Helen Katharien Kreps was a Unitarian theological student who died of influenza in 1919.

She was born Oct., 1894, in North Dakota, when her father was based at Fort Totten, then on the Indian frontier. Since her father was a military officer, the family moved frequently in her first ten years; her younger brother was born in Nebraska, and in 1900 the family was living near San Diego.

At the time of the 1906 earthquake, her father was based in Fort McDowell, Calif., though it is not clear if his family was with him. The family must have been in Palo Alto for at least part of 1910, for Helen attended the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto when Rev. Florence Buck was filling in for Rev. Clarence Reed. Helen, then in high school, was deeply influenced both by Unitarianism, and by seeing Florence Buck, a woman, in the pulpit.

Later in 1910, Helen and her family were living at Cape Nome, Alaska. But Helen returned to Palo Alto to enter Stanford in the 1911-12 academic year. She worked as a filing clerk in the Stanford library beginning in 1912. While at Stanford, Helen majored in German, and participated in the summer, 1914, session of the Marine Biological Library. She was elected president of the Stanford English Club.

In 1915, she graduated from Stanford with high honors, and worked in the Stanford library in 1915-1916. She taught the first and second graders in the Sunday school at the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in that same year. She made regular financial contributions to the church in 1916, after which the notation “discontinued thru removal” (meaning she moved away) appears under her account.

In the fall of 1916, Helen entered the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry. There she showed impressive intellectual gifts. Earl Morse Wilbur, the president of the school, also remembered Helen’s exceptional character:

“Quiet and modest in bearing though she was, never asserting herself or her views, yet we instinctively felt that in her there was depth and breadth of character, and as she moved about among us she won a respect and exerted an influence that belong to few. I remember saying to myself at the end of her first chapel service, in which the depth and sincerity of her religious nature were revealed, that I should count myself happy if she might sometime be my minister; and those who were present at the devotional service which she conducted at the Conference at Berkeley last spring will not soon forget the impression she then made.”

During the summer of 1918, Helen supplied the pulpit of the Unitarian church in Santa Cruz, returning to the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry in the fall. She was well on her way to receiving her degree summa cum laude, when the world-wide influenza epidemic struck the Bay Area in October, 1918. In March, 1919, Earl Morse Wilbur reported the following in the Pacific Unitarian, the West Coast Unitarian periodical:

“It happened that Miss Kreps and Miss [Julia] Budlong [another theological student] had last year both taken a University course in Red Cross nursing; and when the emergency call came for nurses to care for the hundreds of victims on the campus they both volunteered without a moment’s hesitation. It was expected that the trouble would be over and that they would return to work within two weeks. Instead they paid as dearly for their patriotic service as many soldiers have done. Both were soon stricken with the influenza. … Miss Kreps’s case developed a dangerous attack of pneumonia, and for weeks her life hung in the balance; and she is even yet in the military hospital in San Francisco, slowly regaining her strength, and will be unable to return to her studies before next autumn….”

But Helen did not recover, and in the same month, March, 1919, the Pacific Unitarian carried Earl Morse Wilbur’s obituary for Helen, who had died Feb. 23, 1919, at the Letterman General Hospital in the San Francisco Presidio.

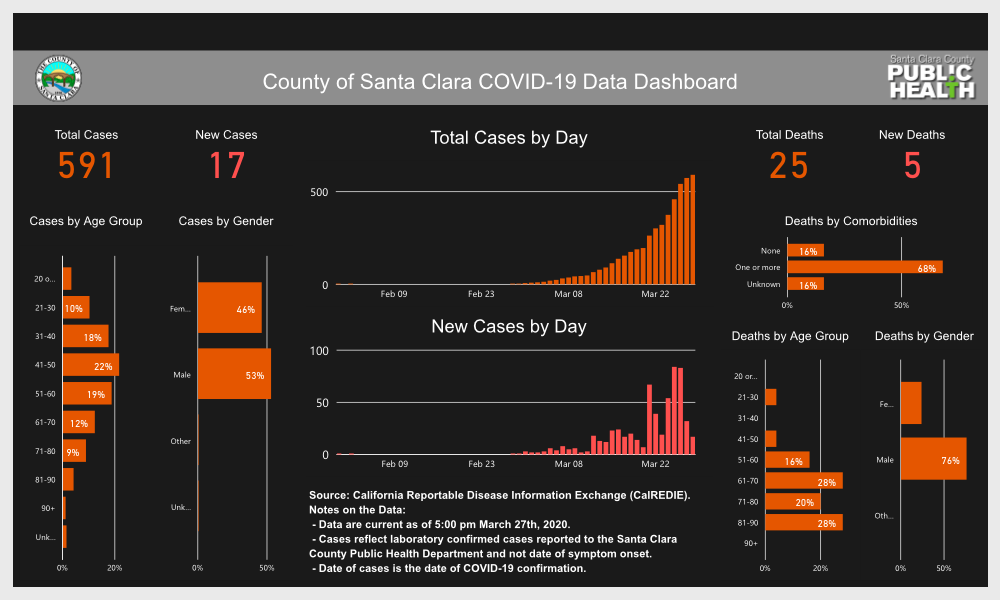

Her death is an example of what we hope will not happen during the current pandemic: we hope we don’t wind up with well-intentioned but barely trained people serving as nurses in makeshift hospitals, hospitals hastily set up to deal with an overwhelming number of sick people.

Notes: 1900, 1910 U.S. Census; M.H.T., “Jacob F. Kreps,” West Point Assoc. of Graduates, http://apps.westpointaog.org/Memorials/Article/3011/ accessed Nov. 18, 2016; Annual Registers, Stanford University, 1912-1915; Stanford Daily, Dec. 3, 1914; Earl Morse Wilbur, “Our School for the Ministry,” Pacific Unitarian, March 1919, p. 63; Earl Morse Wilbur, “Helen Katharine Kreps,” Pacific Unitarian, March 1919, pp. 65-66; Stanford Daily, Feb. 25, 1919.