Some links from my recent web browsing:

Are We Allies?

Foluke Ifejola Adebisi has an excellent blog post on “the concept of allyship against injustice.” In other words, what does it mean to be a “white ally,” or any other kind of ally? Adebisi makes an intersting disctintion between allyship as being, and allyship as doing:

“I think what is important is that we move away from thinking of allyship as something we are, but instead think of it as something we do, each time we do something. Each time we want to contribute to a particular struggle for justice, we must decide what must be done in the moment, irrespective of what we have done before or what type of person we think we are.”

I came away from this blog post thinking that if I hear someone saying they are an ally, this may not mean much. I’m going to watch what they do instead of listen to what they say they are.

Jew or Judean?

Marginalia hosts a scholarly debate on how to translate ioudaioi in texts from the last centuries BCE and the first few centuries CE. Does it mean Jew or Judean? While this may seem like a big argument over a trivial detail, the scholars involved claim the stakes are higher than you’d think.

For example, if you translate ioudaioi in the Gospel of John as “Jew,” then that could reinforce one of the foundations of Christian anti-Semitism. The ioudaioi, the Jews, killed Jesus. Whereas if you translate ioudaioi as “Judean,” someone from the land of Judea, maybe you can undermine that foundation of anti-Semitism.

But other scholars argue that in some texts, ioudaioi is better translated into modern English as “Jew,” sometimes as “Judean.” It all depends on the context. And we don’t want to inject anachronisms into translations.

Another point comes up: Is it anachronistic to talk about Judaism as a religion in this era? Was Judaism more of an ethnic identity than a religion? (In a related story, Haaretz reports on archaelogist Yonatan Adler’s new book that advances the claim that the archaelogical record does not show evidence for Jusdaism as a religion before the 2nd century BCE.)

Dare You Fight?

Editor Neal caren is creating an online collection of W. E. B. DuBois’s articles for The Crisis. These articles were written between 1914 and 1934, and many have not been collected previously.

DuBois’s essays are fascinating to read. His articles for The Crisis sounds radical even by today’s standards.

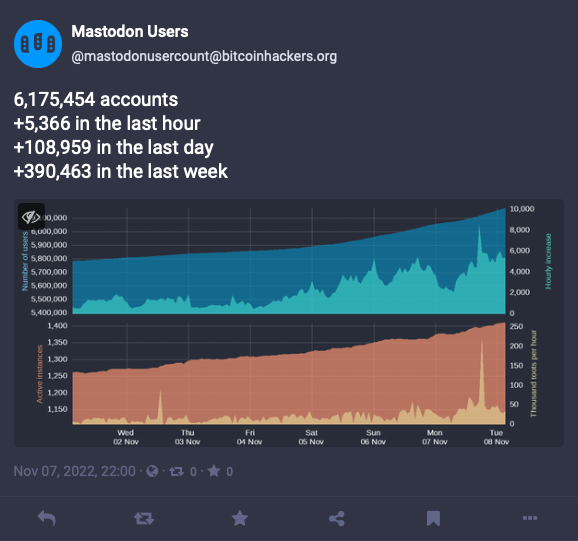

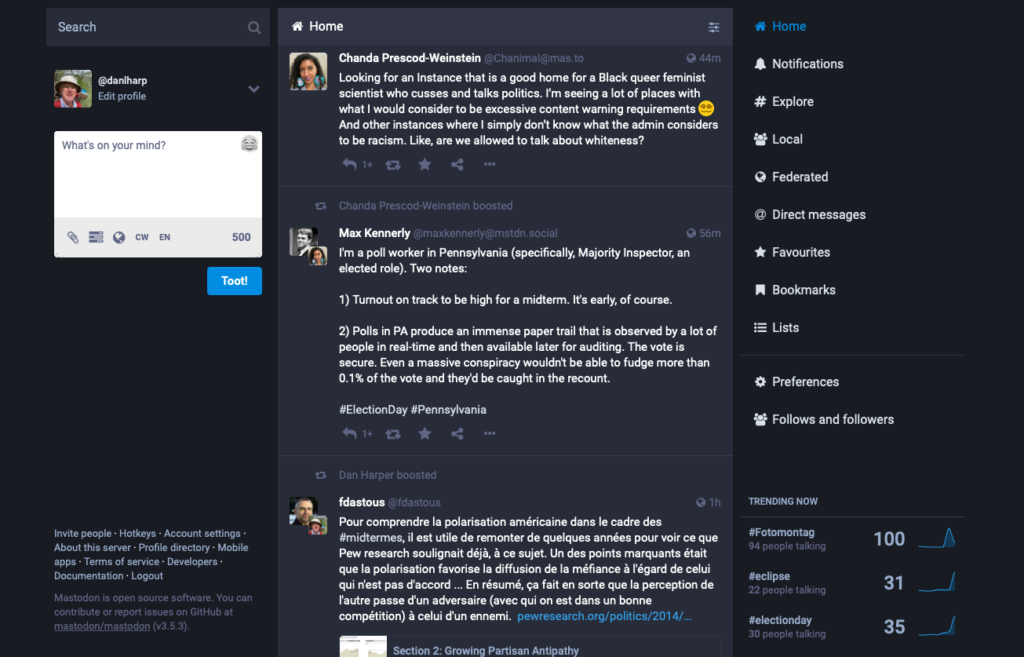

Invasion

Australian librarian Hugh Rundle writes about the exodus of people from Twitter to Mastodon. He titles his blog post “Home invasion: Mastodon’s Eternal September begins.” As a Mastodon user of fairly long standing, he describes how he has experienced the influx of Twitterers:

“It’s not entirely the Twitter people’s fault. They’ve been taught to behave in certain ways. To chase likes and retweets/boosts. To promote themselves. To perform. All of that sort of thing is anathema to most of the people who were on Mastodon a week ago…. To the Mastodon locals it feels like a busload of Kontiki tourists just arrived, blundering around yelling at each other and complaining that they don’t know how to order room service.”

Although I’m most emphatically not a Twitter user (I left Twitter in 2014, not in 2022), I am a new Mastodon user. I hope the Mastodon users don’t see me as behaving badly….