Taejonggyo, a new religious movement in Korea, worships Tan’gun, the legendary founder of the first Korean kingdom. The contemporary expression of Taejonggyo was founded in 1909 by Nach’ol, a Korean nationalist who was resisting the Japanese occupation of Korea. Nach’ol said that Taejonggyo had been the religion of Korea for some three thousand years before the importation from China of the foreign religions of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism during the Mongol invasions of the 13th century (Don Baker, Korean Spirituality [University of Hawai’i: 2007], pp. 118-119).

“Taejonggyo (The Religion of the Great God) … claims that Tan’gun, the legendary founder of Korea, is the original founder of Taejonggyo, which was revived by Nach’ol in 1909. It claims that it embodies the national spirit and philosophy. Tan’gun is believed to be the god-man and the founder of Korea, and he is the object of worship in Taejonggyo. Taejonggyo was at the forefront of the anti-Japan independence movement during Japnese colonialism in Korea. As a result, its followers were persecuted severely by the Japanese authorities.” Oliver Leaman, Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Routledge: 2006), p. 383.

Tan’gun is linked to National Foundation Day, or Gaechenonjeol, in South Korea: “Gaecheonjeol was made an official South Korean national holiday in 1909. The day is typically celebrated with public ceremonies, performances and speeches; government offices and many schools and private businesses are closed. … Ceremonies are held to honor Dangun [Tan’gun] at an altar of rocks he built at Chamseongdan, located at the top of Mount Mani…” (Korea Ye Web site). According to historian Don Baker, National Foundation Day was originally established by the Taejonggyo religion as a day to venerate Tan’gun (Baker, pp. 90-91).

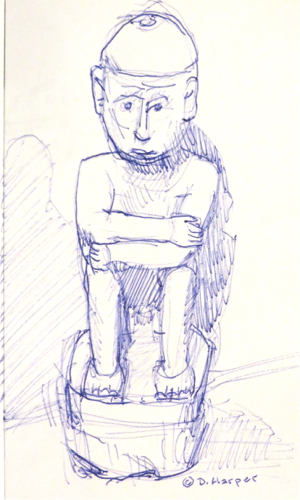

The image above is a public domain image of Tan’gun from Wikimedia Commons (I edited this image for legibility). Unfortunately, Wikimedia Commons does not tell us what painting this image comes from. If you search for additional images of Tan’gun on the Web, note that his name is sometimes transliterated as Dangun.