There are two basic ways to track down faith communities in your area. One way is to find all the faith communities in a relatively small geographic area; that’s the approach I took in an earlier post. The other way is to try to find representatives of as many different kinds of faith communities within, say, and hour’s drive of your location. In this approach, you only need to find one representative of each kind of faith community; so, for example, once you find one Roman Catholic church, you ignore the rest and move on to another kind of faith community.

To carry out this second kind of search, you need some kind of general listing of different types of faith communities. But generating such a list proves to be a challenge.

The biggest challenge is identifying types of Christian churches; Christianity is a wildly diverse religion, with hundreds of self-identified denominations. Believe me, you don’t want to be chasing down every single Baptist denomination. Instead, what’s needed is a higher-level taxonomy. Fortunately, the World Council of Churches provides a useful taxonomy, which we can accept as reasonably authoritative since it was developed by Christians to describe themselves. Obviously, those groups that do not belong to the World Council of Churches might not approve of it; but it provides a useful and reasonably good taxonomy. And we can take a similar approach for other religious groups: look at how Jews organize themselves, for example, for a basic taxonomy of Judaism.

But then how do we choose still broader categories? What are the top-level divisions of religions? To answer this question, I mostly followed the broad divisions of religions used by Harvard’s Pluralism Project. This project, started by scholar Diana Eck, has been investigating religious diversity in the United States since the 1990s; and in the course of their work, they have developed a practical division of world religions.

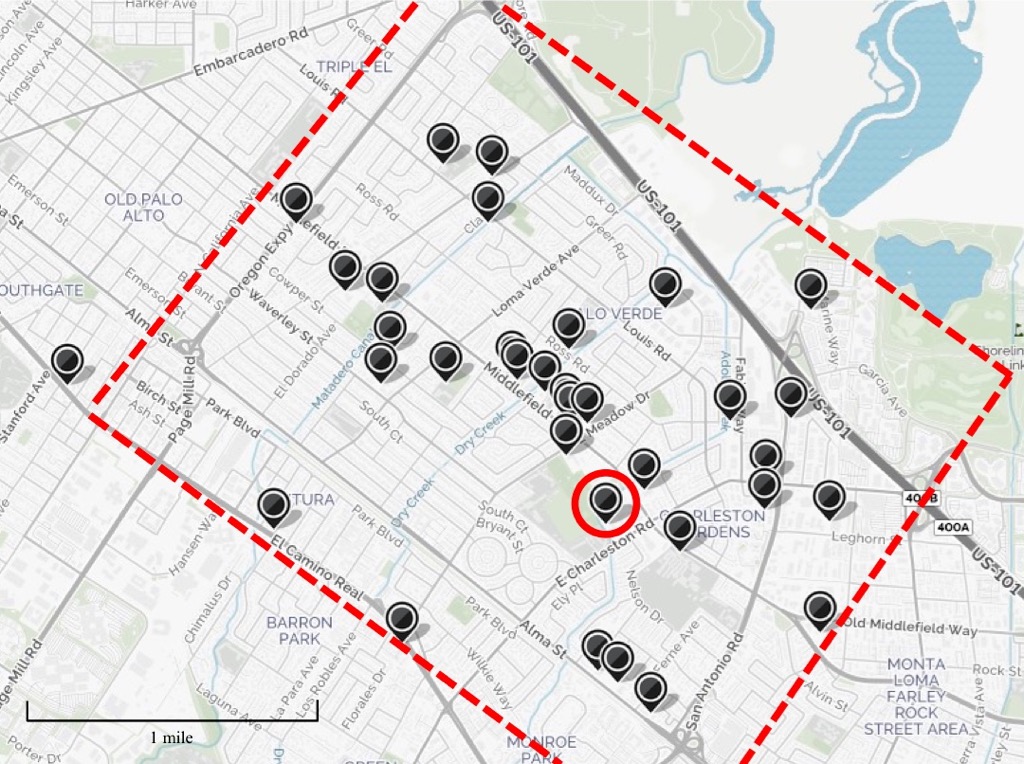

Combining these various taxonomies, I developed a general list of types of faith communities. Based on that list, I tried to track down one or two local faith communities for each major division within the taxonomy within an hour’s drive of our faith community, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto. The list proved to be a great help in tracking down more obscure faith communities: because I knew what I was looking for, I could do more effective Web searches.

Even if you don’t live near Palo Alto, you may find my list of faith communities useful for tracking down different types of faith communities in your area. You’ll probably have to revise this list for your area; but it should prove to be a useful starting point. It took many hours to research this list; and I hope I save you some of those hours of research, so you can put your time into refining the list, and finding faith communities.

The main thing I took away from this exercise: the United States has an absolutely amazing diversity of religious groups.

Now, here’s the list (updated and corrected 11/2; 11/3; 11/4; more additions and corrections 11/8):

LIST OF FAITH COMMUNITIES IN AND NEAR PALO ALTO

A: Baha’i faith communities

B: Buddhist faith communities

C: Christian faith communities

CC: Post Christian communities

including Unitarian Universalism

D: Confucian communities

E: Daoist faith communities (Taoist)

F: Hindu faith communities

G: Islamic faith communities

H: Jain faith communities

I: Jewish faith communities

J: Native religions and cultural traditions

K: New Religious Movements

including Humanism and Neo-Paganism

L: Orisa devotion

M: Other traditions

N: Zoroastrian

O: Sikh

General categories for world religions modified from that of the Pluralism Project (here, and here).

A: Baha’i faith communities

Founded in the nineteenth century as a reform of Islam. As of 2016, there are nine continental “Houses of Worship,” serving broad areas. Many local faith communities meet in members’ homes.

Baha’i of Palo Alto

Meets in members’ homes.

Web site

B. Buddhist faith communities

Buddhism may be divided up into schools; the schools often stay within linguistic boundaries, or within the boundaries of one of the historic East Asian nations.

B-1: Theravada

Therevada Buddhism uses as its core texts books in the ancient Pali language. Therevada Buddhism is strongest in Southeast Asia, particularly Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, etc. In the U.S., many Therevada Buddhist groups consist of immigrants from these areas. The Therevada Buddhist faith communities are separated here by dominant linguistic/ethnic group.

B-1.a: Cambodian Therevada Buddhism:

B-1.b: Laotian Therevada Buddhism: Wat Lao Buddhaxinaram

14671 Story Rd., San Jose

No Web site, phone: 408-926-8000. Yelp page

B-1.c: Myanmar/Burmese Therevada Buddhism: Kusalakari Monastery

40174 Spady Street, Fremont

Web site Facebook page

B-1.d: Sri Lankan Therevada Buddhism: Buddhivara

402 Knowles Ave., Santa Clara

Resident monks. Web site

B-1.e: Thai Therevada Buddhism: Wat Buddhanusorn

36054 Niles Blvd., Fremont

Web site

B-1.f: Western culture Therevada Buddhism: Vipassana movement: Insight Meditation Center of the Mid-Peninsula

108 Birch Street, Redwood City

Web site

This center intends to separate Buddhist meditation from Asian cultural forms.

