I awakened sometime in the middle of the night, and had a hard time getting back to sleep: too much caffeine too late in the day. So I listened to the freight cars in the railroad yard behind the hotel. As the cars were moved around the yard, their wheels gave off flute-like, almost musical, tones. First a tone held for three long beats, the basic tone of which was maybe as high as the C above middle C; then it would change in pitch, shifting suddenly to a higher note or notes. I began listening to the change in pitch, using standard solmization syllables to determine the rise in pitch. Do, re, mi, no not quite mi; a slightly flatted third, like the blue notes in jazz or blues. Do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti; that’s a major seventh. The notes began to blur into each other, there were chords, I was fast asleep.

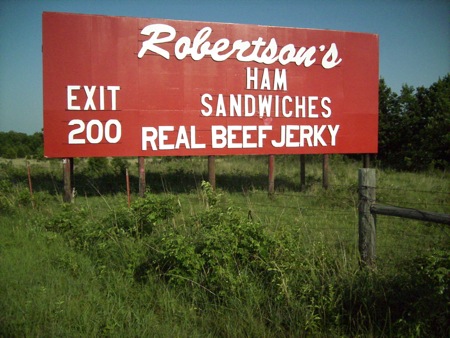

The next morning, we took a long walk along the Historic Route 66 in Barstow. The sun was incredibly bright, the air clear and very dry, and because it was so dry we didn’t feel uncomfortable walking through the desert heat. We went down a short side street where there was a big sign that read “Barstow Classification Yard,” and another sign that read “BNSF Barstow CA.” Carol stood around waiting while I took some photographs of the rail yard beyond. We walked past that, taking photographs of the motel and restaurant and other signs next to or on buildings along the highway: “Palm Court American-Chinese Food”; “Yahweh Flooring”; “Entrance /Low Rates / Office,” with an arrow pointing, and a Hindu “Om” symbol; “Route 66 Motel / Vacancy / Free WiFi — Round Beds — HBO — Remodeled Rooms — Best Prices”; “Robertiroz Mexican Food / Open 24 Hours 7 Days a Week.”

On one side of the highway, side streets led to neat modest homes; on the other side of the highway, beyond the Barstow Classification Yard, we could sometimes see the desert. If this strip of highway, with its big bright signs and bright gaudy roadside architecture, was anywhere else, it would have looked gaudy. But the highway was competing with the intense desert sun, and the glare, and the hot dry air, and it was no competition at all for the sun and glare and dry air won handily.

Driving west, we climbed up towards the Tehachapi Pass, through the high desert with Joshua trees here and there on either side. Erle Stanley Gardner, in one of his detective books, writes about driving through the desert at night and seeing “the weird Joshua trees on either side”; they do look weird, they look vaguely humanoid, but to me they have a friendly and very satisfying look to them.

Once in Tehachapi, the humidity set in. Visibility dropped, distant hills looked blue, the most distant ones disappeared in the haze, and I kept wanting to polish my glasses so I could see again. We began feeling the heat more. All during the long drive through the Central Valley, the air was blue with humidity, and the heat felt uncomfortable, even in the air-conditioned car. Finally we wound through the Coastal Ranges, and arrived at home near the shores of San Francisco Bay, where at last the air felt cool and comfortable.

from July 2, posted July 3