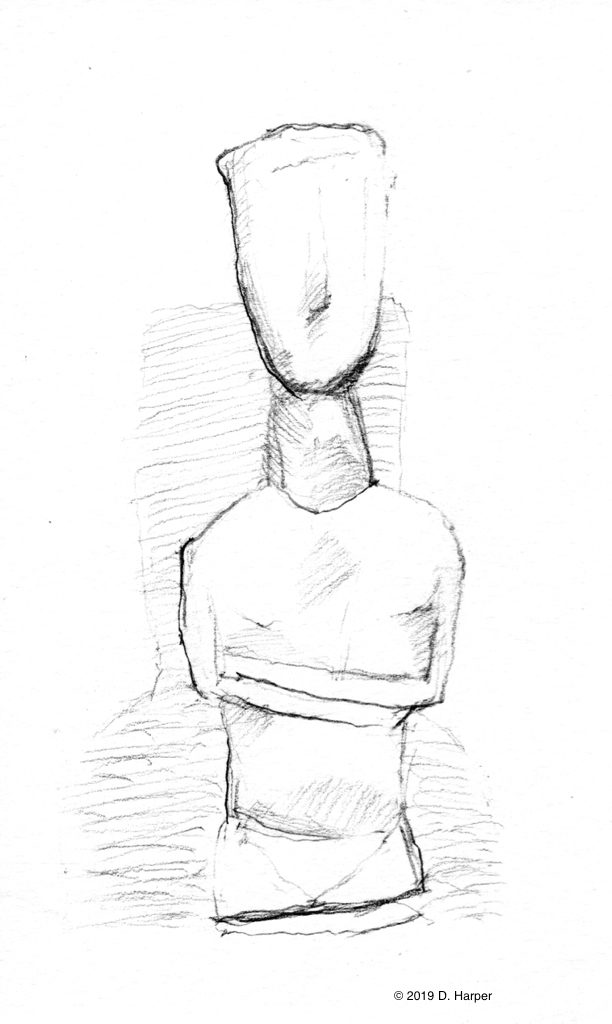

Our Coming of Age class took a field trip to the Asian Art Museum to see images of divinities. There we saw a beautiful jade sculpture of Ch’ang-O (Pinyin: Chang-e), the Moon Goddess. It’s just a few inches tall, but highly detailed: Ch’ang-O is smiling beatifically, and she is accompanied by her rabbits, one of whom is grinding something in a mortar and pestle:

Ch’ang-O is still honored in Chinese popular culture, at the Mid-Autumn Festival which takes place on the fifteenth day of the eighth Lunar month. More than one version of Ch’ang-O’s story is told, but the general outlines of the various versions are similar:

Ch’ang-O is an immortal being; she and Houyi are sweethearts. One day, ten suns appear in the sky, the sons of the Jade Emperor of Heaven, and these ten sons cause much damage; Houyi takes up his bow and arrow and shoots down nine of the ten in order to save the earth. Ch’ang-O loses her immortality by offending the Jade Emperor in some way. Houyi obtains a concoction that will make one person immortal (in some versions the pill could be split between Houyi and Ch’ang-O, making them both very long-lived, but not immortal), and this concoction is formed into a pill. Ch’ang-O takes the entire pill herself, either mistakenly or on purpose, upon which she not only becomes immortal, but she begins floating upwards towards heaven. At last she lodges permanently on the moon.