B-1.g: Therevada Buddhism originating in other countries

B-2: Mahayana

The largest division of Buddhism, which includes a number of smaller subgroups. Mahayana Buddhists generally accept a larger number of sacred texts than do Therevada Buddhists. Mahayana Buddhism was historically strongest in China and Chinese-speaking countries, as well as Japan, Korea, etc. The various Mahayana schools of Buddhism spread across linguistic and national boundaries to some extent, especially in the United States; however, even in the U.S. Buddhist schools typically trace their lineages back to a language or country, and they are so divided here.

B-2.a: Chinese Mahayana Buddhism

Tien Hau Temple

125 Waverly Place, San Francisco

No Web site, phone: 415-986-2520.

The oldest Buddhist temple in the U.S.; dedicated to the goddess Tien Hau (according to this NY Times article, 10 October 2008).

Amitabha Pureland: Amitabha Buddhist Society of U.S.A.

650 S. Bernardo Avenue, Sunnyvale

Web site

In Pure Land Buddhism, entering the “Pure Land” is equivalent to attaining enlightenment.

Chan Buddhism: The older tradition from which Japanese Zen Buddhism came.

Heart Chan Meditation Center

4423 Fortran Court #130, San Jose

Web site

B-2.b: Indian Mahayana Buddhism

Triratna Buddhist Community: Founded by Dennis Lingwood, who was a Buddhist monk in India fro 25 years and took the name Sangharakshita, the Triratna Buddhist Community is now a world-wide movement.

San Francisco Buddhist Center

37 Bartlett St., San Francisco

Web site

B-2.c: Japanese Mahayana Buddhism

Buddhist Church of America: Palo Alto Buddhist Temple

2751 Louis Rd, Palo Alto

Web site

The Buddhist Church of America was founded over 100 years ago by Japanese immigrants to the U.S. Theologically fairly liberal.

Nichiren Buddhism: San Jose Myokakuji Betsuin

3570 Mona Way, San Jose

Listing on denominational Web site | Phone: 408-246-0111

Soto Zen: Kannon Do Zen Meditation Center

1972 Rock St., Mt. View

Web site

Zen Buddhism (Chan Buddhism in Chinese) emphasizes direct practice through a form of meditation called zazen. It is the most familiar form of Buddhism to most Americans, to the point that many Americans assume that all Buddhists are like Zen Buddhists.

B-2.d: Korean Mahayana Buddhism

Chong Won Sa Korean Buddhist Temple

719 Lakehaven Drive, Sunnyvale

Facebook page

B-2.e: Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhism

Chua Giac Minh

763 Donohoe St., East Palo Alto

Web site 1 Web site 2

B-2.f: Mahayana Buddhism originating in other countries

B-3: Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana Buddhism was historically centered on the region around the Himalayas; but there are schools in other countries, e.g., Japan.

Bodhi Path Buddhist Center

2179 Santa Cruz Ave, Menlo Park

Web site

Karma Kagyu lineage, as taught by Shamar Rinpoche

Dechen Rang Dharma Center

1156 Cadillac Ct., Milpitas

Web site

Nyingma tradition, lineage of H.H. Jigme Phuntsok Rinpoche

Karma Thegsum Choling Buddhist Meditation Center

677 Melville Avenue, Palo Alto, CA

No Web site, phone 650-967-1145

B-3.a: Japanese Vajrayana Buddhism

Shingon Buddhist International Institute

Northern California Koyasan Temple

1400 U St., Sacramento

Web site

B-3.b: Other Vajrayana Buddhist lineages

Shambhala International: See New Religious Movements with roots in Indian Religions

C. Christian faith communities

The different divisions of Christianity is taken from the World Council of [Christian] Churches on its Web site here. Christianity is a wildly diverse religion, and local faith communities may belong to a group not listed here; or belong to two or more groups; or in some other way not fit into these divisions.

C-1: African Instituted Churches (or African Independent Churches)

A loose grouping of Christian churches that were organized by Africans and for Africans, in response to white missionary work on the continent of Africa. Beliefs and organizations vary widely. A few AIC churches have started congregations in North America.

Celestial Church of Christ (Aladura): Oakland Parish

4001 Webster Street, Oakland

Page on denominational Web site

The Church of the Lord (Prayer Fellowship) Worldwide: —

Zion Christian Church: —

C-2: Anglican churches

C-2.a: The Anglican Communion: The Anglican church began in England, splitting from the Roman Catholic church c. 1530. At the 1930 Lambeth Conference of Anglican churches, it was agreed that the Anglican Communion is a “fellowship, within the one holy catholic and apostolic church, of those duly constituted dioceses, provinces or regional churches in communion with the see of Canterbury.” Local Anglican churches range from “high church” or “Anglo-Catholic” congregations, where the services look a great deal like Roman Catholic services, to “low church” congregations, where the services are much simpler.

The Episcopal Church (USA): Originally the only Anglican denomination in the U.S., but recently some more conservative parishes have split away (see Convocation of Anglicans in North America below).

The Episcopal Church (USA): Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church

600 Colorado Ave., Palo Alto

Web site

The Episcopal Church (USA) oversees the vast majority of Anglican churches in the U.S.

C-2.b: Convocation of Anglicans in North America (Church of Nigeria, Anglican): “The Convocation of Anglicans in North America (CANA) was established in 2005 as a pastoral response of the Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) for Nigerian Anglicans living in the United States and Canada. In 2006, CANA began welcoming biblically orthodox American and Canadian Anglican parishes and clergy … [T]he resulting Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) is an emerging province in the Anglican Communion. CANA is a founding member of ACNA and enjoys close relationships with ACNA’s bishops, clergy, and congregations. The Diocese of CANA East was welcomed as a diocese in the ACNA in June 2013.” The “biblically orthodox” North American parishes referred to above split from the Episcopal Church (USA) primarily around ordination of women and lesbian and gay persons. The Province de l’Eglise Anglicane au Rwanda turned over jurisdiction of its North American parishes to CANA in 2015.

Anglican Church of the Pentecost

475 Florin Rd., Sacramento

Apparently a new church plant, using another church’s building. Web page on denominational Web site

C-2.c: Continuing Anglican churches: These churches are outside the Anglican Communion. In the U.S., they typically have split from the Episcopal Church (USA) to retain more conservative liturgies or practices.

Anglican Province of Christ the King: St. Ann Chapel

541 Melville Ave, Palo Alto

Web site

C-3: Assyrian Church

Though similar to other Eastern Christian churches, services of the Assyrian Church of the East differ in details. The liturgy is typically given in Aramaic, an ancient predecessor to the Syrian language.

Mar Yosip Parish

680 Minnesota Ave., San Jose

Web site

C-4: Baptist churches

Baptists tend to value congregational independence, so services and beliefs may vary widely.

C-4.a: American Baptist: American Baptists split from Southern Baptists during the period leading up to the Civil War. American Baptist beliefs vary widely, with some very conservative congregations, and some congregations that are more liberal than conservative Unitarian Universalist congregations.

First Baptist Church of Palo Alto

305 N. California Ave., Palo Alto

According to the Web site, “a welcoming, inclusive community of faith.” Web site

C-4.b: National Baptist Convention: A historically Black denomination.

Jerusalem Baptist Church

398 Sheridan Ave., Palo Alto

A historically Black church. Web site

C-4.c: Southern Baptist: One of the largest Christian groups in the U.S. Some Southern Baptist congregations are aimed at specific ethnic groups, e.g., the congregations below are aimed at Korean-Americans.

