Busy sidewalk in Oakland. Woman talking on cell phone.

“Ballet is good for girls.”

Pause.

“It makes them polite.”

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

Busy sidewalk in Oakland. Woman talking on cell phone.

“Ballet is good for girls.”

Pause.

“It makes them polite.”

One of the wonderful people who teaches comprehensive sexuality education in our church sent along a link to a post on Imgur headed: “Two years ago today, my then 14 year old sister got suspended for submitting these answers for her sex-ed class. I’m so proud of her.” Then there’s a photo of a worksheet titled “Objections to Condoms.” Kids were supposed to come up with possible responses to various excuses for not using condoms.

So, for example, one of the excuses for not using a condom was: “Condoms are gross; they’re messy; I hate them.” To which this creative girl replied: “So are babies.”

Mind you, a couple of the replies are just plain unconvincing, e.g. — Excuse: “I’d be embarrassed to use one”; reply: “Look at all the fucks I give.” Yeah, whatever.

But some of the replies, while very snarky, just might actually work in the real world, e.g. — excuse: “I don’t have a condom with me”; reply: “I don’t have my vagina with me.” This is not a good response to put on a worksheet that a public school teacher has to read; but a snarky early adolescent girl who needs to use a little humor to get through to a boy might find that reply useful.

This brings up an interesting point of educational philosophy. A core element of my educational philosophy is to start where the learner is. Some early adolescents learning about sex and sexuality may be most comfortable using snark and f-bombs to talk about sex. Of course we want to move them to a more reasoned form of discourse, a way of speaking that will allow them to talk about sex with potential partners openly, humanely, and with emotional intelligence. But we may have to listen to their f-bombs for a while before we get them there.

During the Supreme Court argument session on Obergefell v. Hodges, according to the transcription, Justice Alito had the following exchange with Mary Bonauto, Esq., representing the petitioners:

JUSTICE ALITO: But there have been cultures that did not frown on homosexuality. That is not a universal opinion throughout history and across all cultures. Ancient Greece is an example. It was – it was well accepted within certain bounds. But did they have same-sex marriage in ancient Greece?

MS. BONAUTO: Yeah. They don’t – I don’t believe they had anything comparable to what we have, Your Honor. You know, and we’re talking about —

JUSTICE ALITO: Well, they had marriage, didn’t they?

MS. BONAUTO: Yeah, they had – yes. They had some sort of marriage.

[p. 14 of the official transcript]

I have some interest in ancient Greek thought, and so I’d like to stop right there for a moment. What sort of concept of marriage did the ancient Greeks have, and is it something we would look to as analogous to our present-day concept of marriage? Continue reading “Ancient Greek marriage laws and same-sex marriage”

I lose consciousness of ugly bestial raid

and repetitive affront as when they tell me

18 cops in order to subdue one man

18 strangled him to death in the ensuing scuffle (don’t

you idolize the diction of the powerful: subdue and

scuffle my oh my) and that the murder

that the killing of Arthur Miller on a Brooklyn

street was just a “justifiable accident” again

(again)

That’s from June Jordan’s “Poem about Police Violence,” from way back in 1980. The poets have been telling about this for at least thirty five years, longer than a lot of you have been alive. And if we forgot (because who reads poetry any more), there was Oscar Grant. And Eric Garner. And now Freddie Gray.

June Jordan said:

People have been having accidents all over the globe

so long like that I reckon that the only

suitable insurance is a gun

I’m saying war is not to understand or rerun

war is to be fought and won

Didn’t Malcolm X say that back around 1960? And — OK, I hear you, violence is not the answer, and I agree with you on that one. But then what is the answer? Because we seem to be hearing the same old news again.

The following is excerpted from “Symbolic Storytelling, Freedom Movements, and Church Education: Cesar Chavez as a Virtuoso of Identity,” Ted Newell, Religious Education, vol. 109, no. 5, p. 550:

“Worldviews draw on assumptions, on storied answers to the most basic questions of humankind. Their presuppositions are not irrational but pre-rational. A worldview framework is required for thought itself. Worldviews are the lenses through which humans see the cosmos and themselves within it. Accordingly, an attempt to adjudicate between worldviews by means of reason is likely to be a disguised attempt of one worldview to subdue another. Reason is not neutral but is particular, drawn from its own presuppositions — scientific reason included (Kuhn 1996; Harding 1986; Milbank 2006). There is no neutral ground on which to stand.”

