Yet another late start. After driving for just two and a half hours, it was time for lunch. I stopped in Colfax, Iowa, and went in to Poppy’s Restaurant. It was lunch hour, and there were half a dozen parties of men, working stiffs, some wearing blaze yellow shirts, some wearing ball caps. Some of the guys talked back and forth from one table to the next. At the table next to mine, two younger men talked seriously about whatever job they were on, then one of them made a call on his cell phone and spoke in the jargon of a trade I wasn’t familiar with.

I drove south from Colfax to Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, a restored prairie with some oak savanna. Seven hundred acres of the refuge are fenced off and a small bison herd lives there, while scientists study the impact these large mammals had on the prairie ecosystem.

At the visitor center, I spent half an hour talking with a man, probably half my age, who worked for the Department of the Interior. We talked about long distance hiking trails, and I learned from him that the National Park Service now administers the North Country Trail, stretching some 4,600 miles from North Dakota through New York to the Vermont border. He also waxed enthusiastic about the Florida Trail, administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which currently extends for 1,000 miles through Florida. I told him he should take a sabbatical from his job and hike one of those trails, and he said he takes winters off and last winter he went to Nepal.

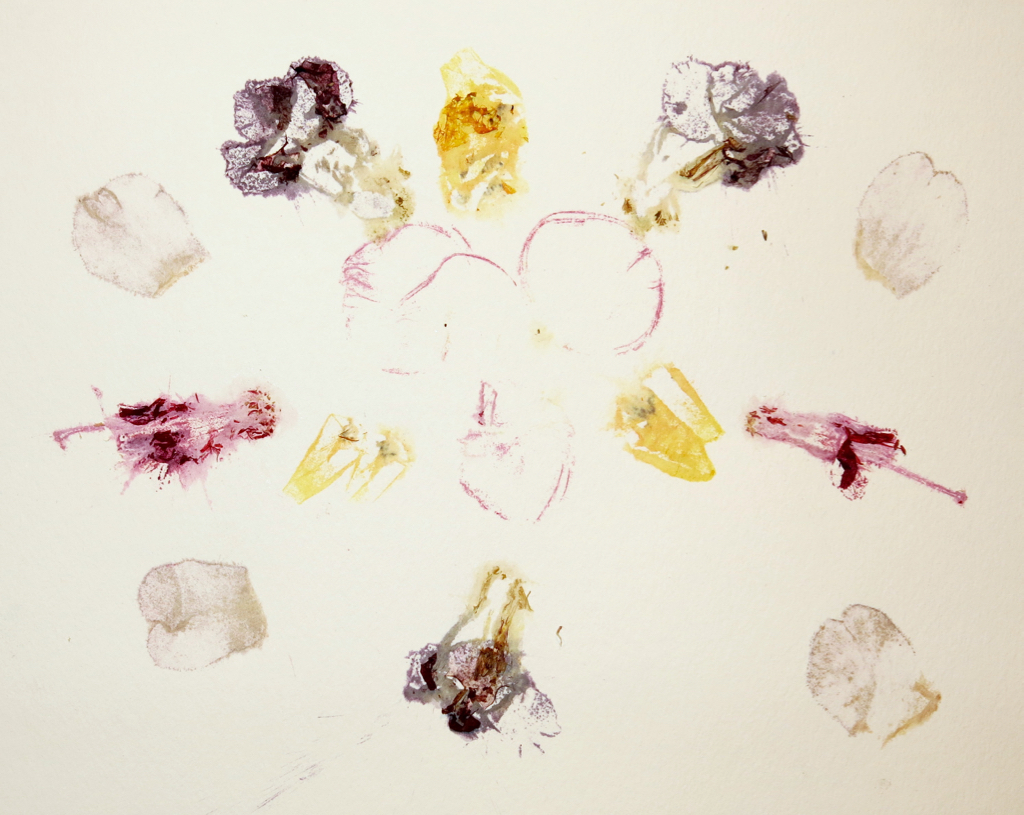

I could have spent more time listening to him talk, but I wanted to get outside. I went out into the hot humid summer day and walked two nature trails, one through oak savanna and one that started high on a prairie hillside then dropped down into a riparian corridor with small willows and a mostly dry stream. Dickcissels were everywhere, Indigo Buntings flew through the lower branches of the oaks, Field Sparrows sang in the grass, and I watched an Orchard Oriole feed its young. A checkerspot butterfly basked in the shade, on the front of a concrete bench.