Avenue Baptist Church

398 Sheridan Ave., Palo Alto (in Jerusalem Baptist Church, above)

A new “church plant” with a Korean-American pastor. Web site

Southern Baptist: Cornerstone Community Church

701 E. Meadow Dr., Palo Alto

Self-described as “mostly comprised of Korean-Americans.” Web site

C-4.d: Primitive Baptist: Primitive Baptists use no musical instruments in their services. (Primitive Baptist Universalists, sometimes called the “No-Hellers,” constitute a sub-group of Primitive Baptists; they are not closely related to Universalists.)

Golden Gate Primitive Baptist Church

2950 Niles Canyon Road, Fremont

Web site | Facebook page

C-5: Disciples of Christ (Christian Church)

The Disciples of Christ seek to be inclusive of all Christians, and since they creeds as divisive they do not use creeds.

First Christian Church of Palo Alto

2890 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

C-6: Evangelical churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) Web site notes: “It took until the middle of the 1940s before a “new evangelicalism” began to emerge, which was able to criticize fundamentalism for its theological paranoia and its separatism. Doctrinally, the new evangelicals confessed the infallibility of the Bible, the Trinity, the deity of Christ, vicarious atonement, the personality and work of the Holy Spirit, and the second coming of Christ. These are the theological characteristics which are shared by the majority of Evangelical churches today in the world. The other distinctive feature is the missional zeal for evangelism and obedience to the great commission (Matthew 28:18-19).” The WCC further notes: “In regions like Africa and Latin America, the boundaries between ‘evangelical’ and ‘mainline’ are rapidly changing and giving way to new ecclesial realities.”

Within the U.S., the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) is one body that promotes cooperation among Evangelical churches. For member denominations of the NAE, see this Web page; most of these denominations are listed under other categories for the present listing.

See also: C-22: Non-denominational churches

C-7: Lutheran

According to the Web site of the Lutheran World Federation, “To be Lutheran is to be: Evangelical [i.e., they ‘proclaim the ‘good news’ of Christ’s life”]; Sacramental [i.e., they center their worship in both proclamation and celebration of the sacraments]; Diaconal [i.e., they believe in service to the world]; Confessional [i.e., they confess the Bible as the “only source and norm” for Christian life]; Ecumenical [i.e., they promote Christian unity].” Lutherans acknowledge their commonality with other Christians, and their uniqueness: “While the central convictions of the Lutheran tradition are not uniquely ours, its distinctive patterns and emphases shape the way in which we respond to the challenges and questions we face today.”

ELCA: Grace Lutheran Church

3149 Waverly St., Palo Alto

According to their Web site, “an inviting and diverse Christian community.” Web site

ELCA: First Lutheran Church

600 Homer Ave., Palo Alto

According to their Web site, “we welcome people diverse in sexual orientation and gender identity.” Web site

Missouri Synod: Trinity Lutheran Church

1295 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

No Web site.

C-8: Methodist churches

Methodism grew out of the reform movement started by John and Charles Wesley. “The Wesley brothers held to the optimistic Arminian view that salvation, by God’s grace, was possible for all human beings. … They also stressed the important effect of faith on character, teaching that perfection in love was possible in this life.” — World Council of Churches Web page on Methodist churches. The Wesley brothers wrote hundreds of hymns, some of which are among the most popular English-language hymns.

African Methodist Episcopal: St. James AME Church

1916 E. San Antonio St., San Jose

Facebook page

African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion): University AME Zion church

3549 Middlefield Rd. Palo Alto

Web site

Christian Methodist Church: Lewis Memorial Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

1363 Turlock Lane, San Jose

Facebook page

United Methodist Church: First United Methodist Church of Palo Alto

625 Hamilton Ave., Palo Alto

Web site

C-9: Holiness movement churches

Began as a reform movement within American Methodism in the early nineteenth century. “Instead of only some especially gifted persons in the church entering into a carefully disciplined life of holiness, all believers were to do this; they were to present themselves to God as living sacrifices in the midst of the regular routines of life.” — World Council of Churches Web page on Holiness churches.

The Salvation Army grew out of this movement, but it has a unique structure and mission, and is listed separately below.

Church of God (Anderson, IN): New Beginnings Church of God

1425 Springer Rd., Mountain View

Web site

Church of the Nazarene: Crossroads Community Church

2490 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

The Christian Holiness Partnership (CHP) is an international organization which facilitates cooperation between Holiness churches.

C-10: Moravian and Historic Peace Churches

A grouping of churches that all have a historic commitment to non-violence and peacemaking. “In 2013, the Moravian and Historic Peace Churches, including Mennonites, Brethren, — and Friends (Quakers), decided to be represented in the governing bodies of the WCC as one confessional family and gather as such during confessional meetings at WCC events.” — World Council of Churches Web page on Historic Peace Churches.

C-10.a: Church of the Brethren

(closest church is in the Central Valley)

C-10.b: Mennonites

Mennonite Church USA: First Mennonite Church of San Francisco

290 Dolores St., San Francisco

Web site

Old Order Amish: (closest community is in the Central valley)

U. S. Mennonite Brethren: Ethiopian Christian Fellowship

2545 Warburton Ave., Santa Clara

Page on denominational Web site

C-10.c: Religious Society of Friends (Quaker)

Friends General Conference (FGC):

Local Quaker meetings that are affiliated with FGC are often (but not always) unprogrammed meetings — that is, they have silent meeting for worship. The closest affiliated monthly meeting is in Sacramento.

Friends United Meeting (FUM): Berkeley Friends Church

1600 Sacramento St., Berkeley

Web site

Most Quaker meetings and Quaker churches affiliated with FUM are programmed meeting — that is, they have a sermon as well as unprogrammed time for spoken ministry. They tend to be more conservative theologically.

Other Quaker groups:

Pacific Yearly Meeting: Consists of liberal, unprogrammed meetings along the Pacific coast of North America, but is not affiliated with Friends General Conference.

Palo Alto Friends Meeting

957 Colorado Ave., Palo Alto

Web site

C-10.d: Unitas Fratrum, or Moravian Church

Moravian Church in America: Guiding Star Fellowship

Meeting location: 957 Colorado Avenue, Palo Alto (Palo Alto Friends Meeting)

Page on denominational Web site

C-11: New Church movement (Swedenborgianism)

Churches that draw inspiration from the writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg. “The life of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) was steeped simultaneously in the rational world of the physical sciences and a deep Christian faith.” — from the Web site of the Swedenborg Foundation

Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco

2107 Lyon Street, San Francisco

Web site

C-12. Old-Catholic churches

Catholic church bodies (mostly national churches) that separated from the Roman Catholic Church in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Clergy and bishops are permitted to marry; women may be ordained.

Ecumenical Catholic Communion: (closest church is in southern California)

Polish National Catholic Church: (closest church is in the Midwest)

C-13: Orthodox Churches (Eastern)

Eastern Orthodox Churches are distinguished from the Roman Catholic Church in a number of ways. First, Eastern Orthodox Churches do not recognize the supremacy of the Pope. Eastern Orthodox churches are organized into independent national churches or language groups, each under the leadership of a Patriarch; the Patriarch of Constantinople has a position as “first among equals” but does not have supremacy over the other Patriarchs.

