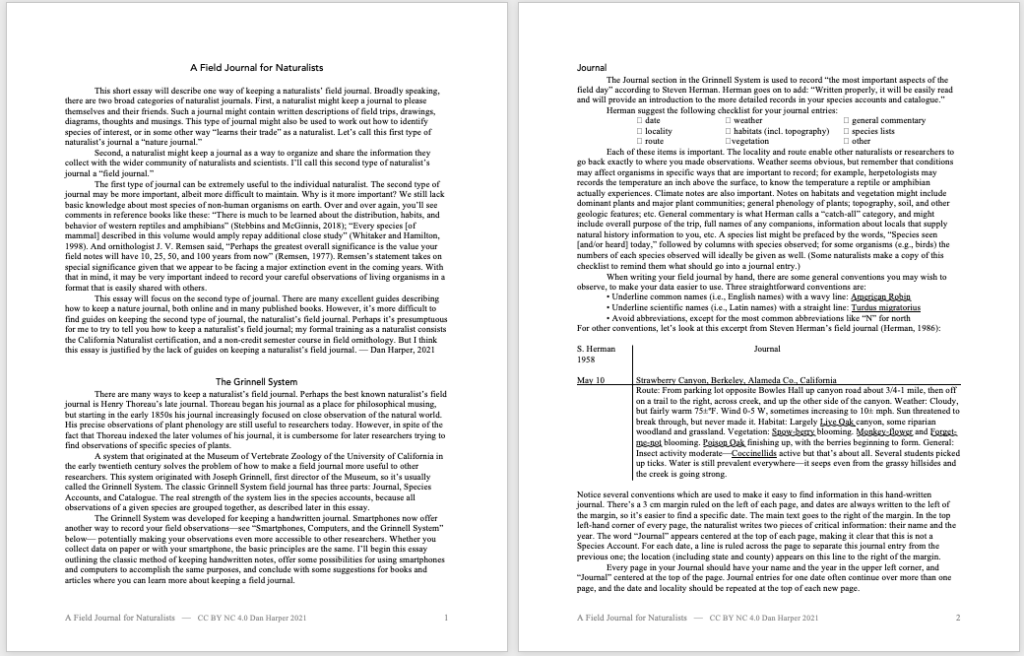

We’ve been singing “Follow the Drinking Gourd” with campers at our ecojustce day camp. But Tobi just pointed out that we may want to drop it next year. Why? Well, first of all there’s serious doubt whether it’s a traditional African American song. The most familiar form of the song (including the version found in the Unitarian Universalist hymnal) derives from the version recorded by the Weavers. This version is an arrangement by Lee Hays, first published in 1947 in “People’s Songs Bulletin”; let’s call this the Hays version. Compare the Hays version to the first published version, collected by amateur folklorist H. B. Parks between 1912 and 1918, which first appeared in print in 1928 in Publications of the Texas Folklore Society, Number VII:

The 1928 Parks version, with 11 measures and four fermata, does not conform to the conventional structure of Anglo-American folk music. The 1947 Hays version, on the other hand, has 8 measures with no fermata and a more elaborate melody in measures 5-6. You can imagine Lee Hays regularizing and developing the melody so that it better conformed to the standards of an eight-bar chorus of the Folk Revival. The Parks version, with its “irregular” structure, feels more like something that could have been collected in the field from a singer who had no training in conventional Western music theory. (And I admit my personal preference: I like its lonesome sound much better than what I consider to be the sanitized sound of the Hays version.)

But what about Parks’s version? How authentic is it?

Continue reading “Another attribution problem”