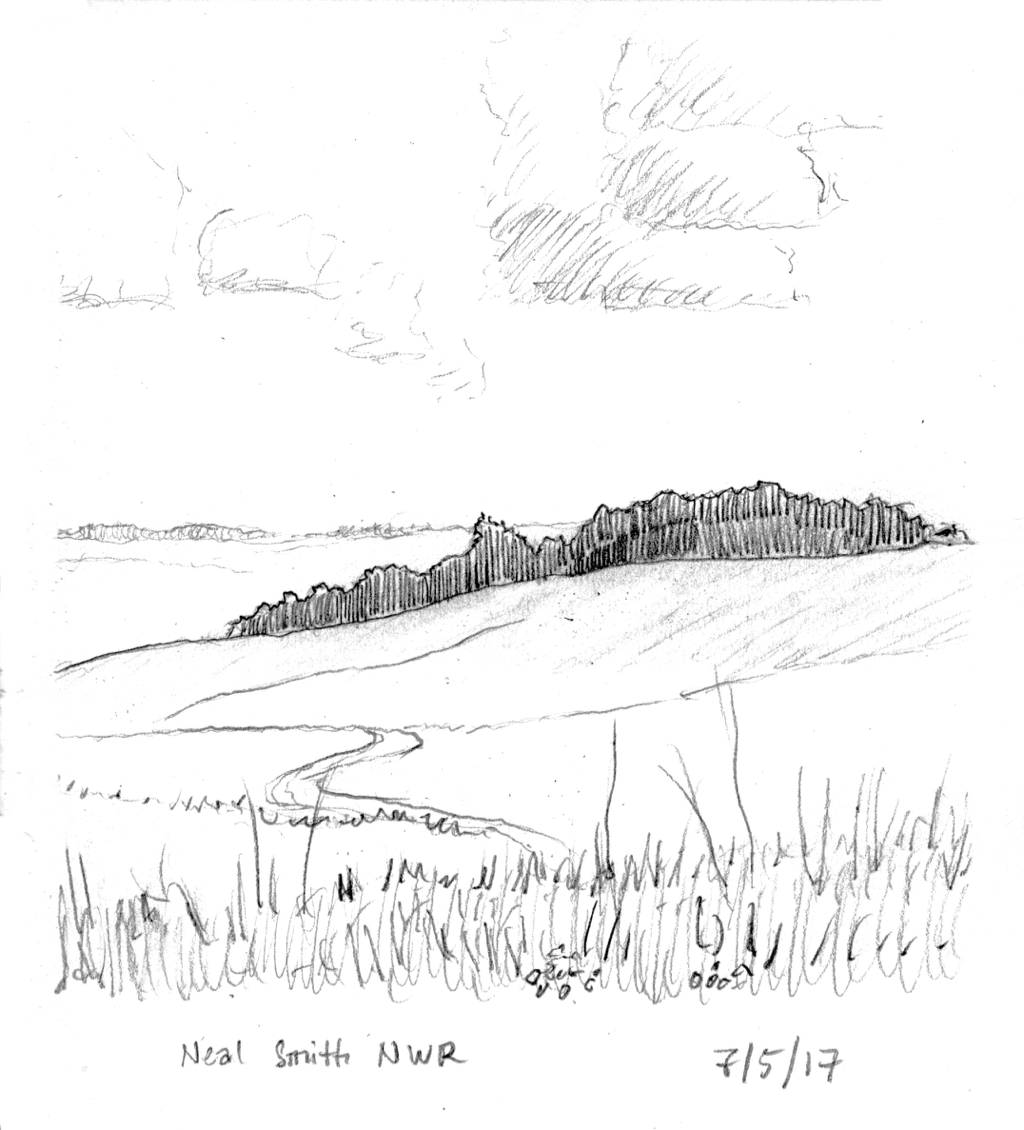

Before I got back into my car, I stopped to look at the landscape of the restored prairie and oak savanna. The contours of the land were what you’d expect of central Iowa, rolling hills and valleys with small streams. But without the usual dark green covering of soybeans or corn, the landscape took on a different aspect: it was lighter in color, and the air was filled with bird song. I tried to imagine Iowa without any farms, with great herds of bison grazing on the prairie, but it was hard to do so; this is a landscape that we humans have altered almost beyond recognition in the past century and a half.

And tonight I’m staying in Joliet, in the growing sprawl of Chicagoland, where malls and housing developments have replaced corn and soybeans. It’s even harder to imagine this landscape as it must have been before Europeans settled here.