There’s nothing here that is new or surprising, given the ongoing conversations about multiculturalism and postmodernism. But what does interest me is where Newell takes this argument: he calls for us to re-tell old stories for new times: “The older meaning-making matrices have broken down. New expressions of old stories or perhaps new stories are needed.” Newell is speaking from within a Christian worldview, and so he calls for new “holistic story-weavers” to re-tell the story of Christianity in order to bring renewal.

It would be interesting to try to re-tell the story of Unitarian Universalism in order to bring renewal. But what is our story? Is ours a story of a new reformation of Christianity that has called us into a post-Christian worldview? (This is a story Dana Greeley hints at in his 1971 memoir Twenty Five Beacon Street.) Is ours a story of human beings struggling to manifest in our religious communities a worldview of justice for all persons? (This is a story that Mark Morrison-Reed sometimes tells in his books.) Or maybe this — we don’t have one central compelling story that we can all unite around, in the way Ted Newell says that “Christianity must always be called back to [the story of] the Cross” — is ours a story of not having one story? (And this may be the story we most often tell about ourselves — “You can believe anything you want” — but I don’t think it is a very interesting or compelling story.)

Actually, instead of asking about our stories, it might be more interesting to ask about who are storytellers are: Which Unitarian Universalists are currently telling compelling new stories, stories which may bring renewal? The best example of a Unitarian Universalist “holistic story-weaver” that I can think of is Mark Morison-Reed. Aside from Mark’s stories, the Unitarian Universalist stories I’ve been hearing are either too particular to be holistic, or they rely on reason to subdue and subjugate competing worldviews.

The story that I’m waiting to hear will begin with the story of the relationships between humans, and how humans can manifest justice in their relationships with one another. But it will also tell about the relationship of humans to transcendence. It will also tell about the relationship of humans to non-human beings.

And it will be a really good story, one that won’t put me to sleep — which means it will be a story that’s good enough, and deep enough, so it can be told to children without having them slump down in their seats from boredom.

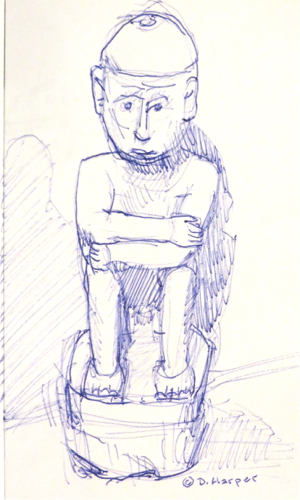

Above: Sketch of a “ceremonial deity,” Philippines, c. 1930. Wood and shell. Asian Museum of Art.

One of delights of going to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco is seeing the diversity of depictions of deities. Today I particularly noticed the unnamed deities — like this sculpture of an unnamed ceremonial deity, made in the Philippines around 1930. Why do we not know the name of this deity? Is it because it is a minor deity, and thus not widely identifiable (though perhaps readily identifiable by a devotee)? Did it never have a name that could be spoken by humans? Or was this a deity like the Roman Lares familiares, the household gods, who don’t seem to have had names, or whose power was so geographically restricted that their names perhaps were known only to the household they protected?

I think that the end of Christendom is allowing us to see such minor deities more clearly. In the worldview of Christendom, only the major deities — the wildly transcendent deities, Jehovah’s direct competition — were worthy of serious attention. Now maybe we can pay a little more attention to the many minor deities who inhabit the metaphorical space between those distant transcendent deities and mortal creatures.

Alfred Salem Niles (1894-1974), professor of aeronautic engineering at Stanford [note 1], helped start the present church — then Unitarian, now Unitarian Universalist — after the Second World War. In 1958, he wrote this detailed memoir of how our present church began. Since he was one of the few people to attend both Unitarian churches in Palo Alto, his memoir helps connect those of us in the present-day church with the early Palo Alto Unitarians.

