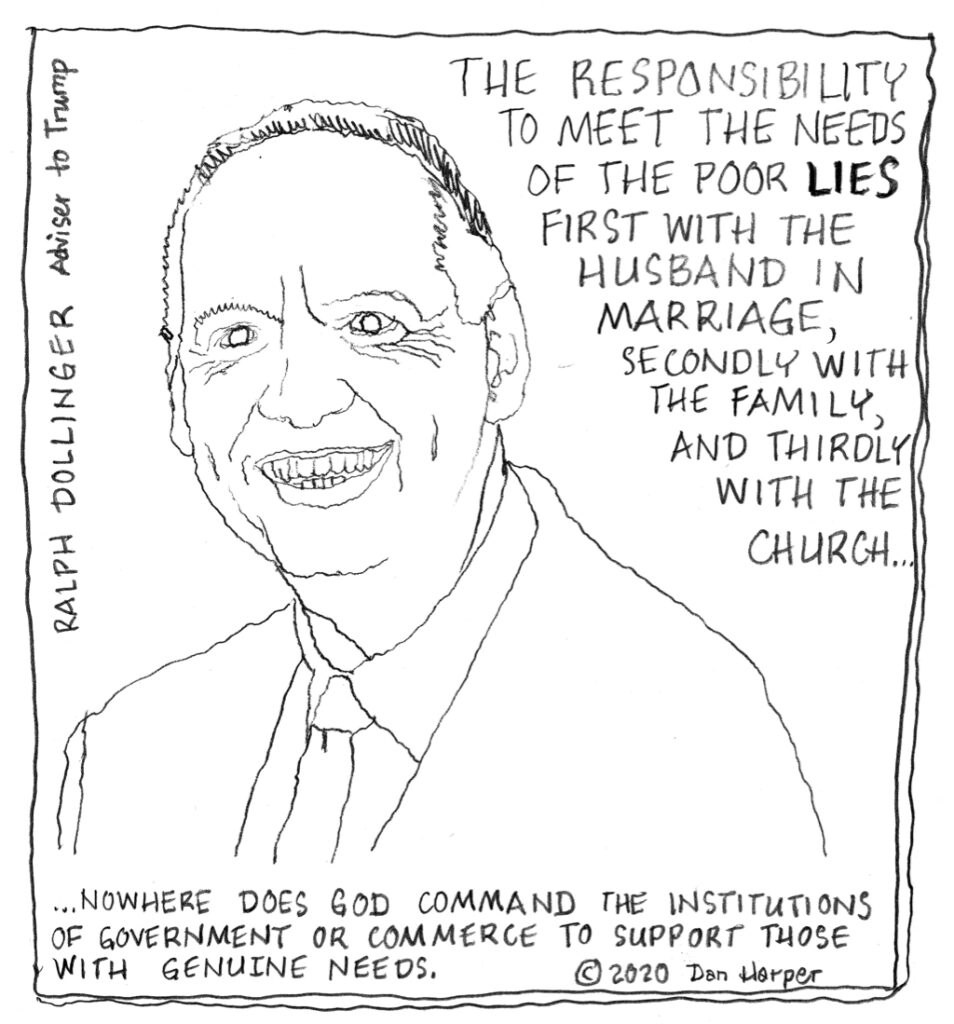

Ralph Drollinger, former professional basketball player and now the leader of Capitol Ministries in Washington, D.C., leads Bible studies for old white guys in power. He can boast that 11 of the 15 members of Trump’s cabinet attend his Bible study. According to the journalist Katherine Stewart, Drollinger should be identified more with politics than religion; specifically, with a political movement Stewart calls “Christian nationalism.” In a recent interview, Stewart quoted Drollinger on the subject of responsibility to the poor:

“The responsibility to meet the needs of the poor lies first with the husband in marriage, secondly with the family, and thirdly with the church. Nowhere does God command government or commerce to support those with genuine needs.”

This sounds to me as though Drollinger is telling rich men that if they will only support their wives and family and maybe give something to their church — beyond that, Drollinger is giving them permission to ignore the poor. Which reminds me of a story in the book of Mark about someone very like Ralph Drollinger who went to Jesus to ask a question:

“As Jesus was setting out on a journey, a man ran up and knelt before him, and asked him, ‘Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?’ Jesus said to him, ‘Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. You know the commandments: “You shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not bear false witness; You shall not defraud; Honor your father and mother.”‘ He said to him, ‘Teacher, I have kept all these since my youth.’ Jesus, looking at him, loved him and said, ‘You lack one thing; go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.’ When he heard this, he was shocked and went away grieving, for he had many possessions.”

If Ralph Drollinger will go and sell everything he owns, and give the money to the poor, then I’ll be willing to listen to his thoughts about supporting poor people. Until then, I’m going to ignore his cold-blooded and heartless words, and I’m going to continue in the tradition of my New England forebears who believed that one of the key roles of government was, in fact, to support those in need.