Eastern Orthodox differ from Roman Catholics in other ways. The Eastern Orthodox do full immersion baptisms of infants, and children are also confirmed as infants, thus allowing them to partake of the eucharist (take communion). Many Eastern Orthodox churches venerate icons, and some of the most beautiful objects in Orthodox churches are the icons, pictures of saints. Unlike Roman Catholic priests, Eastern Orthodox priests may marry; women may become diaconesses (but not priests).

C-13.a: Antiochian Orthodox (Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America of the Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East)

The Antiochian Orthodox church “traces its roots to first century Antioch (modern-day Antakya, Turkey), the city in which the disciples of Jesus Christ were first called Christians (Acts 11:26),” according to their Web site. An excellent description of their services may be found here: http://www.antiochian.org/content/first-visit-orthodox-church-twelve-things-i-wish-id-known

Orthodox Church of the Redeemer

380 Magdalena Ave., Los Altos Hills

Web site

This congregation was originally affiliated with The Episcopal Church (USA), but beginning in 1960, “disturbed by the controversial teachings of Bishop Pike, which strayed from traditional Christian theology,” they eventually discovered the Antiochian Orthodox church and changed affiliations (as told on their Web site).

C-13.b: Armenian Apostolic Church

St. Andrew Armenian Church

11370 S. Stelling Rd., Cupertino

Web site

C-13.c: Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

The services are meant to be full of beauty, with many beautiful ritual objects, elaborate vestments (ritual clothing for those who preside at the worship service), and beautiful music. “Worship is not simply expressed in words. In addition to prayers, hymns, and scripture readings, there are a number of ceremonies, gestures, and processions. The Church makes rich use of non verbal symbols to express God’s presence and our relationship to Him. Orthodoxy Worship involves the whole person; one’s intellect, feelings, and senses.” — description of worship on the Archdiocese Web site Congregants stand for the entire 3-hour service.

Saint Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church

1260 Davis St., San Jose

Web site

C-13.d: Orthodox Church of America

Originally Russian Orthodox, but became independent in 1970. The services are much like the Greek Orthodox services (see above).

Nativity of the Holy Virgin Church

1220 Crane St., Menlo Park

Web site

C-13.e: Patriarchal Parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church in the USA (Russian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate)

These are the Russian Orthodox congregations that chose to remain under the administration of the Patriarch of Moscow, when the Orthodox Church of America was granted independence.

St. Nicholas Cathedral

2005 15th Street, San Francisco

Web site

C-13.f: Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia split from the Russian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate after the Russian Revolution of 1917, when the latter pledged support to the Bolsheviks.

St. Herman of Alaska

161 N. Murphy Ave., Sunnyvale

Web site

Traditional Russian Orthodox services are in Old Church Slavonic, an old language that is now only used for church services. In many Russian Orthodox services, everyone stands for the entire service (except those who are too old, or who have physical disabilities), and the services can last for 2-3 hours. While some people dislike standing that long, for others standing so long can bring on a meditative or ecstatic state of awareness.

C-13.g: Serbian Orthodox Church in North and South America

St. Archangel Michael Serbian Orthodox Church

18870 Allendale Ave., Saratoga

Web site

C-13.h: Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA

St. Michael Parish

345 7th St., San Francisco

Web site

C-14: Orthodox Churches (Oriental)

Each of the Oriental Orthodox Churches — Coptic, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Syriac, Armenian, etc. — is independent.

C-14.a: Armenian Apostolic Church (Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin)

St. Andrew Armenian Church

11370 South Stelling Rd., Cupertino

Web site

C-14.b: Coptic Orthodox

One of the most ancient Christian traditions — probably the oldest still-existing Christian group, dating back about 1,900 years — the Coptic Orthodox church is based in Egypt, and the Eritrean and Ethiopian Orthodox Churches are its “daughter churches.” According to the BBC, “Coptic services take place in the very ancient Coptic language (which is based on the language used in the time of the Pharaohs), together with local languages. The liturgy and hymns remain similar to those of the early Church” (link).

St. George and St. Joseph Coptic Orthodox Church

395 W. Rincon Ave., Campbell

Web site

C-14.c: Eritrean Orthodox

Eritrean Holy Trinity Orthodox Tewahdo Church of Santa Clara County

403 S. Cypress Ave., San Jose

Web site (mostly in English)

Web site (mostly not in English)

C-14.d: Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

Debre Selam St. Michael Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

1565 Lincoln Ave San Jose

Web site

C-14.e: Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

“The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church traces its origins back to the work of the Apostle St Thomas in the south-west region of India (Malankara or Malabar, in modern Kerala). … During the Portuguese persecution, the Indians who wanted to maintain their eastern and apostolic traditions appealed to several Oriental churches. Thus started the connection with the Syrian Orthodox Church of Antioch, in 1665. … in 1912, as a symbol of freedom, autocephaly and apostolic identity, the Catholicosate was established and an Indian Orthodox metropolitan was elected as the head (Catholicos) of the Malankara Church.” — World Council of Churches, Web page on Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

See: C-23.a: Mar Thoma church

C-14.f: Syriac Orthodox

St. Thomas the Apostle

1921 Las Plumas Ave., San Jose

Web page

C-15. Pentecostal churches

Pentecostal churches trace their roots back to the Asuza Street Revival, which took place in 1906 in Los Angeles. The name comes from the story of Pentecost, in the New Testament book of Acts, in which the spirit of God came into the followers of Jesus after Jesus’ death. Thus Pentecostals emphasize the workings of the Holy Spirit in the lives of human beings. Currently, Pentecostalism is perhaps the fastest-growing Christian group.

Some Pentecostal churches may include time for spiritual experiences like speaking in tongues, divine healing, etc. Many Pentecostal churches do not have such activities, but they do believe that each person can have a direct experience of God. Many Pentecostal groups are rightly proud of their racial diversity.

C-15.a: “Holiness” churches

“The earliest Pentecostals drew from their Methodist and Wesleyan Holiness roots, describing their entrance into the fullness of Christian life in three stages: conversion, sanctification, and baptism in the Spirit. Each of these stages was often understood as a separate, datable, ‘crisis’ experience.” — World Council of Churches, Web page on Pentecostal churches

Church of God in Christ: Abundant Life Christian Fellowship

2440 Leghorn St., Mountain View

A mega-church with average attendance of approx. 4,500 people per week. (An historically Black denomination, now racially diverse.) Web site

Church of God (Cleveland, TN): Redwood City Church of God

2798 Bay Road, Redwood City

Web site

International Pentecostal Holiness Church: The Father’s House

133 Bernal Rd., San Jose

Web site

C-15.b: “Finished work” churches

“Pentecostals, from the Reformed tradition or touched by the Keswick teachings on the Higher Christian Life, came to view sanctification not as a crisis experience, but as an ongoing quest.” — World Council of Churches, Web page on Pentecostal churches

Assemblies of God: Pathway Church

1305 Middlefield Rd., Redwood City

Web site

International Church of the Foursquare Gospel: Word of Life Foursquare Church

7160 Graham Ave., Newark

Web site

Redwood City Hispanic Foursquare Church / Centro CO3

3399 Bay Rd., Redwood City

Facebook page

C-15.c: “Oneness” or “Jesus’ Name” churches

In the the baptismal formula, “Oneness” Pentecostals use “the formula ‘in the Name of Jesus Christ’ recorded in Acts (cf. Acts 2:38).” — World Council of Churches, Web page on Pentecostal churches

Pentecostal Assemblies of the World: Christ Temple Community Church

884 San Carrizo Way, Mountain View

No Web site, phone: 650-965-7396

United Pentecostal Church: First United Pentecostal Church

878 Boynton Ave, San Jose

Web site

C-16: Reformed churches

The Reformed tradition has its roots in the Swiss reformation of John Calvin, Ulrich Zwingli, etc. Worship services emphasize sermons and the spoken word. Communion may happen monthly, quarterly, or on some other schedule, but there will rarely be communion every week. “There is no stress on a special elite person or group that has received through direct revelation or by the laying on of hands extraordinary powers of authority. … The level of education required for the Presbyterian or Reformed minister is traditionally high.: — World Council of Churches, Web page on Reformed churches.

