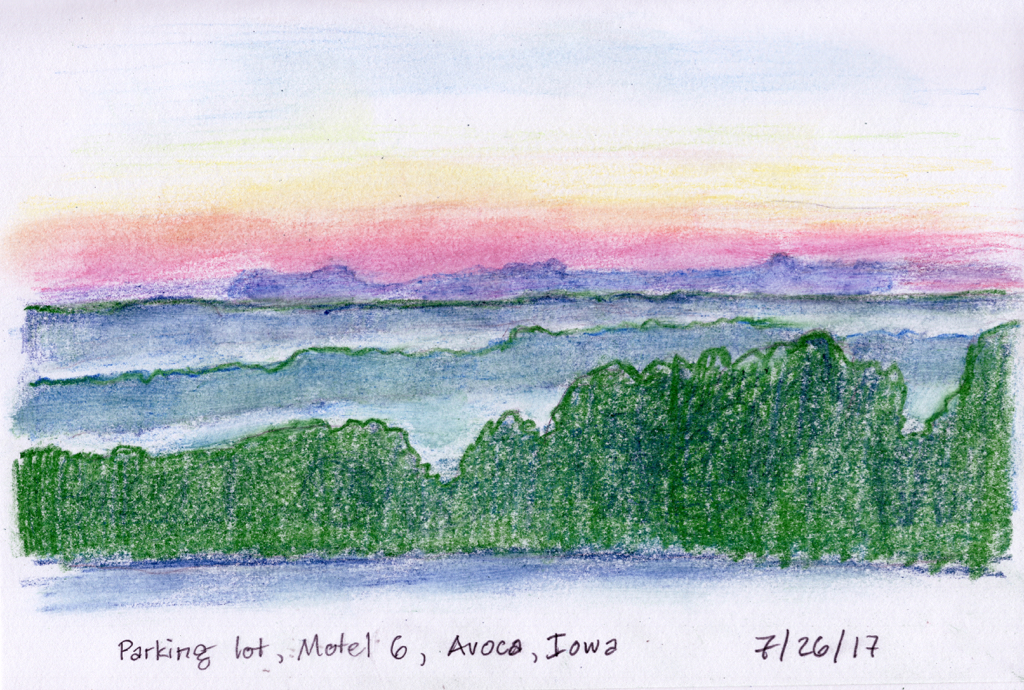

In the motel parking lot this morning, two women were re-packing the car next to mine, while a toddler sat quietly in the back seat, sucking at a bottle of milk. One of the two women was a couple of years older than I, and she was moving from South Carolina to Portland, Oregon, to be near her daughter — the other woman in the car — and her grandson — the toddler. So the car was full of her belongings. I told her that I had been in Massachusetts helping my sister dispose of the last of my father’s belongings, so my car was full of stuff, too. We got into a long talk about moving, and people dying, and other such mournful topics that are so satisfying when you get into your fifties, while the young woman pretty much ignored us, and worked on repacking the car. We said something to her about how she probably found this kind of talk boring, and she politely refrained from rolling her eyes and said something noncommittal. Her mother said, “She’s in her twenties, she’s still young.” I said to the young woman, “I’ll bet you don’t feel young.” “No,” she said, “I don’t.”

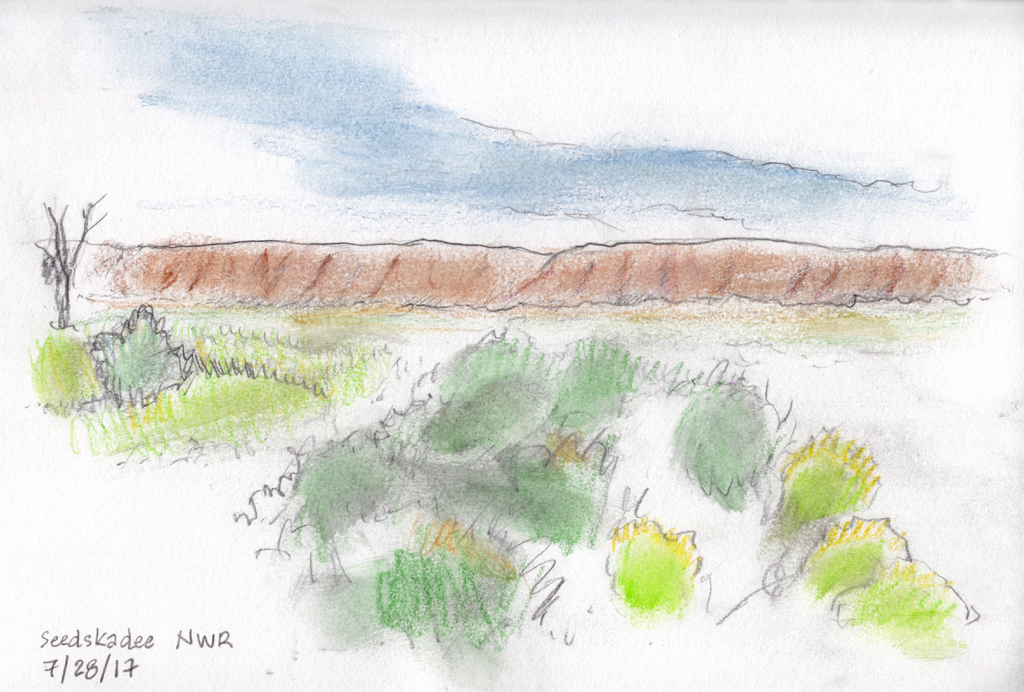

I drove all day, and at about six o’clock pulled into one of the several entrance roads to Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge. I had thought about going to someplace new and different, but after being so disappointed with yesterday’s visit to a new and different place I decided I’d go to a place I knew I liked. I walked a mile and a half down a dirt road alongside the Green River, looking out at the marshes and trees along the edges of the river. And then I walked back, this time looking in the opposite direction, out over the sage brush and up at the heavily eroded bluffs a mile or so back from the river. Some Sage Sparrows flew over my head, singing their funny little tsee-tsit-sit song as they went over.

It’s certainly not a wilderness experience. The county highway is a mile away but you can see it clearly over the flat sage plain; and the huge white above-ground infrastructure for Ciner Wyoming, a company that mines soda ash, is clearly visible ten miles to the south. But there is something very satisfying about the swift Green River, and its verdant marshes and trees, flowing in the middle of the arid sage brush plains, with steep bluffs well back from each side of the river, and in the far distance glimpses of snow-covered mountains. There is something about the elevation, something like seven thousand feet above sea level, and the dryness of the air, and the clarity of vision that comes with both these things. And there’s something about the sage brush, and the big ant hills among the sage, and the rocky alluvial soil under the sage.

The sun began to move lower in the sky, and I knew I had to leave. Some day, I promised myself, some day I’ll come back and spend a week or two here — but I don’t feel any need to keep that promise; it was enough to just think about it.