I am publishing only the 500 words of this 11,000 word essay here. The complete essay will soon be available in print form at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto.

The Spring of 1947

In 1927 when the writer came to Palo Alto, the old Unitarian Church at Cowper St. and Charming Avenue was still functioning, but rather feebly. The minister was a woman who later gained considerable notoriety as a fellow-traveler, though her proclivities along that line were not yet apparent [note 2]. There was no Sunday School that I know of, and attendance at the morning services was small. In earlier years the church had been much more active, but the minister at the time of World War I had been a pacifist and conscientious objector, and this had caused a split in the church from which it never recovered. Another thing which I think was an important obstacle to recovery was the quality of the pews in the old building. They were the most uncomfortable ones that I have ever encountered. Since mortification of the flesh does not appeal to Unitarians as a technique of salvation, those seats must have discouraged many possible members. Morning attendance got so small that we tried having services in the evening. But that did not help. Our woman minister resigned, and for a while we had a student from the Starr King School preach to us. Finally, about 1929, services were discontinued, and after a few years the church organization was dissolved, the church building returned to the American Unitarian Association, (3) which sold it to a Fundamentalist group for about $230 less than the mortgage, and there was no more organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for several years.

During the 1930s the Chaplain at Stanford was Dr. D. Elton Trueblood, a Friend [i.e., a Quaker] with quite liberal views and an excellent speaker. Many Unitarians got into the habit of attending services at the Stanford Church as a result. But he resigned and was succeeded by more orthodox men, and most of the Unitarians in town lost the church-going habit. One result of this was that quite a few of us, although well acquainted with each other, did not realize that we were fellow-Unitarians. The writer can testify to his own surprise, in 1947, to find that the head and one of the professors of his department at Stanford were also Unitarians. We just had never discussed religion with each other.

In the autumn of 1946, Rev. Delos 0’Brian came to San Francisco to be the American Unitarian Association (A.U.A.) Regional Director for the West Coast, with the objective of reviving some of the dormant Unitarian churches and organizing new ones in favorable locations. I was then a member of the Church of the Larger Fellowship, and noticed an item about Mr. O’Brian’s activity in the Christian Register for November 1946. It was not until some time in February 1947, however, that I went to see him at his office at the corner of Sutter and Stockton Sts. It was about noon when I got there, so we went across the street to the Piccadilly Inn to have lunch and talk about the possibility of starting something in Palo Alto. He had the names of about a dozen members of the Church of the Larger Fellowship in Palo Alto, and a similar number in San Mateo, but had not yet made many contacts with those in either group, and was undecided as to which one to start and I think it was my visit which caused him to decide to start with Palo Alto, and that the revival of the Palo Alto Church started at that meeting….

Continue reading “A new Unitarian church in Palo Alto, 1947”

A continuation of a documentary history of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

After the departure of Rev. Bradley Gilman, the congregation managed to get back on its feet, first with no minister, then with the experienced leadership of Rev. Elmo Arnold Robinson, a Universalist minister. But the financial situation worsened through the late 1920s, the congregation began to decline, and the Great Depression made it impossible to continue.

An Experiment in Palo Alto (1920)

[In the previous post, the excerpt from Josephine Duveneck’s autobiography told how the relationship between Rev. Bradley Gilman and the congregation grew strained. It is worth noting that Palo Alto was the last congregation that Gilman served. This chapter begins with an explanation of how the Palo Alto church experimented at having an entirely lay-led congregation. Edith Mirrielees asserts that the reasons for not hiring a minister were not financial, leaving us to conclude that Bradley Gilman soured the congregation on ministers.]

The Unitarian church in Palo Alto was established in 1905. From its establishment until the autumn of 1919, the church followed the way of most Unitarian churches, retaining a resident minister and supporting him with an enthusiasm that waxed or waned according to the circumstances surrounding the individual pastorate.