C-16.a: Congregational

In congregational churches, each congregation is quasi-independent; there is la relatively flat ecclesiastical hierarchy. Congregations join together in local associations to provide mutual support and guidance; congregations also belong to national bodies or associations of congregations.

National Association of Congregational Christian Churches: Grace North Church

2138 Cedar St., Berkeley

Web site

United Church of Christ: See: C-21. United and Uniting Churches

C-16.b: Presbyterian

Presbyterians are governed by “courts,” groups or committees consisting of pastors and ruling elders “presbyters”). In the local congregation the “court” is called the “session”; at the regional level, the “court” is called the “presbytery”; the national or highest level, various presbyteries come together in a “synod.” This is a somewhat more formal structure than that of Congregational churches.

Presbyterian Church USA: First Presbyterian Church

1140 Cowper St., Palo Alto

Known as a liberal church with a social justice orientation. Web site

A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians (ECO): Menlo Park Presbyterian

950 Santa Cruz Ave., Menlo Park

Recently broke with Presbyterian Church USA to join a more conservative Presbyterian group. Web site

C-16.c: Reformed

Governed in much the same way as Presbyterian churches.

Reformed Church in America: New Hope Community Church

2190 Peralta Blvd., Fremont

Web site

Originally named the Reformed Dutch Protestant Church.

C-17. Restorationist churches

A grouping of loosely related churches, which in some way seek to restore the Christian church to earlier norms.

Latter-Day Saint movement, or Mormon churches: Founded by Joseph Smith, as a movement to restore Christianity to what it was during the time of Jesus and his followers. Most churches in the Latter-Day Saints movement accept the Book of Mormon, as revealed to Joseph Smith, as a scripture on a part with the Bible.

Community of Christ: Formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Community of Christ San Jose Congregation

990 Meridian Ave., San Jose

Web site

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon): The largest and best-known Mormon group. Local groups are lay-led (i.e., there are no professional clergy). Members in need can rely on their local Ward (or congregation) for food, financial support, etc.

Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints in Palo Alto

3865 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

They host the annual Christmas creche. 650-494-8899 No Web site

Jehovah’s Witnesses: “As Jehovah’s Witnesses, we strive to adhere to the form of Christianity that Jesus taught and that his apostles practiced.” — Jehovah’s Witnesses Web site Jehovah’s witnesses have many distinctive beliefs and practices, e.g., they do not celebrate Christmas or Easter; do not see Jesus as God; have communion only once a year; etc.

Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall

4243 Alma Street, Palo Alto

650-493-3020 No Web site

C-18: Roman Catholic

The Roman Catholic Church is perhaps the most familiar Christian body to many in the U.S., with its distinctive hierarchical organization, and its distinctive worship service, called the “mass.”

St. Thomas Aquinas Parish

3290 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

(English mass at 10:30 a.m.)

(Latin mass with Gregorian chant at 12:30 p.m.)

This parish has two other locations:

Our Lady of the Rosary Church

3233 Cowper St., Palo Alto, CA 94306

(Spanish mass at 9:30 a.m.)

St. Albert the Great Church

1095 Channing Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94301

There has been a long tradition in the U.S. of ethnic Catholic churches, where a Catholic church is formed to meet the needs of an ethnic group, often with at least some masses in a language other than English, and/or cultural references. Religiously, these are Roman Catholic churches; but with great differences in music and worship style (i.e., in the emotional dimension of religion). In many cases, now a single Catholic church will offer masses aimed at several different ethnic groups in several languages.

St. Joseph Parish

582 Hope St., Mountain View

Web site

This parish has masses in English, Spanish, Tamil; and bilingual English/Spanish.

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church

5111 San Felipe Rd., San Jose

Web site

Services in the Igbo language.

C-18.a: Eastern Catholic Churches

Eastern Catholic Churches are churches that were once affiliated with Oriental Orthodox or Eastern Orthodox Churches, but are now affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church. Eastern Catholic Churches typically have worship services that are more like Orthodox services than they are like Roman Catholic services.

St. Elias the Prophet Melkite Greek Catholic Church

4325 Jarvis Ave., San Jose

Web site

C-19: The Salvation Army

A Christian church with a unique organizational scheme, and a unique mission. The Salvation Army organizes itself on quasi-military lines, with the church hierarchy adopting military authority and titles. The mission of the church is strongly oriented to social justice, including help for the needy, disaster preparedness and relief, etc.

The Salvation Army: Redwood City Salvation Army

660 Veterans Blvd., Redwood City

In addition to other services, worship Sundays at 11:00 a.m. Web site

C-20: Seventh Day Adventist church

Seventh-Day Adventists hold worship services on the seventh day, i.e., Saturday. They grew out of the Millerite movement of the early nineteenth century.

Seventh Day Adventist: Seventh Day Adventist Church of Palo Alto

786 Channing Ave., Palo Alto

No Web site

C-21: United and Uniting Churches

C-21.a: United Church of Christ: Formed in 1957 as a merger of the Congregational Christian Church and the Evangelical and Reformed Church. The United Church of Christ is quite liberal, ordaining women, supporting same-sex marriage, etc.

First Congregational Church of Palo Alto

1985 Louis Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

C-20.b: International Council of Community Churches

Havenscourt Community Church

1444 Havenscourt Blvd., Oakland

Facebook page

C-22: Non-denominational churches

These are local faith communities that, for one reason or another, decline to affiliate with a larger denomination.

Peninsula Bible Church

3505 Middlefield Road, Palo Alto

Web site

Evangelical Christian; theologically, historically associated with premillennial dispensationalism.

Stanford Memorial Church

Web site

A deliberately non-denominational church with “Protestant Ecumenical Christian worship” that aims to serve the diverse religious community of Stanford University.

C-23: Other Christian churches

C-23.a: Mar Thoma church

This church traces its origins back to the year 52, when Thomas, one of the followers of Jesus, established Christianity in India. After splitting from the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in the 1950s, the church went its separate way. The worship services are designed to take “the worshipper out of the mundane world into the dimensions of spirit to worship in spirit and truth”: a full description of the service may be found here.

