other faith communities. Thus, in some of the sessions, reference is made to religious practices that are related to the story for that session, to relate the mythic or narrative dimension of a religion with the ritual dimension (to use two of Ninian Smart’s seven dimensions of religion). Additionally, the illustrations include some photographs of the material dimension of religion.

Finally, and most importantly, the curriculum is designed to for today’s volunteer teachers. Sunday school teachers today need a curriculum that they can pick up ten minutes before class, and teach successfully with little or no prep time. At the same time, some experienced teachers may want the possibility of going more deeply into the lesson. So this curriculum is designed to provide maximum flexibility for teachers. After two years of use in our congregation, teachers seem to like the curriculum pretty well.

By putting this curriculum online, my goal is to make the curriculum even more user-friendly. The Web site uses responsive design, so that the curriculum will display equally well on a smart phone, tablet, laptop, or even a Web-enabled TV. No need for a book or a three-ring binder: all you need is your smart phone (though the illustrations will be easier to show to kids on a bigger screen). Having the curriculum online should also make it much easier for teachers to let parents know what children are doing in Sunday school.

I would love to hear your comments and reactions to this curriculum.To look at the online version of this curriculum, go here.

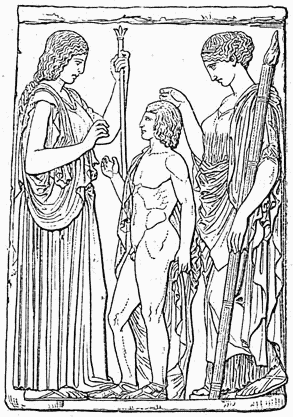

An illustration from the curriculum:

A statue of Obatala, an orisha common to many of the Yoruba traditions. This statue was photographed in Costa do Sauipe, Bahia, Brazil. Public domain photo from Wikimedia Commons.