Is the famous song “This Little Light of Mine” an African American spiritual? Or was it composed by Harry Dixon Loes and Avis B. Christiansen around 1920?

Attributions to the African American tradition

Many hymnals and songbooks attribute “This Little Light of Mine” to “African American Spiritual,” or more generally to “Traditional.”

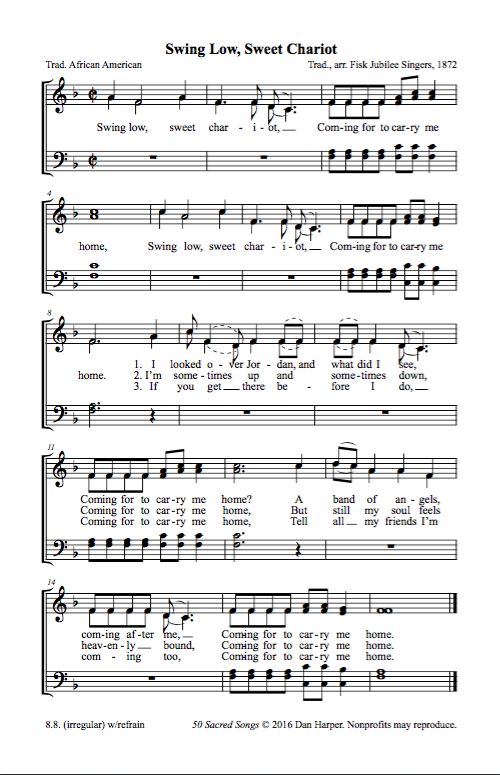

An influential source: Lift Every Voice and Sing II: An African American Hymnal, ed. Horace Clarence Boyer (New York: Church Publishing, 1993), has the following attribution: “Words: Traditional. Music: Negro spiritual, adapt. William Farley Smith (b. 1941)”. The melody of this version resembles the melody collected in 1939 by Alan Lomax, as sung by Doris McMurray of Huntsville, Texas.; this recording is available online here.

An equally influential source is Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs by Guy and Candie Carawan (Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 1963/2007). The Carawans give a somewhat different melody, and attribute this as “Traditional song” (p. 21). They provide documentary evidence that indicates the song was included in the “Highlander Song Book” (p. 25), a songbook that would date from the 1930s. Incidentally, the Carawans provide a bridge that is not included in the hymnals I’ve consulted.

In addition to the audio recording by folklorist Alan Lomax in 1939 (see above), “Let hit shine” was collected by Ruby Pickens Tartt, and published in “Honey in the Rock”: The Ruby Pickens Tartt Collection of Religious Folk Songs from Sumter County, Alabama (Mercer University Press, 1991, p. 5; words only). Note that like the Lomax version, this version was probably collected in the 1930s. The editors do not provide any guidance as to when Tartt collected this particular song, but they provide the following editorial comment, without documentation: “Widely performed by choirs and gospel groups during the 1930s, a favorite on gospel radio shows, ‘Let hit shine’ is now also in white folk tradition.”