The Rabbit in the Moon

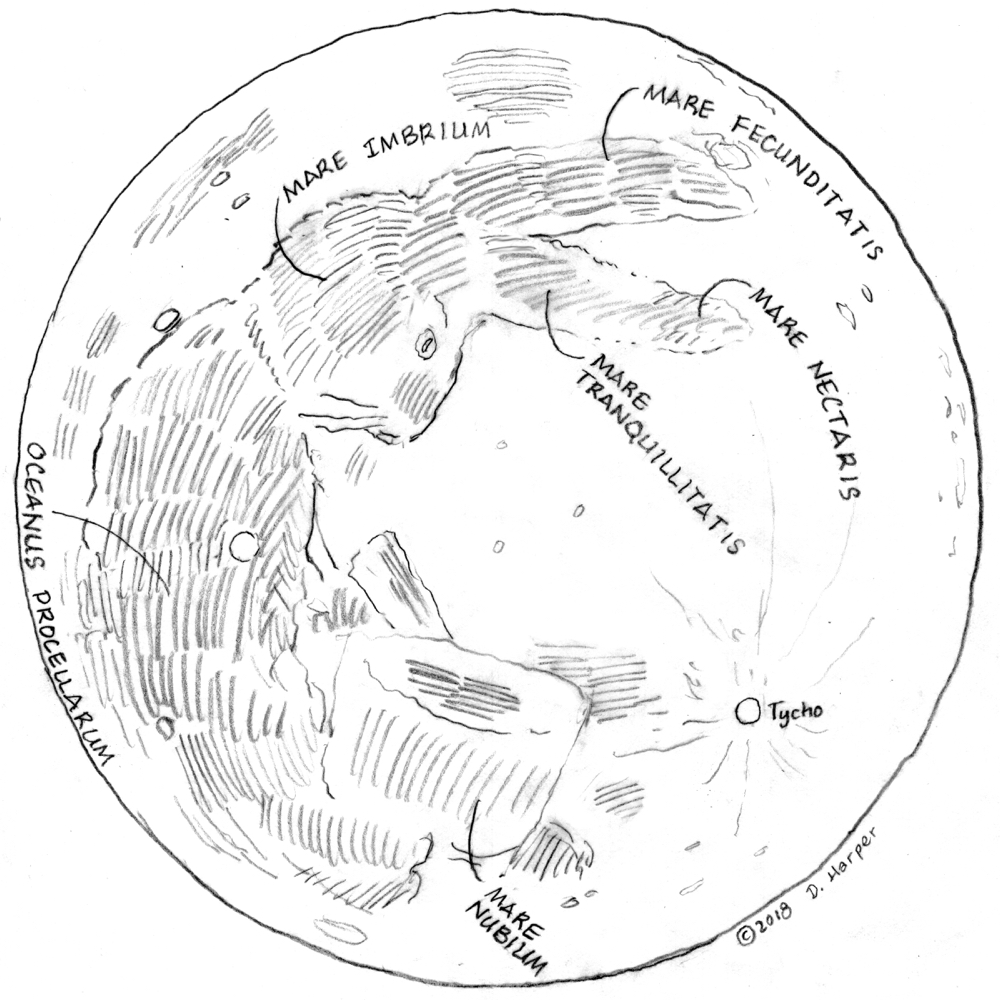

The reason there must be rabbits in the Moon is simple. In the West, we look at the moon and see the Man in the Moon, but in East Asia it is common to look up and see the Rabbit in the Moon; the Rabbit has a mortar and pestle in which it grinds herbal medicine, rice cakes, or mochi (depending on who tells the story). The body of the rabbit corresponds to roughly lunar landscape features as follows: left ear — Mare Fecunditatis; right ear — Mare Nectaris and Mare Tranquilitatis; base of ears — Mare Serenitatis; head — Mare Imbrium; body — Oceanus Procellarum. The mortar which the Rabbit uses for grinding is centered on the Mare Cognitum. For Westerners, here’s a sketch of the Moon Rabbit:

To help you find the Moon Rabbit next time you look at the moon, remember that the crater Tycho is just to the right of the Rabbit’s mortar.

How divine is Ch’ang-O?

Something we ask Coming of Age participants to consider when they look at images of deities is where they would place that deity on the following rough scale:

1. Ordinary human

2. Extraordinary human (prophet, sage)

3. Semi-divine (more than human, not quite a god or goddess)

4. Human who became divine

5. God or goddess with a non-human form

6. God or goddess that acts like a human

7. God or goddess that is far above humans

8. God or goddess so divine that humans cannot know it

In the stories about her, Ch’ang-O started out as — perhaps — semi-divine (more than human, not quite a goddess); then became completely human; then became immortal once more; and finally wound up as the Moon Goddess. Most Westerners, influenced by the strongly Western tradition of ancient Greek philosophy, tend to think of a deity as unchangeable, the “Unmoved Mover”; but far more human cultures have deities that can change in response to events. Thus Ch’and-O serves as a perfect counter-example for Westerners (both theists and atheists) who dogmatically assert that God is perfect and does not change.

Ch’ang-O in popular culture

The story of Ch’ang-O doesn’t leak out much beyond the boundaries of the Chinese American community (or other East Asian communities). But once in a while, the story of Ch’ang-O makes it into Western popular culture. The most notable example of this was just before the first humans set foot on the moon.

Here’s the Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription of the Apollo 11 Lunar mission, from July 20, 1969, not long before the Lunar Module landed on the moon:

03 23 16 18 CC [Capsule Communicator, i.e., Mission Control]:

…The “Black Bugle” just arrived with some morning news briefs if you’re ready.

03 23 16 28 CDR [Commander, i.e., Neil Armstrong]:

Go ahead.

[some material omitted]

03 23 17 28 CC:

Roger. Among the large headlines concerning Apollo this morning, there’s one asking that you watch for a lovely girl with a big rabbit. An ancient legend says a beautiful Chinese girl called Chang-o has been living there for 4000 years. It seems she was banished to the Moon because she stole the pill of immortality from her husband. You might also look for her companion, a large Chinese rabbit, who is easy to spot since he is always standing on his hind feet in the shade of a cinnamon tree. The name of the rabbit is not reported.

03 23 18 15 LMP [Lunar Module Pilot, i.e., Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr.; this was latter corrected to Michael Collins]:

Okay. We’ll keep a close eye out for the bunny girl.

(National Aeronautics and Space Administration, “Apollo 11 Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription,” Tape 61/3 page 270 [Houston, Texas: Manned Spacecraft Center, July, 1969], pp. 178-179.)

— And don’t let the conspiracy theorists fool you: the Apollo astronauts saw no sign of Ch’ang-O, nor of any rabbits, nor of a cinnamon tree (actually a cassia tree in the myth).

Updated 3/7/18 with revised drawing and Apollo 11 transcript.