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church (Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar): Mar Thoma Church of Silicon Valley

3275 Williams Rd, San Jose

Web site

See also: C-14.e: Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

CC. Post-Christian communities

Post-Christian faith communities may defined as those communities that were once considered Christian, but which have diverged from Christianity to the extent that they can no longer be considered Christian. Some scholars class these groups with New Religious Movements, but this classification doesn’t work well. E.g., for Unitarians and Universalists, these groups started out in the 18th century as Christian groups, so they are clearly not new religions; yet they are no longer Christian.

CC-1: Unitarian Universalism

Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA)

505 E. Charleston Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

First Unitarian Church of San Jose

160 North Third St., San Jose

Web site

Sunnyvale UU Fellowship

1112 S. Bernardo Ave., Sunnyvale

Web site

Redwood City UU Fellowship

2124 Brewster Ave., Redwood City

Web site

D: Confucian communities

“What Westerners label ‘Confucianism’ is known by Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese followers as the ‘Scholarly Tradition.’ Confucianism does not have a strong institutional presence in [the United States], mostly because of the deep connection the tradition has had with the social and political structures of East Asia. For some, however, the scholarly values and symbols of Confucianism serve as important reminders of the cultural and philosophical legacy of their ancestors, and as relevant touchstones for thinking about ethics and modern life in the United States.” — The Pluralism Project of Harvard University

D-1: Confucian temples

No known Confucian temples in the United States.

D-2: Confucius Church

Founded in China by Chen Huanzhang in 1912, a number of Confucius Churches were established in the Chinese diaspora, including in the United States. They combine the Confucian practices and worldview with Western-style church organization.

Salinas Confucius Church

1 California St., Salinas

No Web site; phone 831-424-4304

I can find no evidence of recent activity at the Salinas Confucius Church, so I am also including the following:

Confucius Church of Sacramento

915 4th St., Sacramento

No Web site, phone 916-443-3846

N.B.: The Confucius Institutes at Stanford and other universities are not faith communities, but rather a scholarly group dedicated to promoting Chinese culture and language. Web page of Stanford group

E: Daoist (Taoist) faith communities

Daoist temples may be dedicated to a specific Daoist deity, such as Guan Yin. Many Daoist temples have been set up by Asian immigrants, and in these temples adherents may carry out rituals and practices passed down over the generations. There are also a few Daoist groups organized by persons of Western descent, and these are more likely to practice their religion based on their own interpretations of Asian texts and practices.

Kong Chow Temple

855 Stockton St., San Francisco

Dedicated to Guan Di. Wikipedia page

Ma-Tsu Temple of U.S.A.

30 Beckett St., San Francisco

Web site

Tian Yuan Taoist Temple

509 28th Ave., San Mateo

No Web site, phone: 650-578-8568

Tin How Temple

125 Waverly Place, San Francisco

Web page on Chinatownology Founded in 1852, probably the oldest extant Chinese temples in the Bay Area (the oldest Chinese temple in California is in Weaverville).

F. Hindu faith communities

Hinduism is a complex religion, that includes many different deities and many different practices. “The peoples who today call themselves “Hindus” have many forms of practice, both in India and around the world. The brahmins of Banaras and the businessmen of Boston, the ascetics and yogis of the Himalayas and the swamis of Pennsylvania, the villagers of central India and the householders of suburban Chicago—all have their own religious ways.” — Harvard University Pluralism Project

But there are religious assumptions held by most Hindus: “the universe is permeated with the Divine, a reality often described as Brahman; the Divine can be known in many names and forms; this reality is deeply and fully present within the human soul; the soul’s journey to full self-realization is not accomplished in a single lifetime, but takes many lifetimes; and the soul’s course through life after life is shaped by one’s deeds.”

Geographically, Hindus are a majority in India, Nepal, and Bali (in Indonesia). Countries with a significant Hindu presence include Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Fiji.

In the U.S., Hindu temples may have a variety of deities, or a given temple may be devoted to only one or two deities.

Hindu Temple and Community

450 Persian Dr., Sunnyvale

Web site

Variety of deities.

Shirdi Sai Darbar

255 San Geronimo Way, Sunnyvale

Web site

See also: K-5.a through K-5.e for New Religious Movements originating in Hinduism.

G: Islamic faith communities

Muslims may consider Islam to be non-sectarian. Yet some Muslims also find discernible sectarian differences. The different types of Islam here are taken from Salatomatic.com, which designates types simply as a way for practicing Muslims to determine where they might feel most comfortable praying.

G-1: Sunni

Yaseen Foundation (Muslim Community Assoc. of the Peninsula)

Mosque: 621 Masonic Way, Belmont

Community center: 1722 Gilbreth Road, Burlingame

Web page on Salatomatic | Web site

G-1.a: Barelwi Sunni

—

G-1.b: Hanafi Sunni

—

G-1.c: Deobandi Sunni

—

G-2: Shia

G-2.a: Ismaili Shia

—

G-2.b: Bohra Ismaili Shia

Anjuman-e-Jamali

998 San Antonio Road, Palo Alto

Web page on Salatomatic | Related Web site

The Dahwoodi Bohra are primarily from a region of India. They have distinctive dress for both men and women.

G-2.c: Jafari Shia

Masjid Al Rasool

552 South Bascom Ave., San Jose

Predominantly Persian. Web site on Salatomatic

G-3: Sufi

G-3.a: Naqshbandi-Haqqani Sufi

Jamil Islamic Center

427 S. California Avenue, Palo Alto

Web page on Salatomatic

G-3.b: Jerrahi Sufi

—

G-4: “Non-denominational”

There are a number of “nondenominational” Muslim groups in the U.S. These often have formed because there are too few Muslims to have separate groups.

Taha Services Masjid

1285 Hammerwood Ave., Sunnyvale

Predominantly Indian/Pakistani. Web page on Salatomatic

Muslim Community Association

3003 Scott Blvd., Santa Clara

Web page on Salatomatic (called the “largest and most active” mosque in the Bay Area) | Web site

L: Jain faith communities

Jainism is best known for the principle of ahimsa, which may be translated as non-violence, or as doing no injury to other living things. Lay Jains are typically vegetarians, so as to prevent them from doing injury to other beings. Monks take ahimsa further than that: wearing cloths over their mouths to prevent them from inhaling and thus harming small insects; not eating vegetables such as carrots where harvesting the vegetable kills the plant; etc. There are two main divisions of Jains: “white-clad,” in which the monks wear distinctive white garments; and “sky-clad,” in which the monks reduce possessions to a minimum by not even owning or wearing clothing.

Jain Center of Northern California

722 S. Main St., Milpitas

Web site

I: Jewish faith communities

Jews trace their history back for thousands of years, but contemporary “rabbinical Judaism” emerged from “Temple Judaism” after the Romans destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. The Jewish sabbath lasts from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. Worship services involve reading from the Torah, in Hebrew.

I-1: Orthodox

Generally more conservative in practice and belief. In Orthodox synagogues, men and women are often seated separately. Only men may be rabbis.

Congregation Emek Baracha

4102 El Camino Real, Palo Alto

Web site

I-2: Conservative

The name “Conservative” means that this group aims to conserve Jewish tradition, while bringing into alignment with modernity. Conservative Jews affirm the religious equality of women, and women may become rabbis.

Kol Emeth

4175 Maneula Ave., Palo Alto

Web site

I-3: Reform

A liberal religious Jewish group that is often aligned with Unitarian Universalists on social issues.

