Kuan yin (in Pinyin, Guanyin) is a deity with multiple identities, including multiple gender identities. According to the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha said, “If living beings in this land must be saved by means of someone in the body of a Buddha, Guanshiyin Bodhisattva will manifest in the body of a Buddha and speak Dharma for them.” And if someone needs to be saved by this boddhisattva, Guanshiyin, who is also known as Guanyin or Avalokiteshvara, will manifest him/herself in whatever form works best:

“If they must be saved by someone in the body of the wife of an Elder, a layman, a minister of state, or a Brahman, he [sic] will manifest in a wife’s body and speak Dharma for them. If they must be saved by someone in the body of a pure youth or pure maiden, he will manifest in the body of a pure youth or pure maiden and speak Dharma for them. If they must be saved by someone in the body of a heavenly dragon, yaksha, gandharva, asura, garuda, kinnara, mahoraga, human or non-human, and so forth, he will manifest in such a body and speak Dharma for them.” [trans. from City of Ten Thousand Buddhas Web site

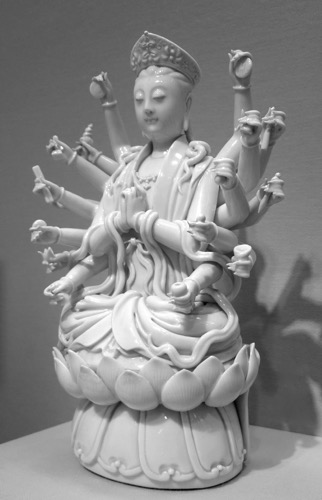

Above: “The Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Chinese: Guanyin), 1300-1400 CE,” Asian Art Museum, catalog no. B61S37+

Guanyin also became a Daoist deity, a female immortal; one can chant a spell to the Daoist Guanyin “whereby one will accomplish unimaginable virtues, and give evidence to the penetration of the absolute.” (Guanyin mizhou tu)

Above: A Daoist Guanyin, adapted from Henrik Sorenson’s article “Looting the Pantheon.”

“The increasing Daoist appropriation and transformation of the Avalokiteshvara cult and the associated teachings which took place during the later imperial period, is also reflected in the mid-Qing work, the Guanyin xin jing bijue (‘Secret Explanation on the Heart Scripture of Avalokiteshvara’). This text, which to all appearances and purposes appears to be a Buddhist commentary on the Prajnaparamitahrdaya sutra, one of the most important and popular Buddhist scriptures in China, on closer examination turns out to be a Daoist commentary on the Buddhist sutra. In addition to its full-scale doctrinal modification, it casts Avalokiteshvara in the role as a female immortal (nuxian) from the Zhou dynasty (1122–255 BCE). … the level of appropriation [of Buddhist deities by Daoism] could, and often did, go well beyond superficial borrowing, ending with something akin to full-scale integration.”

— Henrik H. Sørensen, “Looting the Pantheon: On the Daoist Appropriation of Buddhist Divinities and Saints,” The electronic Journal of East and Central Asian Religions, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Asian Studies at the University of Edinburgh, 2013), p. 62.