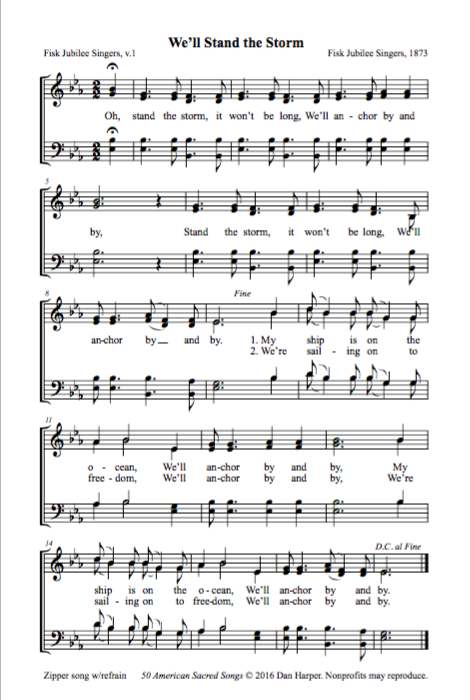

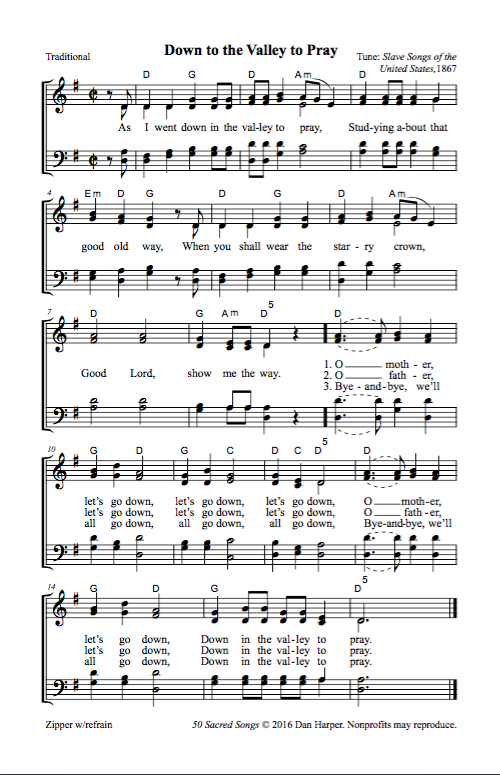

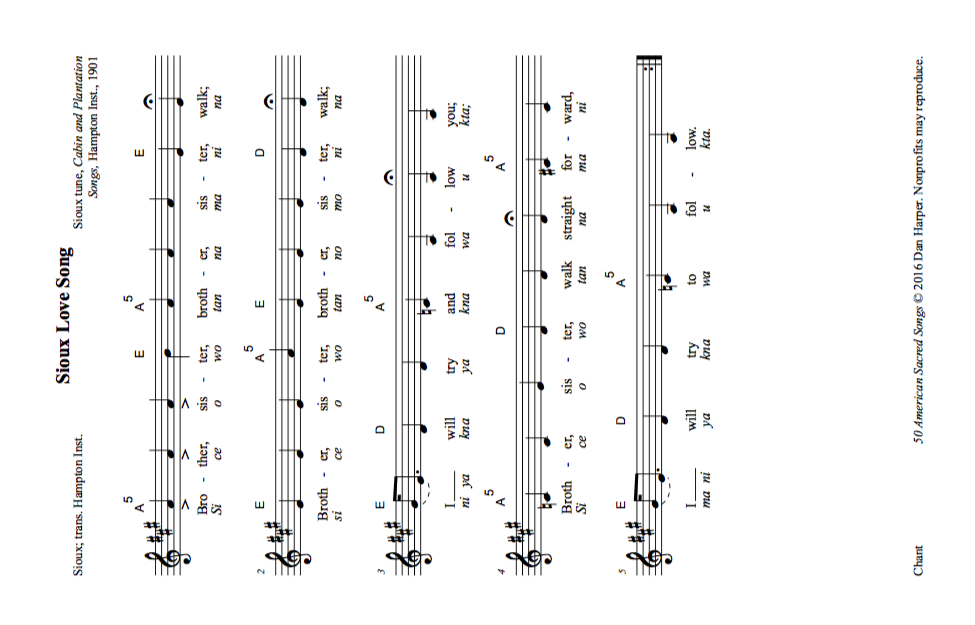

Note that “This Little Light” is NOT found in the following influential nineteenth century collections of African American songs: Slave Songs of the United States ed. William Francis Allen et al.; The Story of the Jubilee Singers; with their Songs (6th ed., 1872); Cabin and Plantation Songs as Sung by the Hampton Students (1876).

Attributions to composer Harry Dixon Loes

The words to “This Little Light” are collected by Steven Gould Axelrod, Camille Roman, and Thomas J. Travisano, in their book The New Anthology of American Poetry: Modernisms, 1900-1950 (Rutgers University Press, 2005), on p. 605. The editors add the following editorial comment: “Harry Dixon Loes (1892-1965) wrote and composed this song with Avis B. Christiansen (b. 1895). The pair also wrote the hymns ‘Blessed Redeemer’ and ‘Love Found a Way’.” This attribution, coming as it does from a well-regarded university press, carries some weight; however, the attribution is not documented.

Typical of the stories told about the song is that told by Ace Collins, in his book Music for Your Heart: Reflections from Your Favorite Songs (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2013), p. 191: “During his studies [at the Moody Bible Institute], Loes was struck by the significance of three different references to light in the New Testament…. Using light as an inspiration and coupling it to a melody that carried the feel of a spiritual, Loes wrote ‘This Little Light of Mine.’ Yet the song, which is today almost universally known, took a while to take off. Although written in 1920, it would be in the days just before World War II that churches began to adopt ‘This Little Light of Mine’ as a part of Sunday school programs. Within a decade, Loes’s song was translated into scores of languages and sung all over the globe.” Collins provides no documentation whatsoever for any of these assertions.

Although the song was supposedly composed c. 1920, I was unable to find a reference to it in the Catalog for Copyright Entries for the years 1920 and 1921; however, Loes might have copyrighted the song later than 1920.

Hymnary.org shows no publications in hymnals prior to about the late 1930s; see graph here. However, Hymnary.org does not include every single U.S. hymnal from the twentieth century.

Wikipedia attributes the song to Loes, but does not document the source for this attribution. The Wikipedia page was created July 26, 2007, and many online sources (and probably many print sources) unquestioningly accept the Wikipedia attribution in spite of the lack of documentation; therefore, be wary of any source published 2007 and later that attributes the song to Loes.

The Web site Hymntime.com does NOT list “This Little Light” as one of Loes’s compositions. Note that Hymntime.com gives Loes’s dates as October 20, 1892 to February 9, 1965; the birth year is different from the birth year given by Wikipedia.

Conclusion and questions

The fact that folklorists collected the song after Dixon’s purported composition date of circa 1920 indicates that the song could have passed quickly into the folk repertoire soon after composition. However, assuming Loes did indeed write the song (or if Loes co-wrote it with Christiansen), where and when was it first published?

If Loes wrote the melody, what was his original version? Similarly, if the melody is an African American spiritual, what is the earliest recorded version of the melody?

Loes was white, so if he wrote the song, how did it become associated with the African American tradition?

In the absence of firm answers to these and other questions about the origins of this tune, the most careful attribution for this song would be “Unknown.”