Congregation Beth Am

26790 Arastradero Rd., Los Altos Hills

Web site

I-2,3: Conservative and Reform

Congregation Etz Chayim

4161 Alma St, Palo Alto

They “meld Reform and Conservative traditions.”

Web site

I-4: Reconstructionist

Reconstructionist Jews hold that Jewish law and custom should be aligned with modern thought and life. Very liberal in terms of both practice and belief, many Reconstructionist Jews interpret Jewish practices broadly, and may not adhere to traditional theism.

Keddem Congregation

Most services are at Kehillah Jewish High School, 3900 Fabian Way, Palo Alto

According to their Web site, “Reconstructionist Judaism may be considered a ‘maximalist liberal Judaism’.”

Web site

J: Native religions and cultural traditions

In the Bay area, this will include the religion of the Ohlone people; it may also include the religion of other Indian tribes or First Nations or indigenous groups, when people of those groups have settled in the Bay Area.

Scholar Stephen Marini distinguishes between “high sacred rituals of tribal religion” and expressions of “traditional spirituality on social occasions.” Marini further points out that inter-tribal powwows are a type of social occasion, “a public ritual gathering of one or more clans or tribes dedicated to skill competitions, feasting, and dancing” where outsiders can experience first-hand the power of Native sacred song, dance, etc. See: Stephen Marini, Sacred Song in America (University of Illinois Press, 2005), p. 18.

Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS)

Web site

Organization for LGBTQ natives. Sponsors annual powwows in San Francisco.

Berkeley Indigenous Peoples Day Powwow and Market

Web site

Annual powwows in October (Columbus Day weekend), for nearly 25 years.

Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations (SKINS)

San Francisco State University

Facebook page

Sponsored a powwow in 2016; check http://calendar.powwows.com for future events.

K. New Religious Movements

The categories in this section are taken from Christopher Partridge, New Religions: A Guide: New Religious Movements, Sects, and Alternative Spiritualities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). There is a huge diversity of New Religious Movements, and just a few examples are given for the categories below; see Partridge’s book for additional examples.

K-1: New religions with roots in Christianity

Church of Christ, Scientist: Christian Scientists do not have paid clergy. Instead, lay people known as Readers lead their worship services. The Readers read from Christian Science texts, and from the Bible. There are set readings for each week of the year. The congregation also sings hymns during worship services. Services take place on Sundays and Wednesdays. At the Wednesday services, members of the congregation may give testimonials about how their faith has helped them in their life, including how their faith has helped them cure physical ailments. Christian Scientists avoid most medical care, believing that physical ailments can be cured through religious practice.

First Church of Christ, Scientist

3045 Cowper St., Palo Alto

Web site

Unity: A combination of Christianity and “New Thought,” Unity uses insights from all world religions, sort of like Unitarian Universalists, but they still consider themselves Christian. They place an emphasis on meditation, which is always part of their services.

Unity Palo Alto

3391 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto

Web site

Some scholars consider the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints a New Religious Movement; see C-17. above.

Some scholars consider the Jehovah’s Witnesses a New Religious Movement; see C-17. above.

Some scholars consider the New Church a New Religious Movement; see C-11. above.

K-2: New religions with roots in Judaism

Some scholars consider Reconstructionist Judaism a New Religious Movement, see I-4. above.

K-3: New religions with roots in Islam

Nation of Islam: Muhammad Mosque No 26

5277 Foothill Blvd., Oakland

Facebook page

Some scholars consider Baha’i a New Religious Movement; see section A. above.

K-4: New religions with roots in Zoroastrianism

—

K-5. New religions with roots in Indian religions

K-5.a: Vedanta Society: Founded in 1895 by Swami Vivekananda, the Vedanta Society is arguably the oldest form of institutional Hinduism to be established in North America. It was affiliated with the Ramakrishna Order of India.

Vedanta Society of San Jose

1376 Mariposa Ave, San Jose

Web site (shared with 2 other Bay Area Vedanta Societies)

K-5.b: Self-Realization Fellowship movement: Founded in 1925 by Swami Yogananda in Los Angeles. Since then, has split into several different groups.

Ananda Church of Self Realization: Ananda Palo Alto

2171 El Camino Real, Palo Alto

Web site

This faith community bases its practices Hinduism, and they trace back to a Hindu teacher, Yogananda. But they also consider Jesus Christ a holy person. Yoga is a part of what they do.

K-5.c: ISKCON [International Society for Krishna Consciousness]: Founded in 1965 by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, and known informally as the Hare Krishna movement.

ISKCON of Silicon Valley

1965 Latham Street, Mountain View

Web site

ISKCON Silicon Valley has a charitable free meals distribution program called “Free Veg Meals for All”; more info here.

K-5.d: BAPS: “Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) is a socio-spiritual Hindu organization with its roots in the Vedas” (link).

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir

1430 California Circle, Milpitas

Web site

K-5.e: Brahma Kumaris: Started in the 1930s by “Om Baba,” this group sees its mission as primarily spiritual education.

Mediatation Center

821 Anacapa Court, Milpitas

Facebook page Denominational Web site

K-5.f: Dhammakaya Foundation: Originating in Thai Buddhism, the movement is noted for their form of meditation known as Dhammakaya meditation.

Dhammakaya Meditation Center Silicon Valley

280 Llagas Rd., Morgan Hill

Web site

K-5.g: Shambhala International: Followers of the teachings of Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

Shambhala Meditation Center of San Francisco

1231 Stevenson St., San Francisco

Web site

K-6: New religions with roots in East Asian religions

Cao Dai: a syncretic Vietnamese religion founded in the 1920s.

Cao Dai Temple of San Jose

947 S. Almaden Ave., San Jose

Predominantly Vietnamese language. Web site

Jeung San Do: A syncretic religion that is part of the Chungsan family of Korean religions: “The Chungsan family of religions is neither Buddhist nor Confucian nor Christian; nor is it simply an organized form of Korea’s folk religion. … The Chungsan religions are distinguished…by the unique god they worship [who is addressed as Sangjenim] and the unique rituals they say their god has told them to perform.” — Don Baker, “The New Religions of Korea,” Korean Spirituality (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), p. 85.

Jeung San Do dojang

3419 Grand Ave. #202, Oakland

No Web site, phone: 408-709-0045

Rissho Kosei-kai: A liberal New Religious Movement from Japan based on Buddhism with approx. 3 million adherents. Included here primarily because Rissho Kosekai and UUism had strong ties in the 1960s-1970s.

Rissho Kosei-kai of San Francisco

1031 Valencia Way, Pacifica

Web site

Shinnyo-en Buddhism

3910 Bret Harte Drive, Redwood City

Web site for the whole denomination (no separate Web site for the Redwood City location)

Based on Buddhism, founded in Japan in the 20th C.

Soka Gakkai International (SGI): Based on Nichiren Buddhism, a branch of Japanese Buddhism, SGI claims approx. 20 million adherents.

SGI-USA Silicon Valley

1875 De La Cruz, Santa Clara

Web site

Tenrikyo: “Tenrikyo has drawn influences from many religious traditions, but it displays many distinctly Shinto themes.” — Ian Reader, Esben Andreasen, and Finn Stefansson, “The New Religions of Japan,” Japanese Religions Past and Present (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1993), p. 122.