In May, 1919, the Rev. Bradley Gilman, at that time the incumbent, left Palo Alto for a visit to the Eastern coast. Some months later he sent in his resignation. When the congregation came together to consider the resignation, many of its members felt unwilling to begin the search for a new minister until an experiment had been made in conducting the church in another manner. For some years there had been a growing conviction among members of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that the presence of a professional minister was not necessarily essential to the continuance of their church or to its welfare, and after thorough discussion in congregational meeting it was determined to do without one, the pulpit to be tilled by members of the congregation and community or by visiting Unitarians. the other duties of the pastorate to be assumed by the congregation. It is worth noting that this decision was not reached because of money difficulties. The church at this time, though by no means wealthy, was in sound financial condition, without debt and with as many contributors as it had had during the previous year when a minister had been in residence. It should be noted, too, that the essential Unitarianism of the church is in no way affected by the change; the congregation is a congregation of Unitarians, but one wherein congregational government and responsibility is now carried a step farther than it has been before.

The attempt was at first frankly experimental. After four months of trial, it seems so far to have justified itself that there is at present no probability of a return to earlier conditions. Throughout the winter months, the pulpit has been regularly filled, often by speakers with a notable message, membership in the church and attendance at services have both materially increased, money has come in in quantity sufficient to meet all obligations and to make possible the establishment for next year of a scholarship at Stanford University, which it is the hope of the congregation to continue from year to year.

Rut these things, though they are encouraging, are only the outside results of the experiment. More important than any one of them is the effect of the change upon the relation of members of the congregation to the church and to each other. A new unity of purpose, an increased sense of fellowship, has been the most promising growth of the last few months. The presentation from the pulpit of many points of view 1ms promoted that tolerance essentially dear to Unitarians. The necessary sharing of responsibility has, as it is likely to do, increased the willingness to take responsibility. It goes without saying that the work has not been equally shared; as is the case in practically every congregation, one or two members have carried the heaviest part of the burden, but in very considerable number — a number much larger than was normally found under the old condition — have taken some part, with a resultant growth in actual neighborliness and interdependence.

It is by no means the thought of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that other bodies of Unitarians would necessarily be wise to follow in their footsteps. For any congregation, the wisdom or unwisdom [sic] of such an attempt depends upon the nature of the community in which the church is situated. It has to be a community which provides a fair number of thoughtful speakers; it has to be a congregation blessed with at least one member ready steadfastly to put the church’s welfare before his own, and neither of these things is easy to find. For Palo Alto, however, the experiment thus far has been promising enough to justify its further trial.

— Edith R. Mirrielees, The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 29, no. 5, May, 1920, p. 125.

[Note: Mirrielees was professor of creative writing at Stanford, and a teacher of John Steinbeck (Jeffrey Schulz and Luchen Li, Critical Companion to John Steinbeck [Facts of File: 2005), p. 301.]

A continuation of a documentary history of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

The years of the First World War proved difficult for the Palo Alto Unitarians. It was a congregation full of pacifists, but after the entry of the United States into the World War, the American Unitarian Association demanded that every congregation that received funding must support the war wholeheartedly. A financial report of the A.U.A. published in the June 6, 1918, issue of The Christian Register (p. 19) shows that the A.U.A. was paying their minister of the time, Bradley Gilman, $50 a month, or $600 a year.

The Palo Alto Unitarians had been accustomed to the pacifist views of former ministers Rev. Sydney Snow and Rev. William Short, but the war years forced them to accept the pro-war ministry of Bradley Gilman. The relationship with Gilman appears to have been strained; he left after only two years, and never served another congregation as minister; and the Palo Alto Unitarians tried to do without a minister for nearly two years.

New Unitarian Pastor (1915)

The church at Palo Alto has called to the vacant pulpit Rev. William Short, Jr., now in Boston, and highly recommended by those who know him, and also know the requirements of the church calling him. Mr. Short has accepted the call and will enter upon his ministry on the third Sunday of November.

— The Pacific Unitarian, vol. 15, no. 1, November, 1915 (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), p. 7.

New Unitarian Pastor.— A reception in honor of the new Unitarian church pastor, Mr. William Short, Jr., who has recently arrived from the east, was held in the Unitarian church hall last evening.

— from “Palo Alto Notes” in The Daily Palo Alto [Stanford], vol. 47, no. 58, November 18, 1915, p. 3.

