We planned to meet Carol’s cousin for dinner; that left us with the rest of the day to spend in Montgomery.

We went to the Rosa Parks Museum and Library, which is part of Troy University in Montgomery. The museum has a well-designed exhibit that tells the story of the Montgomery bus boycott through artifacts and creative audio-visual displays. The audiovisual presentation on Rosa Parks’s refusal to get out of her seat on the bus was especially good: it told and showed enough so you could follow along even if you didn’t know much about Rosa parks, but it left enough not told and not shown so you recreate the story in your imagination, which is what really makes it come alive.

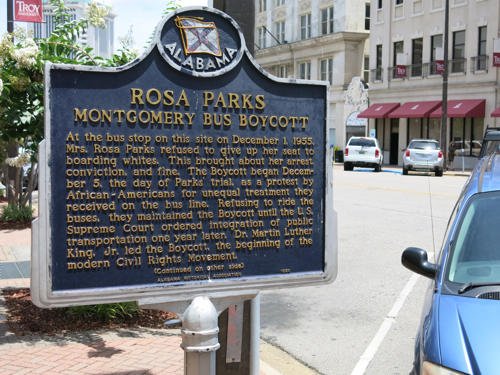

Out in front of the museum is a historical marker that reads:

“At the bus stop on this site on December 1, 1955, Mrs. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to boarding whites. This brought about her arrest, conviction, and fine….”

There isn’t much except the marker to remind you of 1950s Montgomery: there’s no longer a bust stop, the sidewalks are different, all that’s there is that historical marker with some words on it.

I wanted to walk up towards the Capitol building to see the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, and Carol was willing to go along. You couldn’t get near the church; the whole city block was closed to pedestrian traffic because Oprah Winfrey was filming her movie “Selma.”

A couple of white guys with cameras were standing there talking. “Last night they let me walk up to the church,” one of them said. He had a fancy-looking digital single lens reflex camera on a monopod. “They changed the name on the church to the original name” — that is, to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church — “and on the sign board it said, ‘Sunday morning, Dr. Martin L. King preaching.’ I got some good shots of that. But now they’re not letting anyone in.”

Small buses rolled in regularly. Extras in 1950s-era clothing walked from each bus into the Dexter Avenue Baptist church. A middle-aged black woman came up and cheerfully asked when Oprah was going to show up. Someone said she was going to be there at 5:30. We hadn’t seen any stars; all we had seen were extras.

I got to talking with the man with camera on the monopod. He pointed out his church, in the next block down, the River City Methodist Church. He said that they had gotten down to four members, when the bishop stepped in and settled a dynamic young pastor there. This pastor, said my friend, got rid of the organ music, brought in a praise band, started a thrift store, reached out to the homeless population in downtown Montgomery, and in less than a year had gotten the membership up to 65 people. My friend with the camera was the drummer in the praise band. “We’re Methodist in name only,” he said. “I was a Baptist, but they chased out the pastor of my church, just when River City Church was looking for a drummer. My sound guy used to be a Pentecostal, and I’ll look out when I’m playing and he’s there with his arms in the air. We’re from all different backgrounds. Our pastor says, ‘Church is not inside this building, church is out there, everywhere.'”

We left Montgomery to visit Catherine Coleman Flowers, someone Carol had met through her work in ecological wastewater management. Catherine was born in Lowndes County, Alabama, one of the poorest counties in the state, and is now the executive director of Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise (ACRE), a non-profit devoted to environmental justice. Catherine told us about a study recently conducted by ACRE that discovered evidence of hookworm in close to half of the stool samples they tested. This is a remarkable study because hookworm was supposedly eradicated from the United States in the early twentieth century. Yet people who live in poverty in rural areas may not be able to afford to install adequate wastewater management systems.

Plus, because of global climate change, Catherine believes that hookworm may find the South a more congenial place to live these days. Here is a serious issue linked to global climate change that cannot be solved through installing solar panels and purchasing fuel efficient cars — the solution will involve a combination of economic justice, economic development, and ecological justice involving decentralized wastewater management solutions.

If Rosa Parks were alive today, I’ll bet she’d be involved in environmental justice.