Tenrikyo Cupertino Fellowship

880 Chesterton Ave., Redwood City

No Web site, phone: 650-366-4971; listing on denominational Web site

K-7: New religions with roots in indigenous and pagan traditions

Native American Church: Originating the the Plains States in the late nineteenth century, combines Native American traditions with Christian elements.

Medicine Path Native American Church

Once you register for a ceremony, they send you the location

Web site

Neo-Pagan and Wiccan: A diverse group, some of whom are solo practitioners, others of whom gather into small groups. There is no standardization, but many Wiccans and Neo-Pagans have ceremonies on the solstices and equinoxes, as well as on the “cross-quarters.” Many Neo-Pagan groups are quite small, some Neo-Pagans experience discrimination; thus these groups may remain secretive.

South Bay Circles

Meet at various locations

Web site

Some scholars consider Santeria, Candomble, and Vodou to be New Religious Movements. See section L. below.

K-8: New religions with roots in Western esoteric traditions

Spiritualism: Spiritualists believe that it is possible to communicate with those who have died. National groups include National Spiritualist Association of Churches. Listed here because in the late nineteenth century, some prominent Universalists became Spiritualists, and through the twentieth century some Unitarians and Universalists held spiritualist beliefs.

National Spiritualist Association of Churches: Golden Gate Spiritualist Church

1901 Franklin St., San Francisco

Web site

K-9: New religions with roots in modern Western cultures

Ethical Culture Society: Ethical Culture Society: Unitarian Universalism and Ethical Culture Society have historical connections; some local congregations are affiliated with both Ethical Culture and UUism. Some observers have termed Ethical Culture a “post-Jewish” religion (analogous to a “post-Christian” religion like Unitarian Universalism).

Ethical Culture Society of Silicon Valley

Meet in member’s homes and other locations.

Web site

Humanist communities: Some Humanist communities may have originated as splinter groups from UU congregations.

Humanists in Silicon Valley

1180 Coleman Ave., San Jose

Web site

Sunday Assemblies: A new group similar to Humanists. Calling themselves “a secular community service organization,” they have monthly “assemblies” that loosely resemble Protestant or Evangelical Christian services (congregational singing, a light rock band, etc.) but with no mention of a deity or the supernatural.

Sunday Assembly Silicon Valley

Meets at various locations.

Web site

L: Orisa devotion

A syncretic religion, combining aspects of Yoruba and perhaps other African religious traditions with Western traditions. A central feature of this extremely diverse religious tradition is Orisa devotion; an orisa (also spelled orisha or orixia) is a deity that is one embodiment of the ultimate deity.

Adherents of Orisa devotion may avoid contact for a variety of reasons. For example, speaking of Santeria, Michael Atwood Mason, author of Living Santeria: Rituals and Experiences in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst. Press, 2002) writes, “…immigrants to the United States have often hidden their involvement in the religion in an attempt to assimilate themselves into American soceity. Within the religion itself, secrecy also protects ritual knowledge.” (p. 9). Anthony Pinn, in Varieties of African American Experience (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 1998) points out that when Vodou came to New Orleans it was characterized as “evil,” and public celebrations were banned.

About Botanicas: A botanica is a store that sells supplies for practitioners of Orisa devotion, and often for other traditions as well. Followers of Orisa devotion may not belong to formal religious organizations, and/or may not welcome contact (see above). However, the Harvard Pluralism Project lists botanicas as religious centers for this religious tradition; a botanica may host or sponsor classes or events or ceremonies.

Terminology: The term “Orisa devotion” is used here as being the most inclusive; this follows in the scholarly tradition of books such as Orisa Devotion as World Religion ed. Jacob K. Olupona and Terry Rey (University of Wisconsin Press: 2008). The Harvard Pluralism Project calls this “Afro-Caribbean” religion, a term which may exclude African-trained Yoruba practitioners in the U.S., and/or Brazilian Candomble practitioners. Scholar of religion Stephen Prothero calls this “Yoruba religion,” though other West African peoples such as the Fon also venerated Orisas.

L-1:Yoruba tradition (origins in contemporary Nigeria and West Africa)

—

L-2: Santeria (origins in Cuba)

Botanica El Trebol

“Santeria, Orishas…”

1864 W San Carlos St., San Jose

Web site

La Sirena Botanica

1918 Brewster Ave., Redwood City

Yelp page

L-3: Vodou (origins in Haiti)

L-3.a: Hatian Vodou

Legba’s Crossroads

“Haitian Vodou services and supplies” based in San Francisco; the store is onlin, though, so no publicly accessible bricks-and-mortar location in SF

Web site

L-3.b: Louisiana Vodou

—

L-4: Candomble (origins in Brazil)

—

M: Other traditions, including Shinto

M-1: Shinto

“Originating in Japan’s prehistory, Shinto is the Natural Spirituality or the practice of the philosophy of proceeding in harmony with and gratitude to Divine Nature. The Shinto Shrine is an enriched environment where we can feel deeply refreshed and renewed.” — Web site of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America (Seattle) In the U.S., there are half a dozen Shinto shrines in Hawai’i, and one in Seattle, according to a 2010 blog post titled “Shinto Shrines Worldwide Outside of Japan,” on the Shinto: Faith of Japan Web site.

M-1.a: Konkokyo (a sect of Shinto), Konko Churches of North America: “Kami and Us, completing each other, Live the Faith! Konkokyo (the Konko Faith) is a belief system characterized by an accepting and non-judgmental view of humanity. It teaches belief in a divine parent (called Tenchi Kane No Kami) who is the life and energy of the universe —

indeed is the universe — as well as a loving parent who wishes only the happiness and well-being of all human beings, the children.” — Konko Church Web site

Konko Church of San Jose

284 Washington St., San Jose

Page on denominational Web site

N: Sikh faith communities

Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak in northwestern India, which in his day included both Hindus and Muslims; Nanak was famous for saying there are neither Hindus nor Muslims, implying that all persons have access to the divine. Many Sikh gurdwaras (temples) are devoted to providing food to anyone who needs it, and many gurdwaras have a communal meal after the service that is open to anyone.

Types of Sikh communities are taken from W. H. McLeod, Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

N-1: “Orthodox” Sikhs

Gurdwara Sahib

3636 Murillo Ave., San Jose

Web site

N-2: Nirankari Sikhs A reform movement, which recognizes Baba Dayal as a renewal of the line of Gurus, without, however, disputing the orthodox doctrines of (a) the succession of the first ten Gurus, and (b) the presence of the eternal Guru in the sacred scripture.

N-3: Namdhari Sikhs A reform movement which holds to a different succession of Gurus than do the orthodox; distinctive ritual and dress.

Nihang: a quasi-military order; not different in belief from orthodox Sikhs, the Nihangi are typically unmarried so that they might devote themselves to defending the Khalsa.

O: Zoroastrian faith communities

An ancient religion, originating in Persia. Central rituals involve fire. Note that non-Zoroastrians are NOT allowed in Fire Temples.

San Jose Darbeh-Mehr

10468 Crothers Rd., San Jose

Web site

This list of faith communities is from:

Neighboring Faith Communities: A Process Guide

A curriculum for grades 6-8

Compiled by Dan Harper, v. 0.8.3

Copyright (c) 2014-2016 Dan Harper