———

A “Centre of Liberalism” on the Peninsula (1917)

Palo Alto, Cal.— Unitarian Church. Rev. William Short, Jr.: The Palo Alto church has had a very interesting two years with Rev. William Short, Jr., as minister. Although new to the service, Mr. Short has brought to it an earnestness and vigor, and a great broad humanity, which have meant to the church increased growth in those principles upon which it is founded. In this tremendous national crisis, when the democracy of the country is on trial, the Palo Alto church has been one of the very few where the privilege of complete freedom of speech in the pulpit has not been restrained. The membership of the church is small, about forty in number, and the lack of moral support due to isolation from other centres of liberal thought is very keenly felt. The nearest sister church is in San Jose, eighteen miles distant, and the next nearest in San Francisco, over thirty miles in the other direction, the dominating note in the theology of the region being definitely conservative.

The congregation is of a vigorous and thoughtful kind, avoiding a deadly conformity of opinion. It has maintained its stand for the universal character of religion. The pamphlet-rack in the vestibule must be constantly refilled. In conformity with its Unitarian heritage, the church hall has given hospitality during the past winter to Mr. John Spurgo, the noted Socialist speaker; to the American Union Against Militarism, which is earnestly fighting the cause of democracy; and to Mme. Aino Malmberg, a refugee from the persecutions of Old Russia and an ardent advocate of the cause of oppressed nations. Two physical training clubs for women and girls have had their home in the hall, as well as a dub to encourage the finer type of social dancing. The church passed a resolution of approval of the visit of Mr. Short to Sacramento in March in the interests of the Physical Training bills. The Women’s Alliance at its annual meeting was fortunate in having as guests Dr. Franklin C. Southworth and Mrs. Southworth and Secretary Charles A. Murdock. It has been the privilege of the church to welcome to the pulpit Rev. Charles F. Dole of Jamaica Plain, Mass. His sermon was “The Religion Beneath All Religions.” The church, probably in common with most others, has suffered somewhat from the mental and financial depression due to war conditions, though the members realize the importance of maintaining its integrity as the only centre of liberalism in a wide extent of country.

— The Christian Register (Boston: American Unitarian Association), vol. 96, no. 29, July 19, 1917, p. 694.

———

Denial of Writ of Habeus Corpus for William Short (1918)

[The following is excerpted from the hearing for a writ of habeus corpus filed by Rev. William Short’s wife, following his arrest and detention on charges of draft evasion. The Peoples’ Council mentioned in the writ was a national pacifist organization headed by Scott Nearing.]

Ex parte SHORT.

(District Court, N. D. California, First Division. September 5, 1918.)

No. 16417.

In the matter of the application of the wife of William Short for a writ of habeas corpus to secure his discharge from the custody of military authorities. Writ denied, and Short remanded to the custody of military authorities. …

DOOLING, District Judge. The wife of William Short seeks his discharge on habeas corpus from the custody of the military authorities. The record shows that Short, who will be designated herein as the registrant, on January 14, 1918, returned to his local exemption board his questionnaire, in and by which he claimed exemption as “a regular or ordained minister of religion.” In support of such claim he stated:

That “he had been admitted to Unitarian ministerial fellowship In January, 1916, at Palo Alto, Cal., and that on June 5, 1917, he was minister of Palo Alto Unitarian Church.”

To the question, “State place and nature of your religious labors now,” he returned no answer; but in response to the question, “Give all occupations at which you have worked during the last 10 years, including your occupation on May 18, 1917, and since that date, and the length of time you have served in each occupation,” he answered:

“Unitarian minister 1 year and 10 months. From May 15 to June 25, Unitarian minister, time included above. Chairman Northern California branch Peoples’ Council (temporarily) 5 months. Student for balance of time during 10 years.”

Upon these answers he was placed in class VB; that is to say, in the class of a regular or duly ordained minister of religion.

On June 6, 1918, a letter was sent to the local exemption board by the United States attorney, stating that registrant — “registered for the draft at Palo Alto on June 5, 1917. At that time he was acting as a minister in the Unitarian Church of that town, but shortly thereafter resigned from the church and has not been connected in any way with any church since, but has, on the contrary, devoted his time to the activities of the Peoples’ Council, which organization is decidedly unpatriotic in my opinion. I believe that Short should be reclassified and compelled to do military service, other things being equal.” …

From this reclassification he appealed to the district board, which on June 15th denied the appeal.

Thereafter, and on July 19, 1918, he was arrested and on July 20, was by the local board for division No. 1 in San Francisco, certified as a deserter, and delivered to the commanding officer of the United States army, and now is in the custody and under the control of such officer. …

Registrant has suffered no injury at the hands of the local board, and the writ of habeas corpus is therefore discharged, and he is remanded to the custody of the military authorities.

— The Federal Reporter: Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit Courts of Appeals and District Courts of the United States (St. Paul: West Publishing Co.), Dec. 1918-Jan. 1919, vol. 253, p. 839.

Rev. Clarence Reed served longer than any of the other ministers of the old Palo Alto Unitarian Church, for six years from 1909-1915. Arguably, these were the best years for the congregation: they built the social hall that had been originally planned; the Sunday school grew to perhaps 60 children and teenagers; the Women’s Alliance had perhaps 40 members; and perhaps 200 adults were affiliated with the congregation. Here are documents that tell the story of the congregation during these years:

Rev. Florence Buck in Palo Alto (1910)

[Rev. Florence Buck was one of the better known women who served as Unitarian ministers in the early part of the twentieth century. During her brief stay at Palo Alto, she inspired at least one teenaged girl to become a minister — more on that teenager in a subsequent post on the Palo Alto Unitarians.]

Rev. Florence Buck has been given a year’s leave of absence at Kenosha, Wis., and is supplying the pulpit at Palo Alto, Cal.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), October, 1910, p. 5.

Mr. Reed, the minister of the Palo Alto Society, has been ill, but hopes to take up work again in December. His pulpit mean-time is being supplied by Rev. Florence Buck.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), November, 1910, p. 8.

WOMAN MINISTER TO FILL PULPIT

Rev. Florence Buck Has Been Chosen Pastor of Unitarian Church of Alameda

Alameda, [Calif.,] Dec. 19. — Rev. Florence Buck has accepted a call to become the minister of the First Unitarian church of this city. She will begin her pastorate Sunday, January 1, on which date she will conduct services and deliver her initial sermon. She will be the first divine of her sex to take permanent charge of a local church and will be one of the few women ministers in service on the Pacific coast.

The new minister is unmarried. She has had extensive experience In religious work and has been a preacher of the Unitarian faith for some years. She was associated with Rev. Marian Murdock in conducting a church in Cleveland, O. She also filled the pulpit of a Unitarian church in Kenosha, Wis. Of late Rev. Miss Buck has been temporarily occupying the pulpit of the Unitarian church in Palo Alto in the absence of the regular minister, Rev. Clarence Reed, former pastor of Alameda Unitarian church, who is on a vacation in Japan. Since Rev. Mr. Reed left here and went to the Palo Alto church the First Unitarian church has been without a regular pastor. Rev. J. A. Cruzan, field secretary for, the Unitarian society or America, has been acting temporarily. Rev. Miss Buck was heard here twice in the pulpit: of the Unitarian church last month. On both occasions she made a good impression and the trustees decided to extend her a call.

— San Francisco Call, vol. 109, no. 20, December 20, 1910, p. 11.

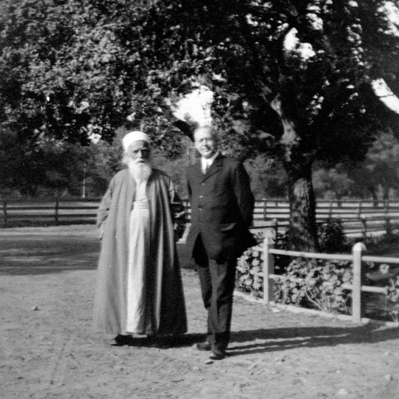

Above: Rev. Clarence Reed and the Baha’í prophet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palo Alto, 1912