After five years of the same look, I’m finally updating this blog. The new appearance is the most obvious change, but I’m also gradually updating some of the static pages as well.

Author: Daniel Harper

Concord Hymn

Sung at the Completion of the Battle Monument, April 19, 1836

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

The foe long since in silence slept;

Alike the conqueror silent sleeps;

And Time the ruined bridge has swept

Down the dark stream which seaward creeps.

On this green bank, by this soft stream,

We set today a votive stone;

That memory may their deed redeem,

When, like our sires, our sons are gone.

Spirit, that made those heroes dare

To die, and leave their children free,

Bid Time and Nature gently spare

The shaft we raise to them and thee.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson

One of the better poems Emerson wrote: simple and direct, and more complex than it seems at first; not unlike the five-minute battle which both the poem and the Battle Monument commemorate. The “votive stone” still stands in the same place that it stood when Emerson’s poem was sung to it back in 1836, 182 years ago today.

Above: The monument as it appeared at the 2009 re-enactment of the Battle of the North Bridge

Mindfulness and the elite

From my files: Three years ago, the New York Times Magazine published an article by Virginia Heffernan on the craze for mindfulness (“Mind the Gap,” 19 April 2015, pp. 13-15). Citing a Time magazine cover story that called the craze a “revolution,” Heffernan comments:

“If it’s a revolution, it’s not a grass-roots one. Although mindfulness teachers regularly offer the practice in disenfranchised communities in the United States and abroad, the powerful have really made mindfulness their own, exacting from the delicate idea concrete promises of longer lives and greater productivity. In January [2015], during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, [mindfulness popularizer Jon] Kabat-Zinn led executives and 1 percenters in a mindfulness meditation meant to promote general well-being.” But, notes Heffernan, “what commercial mindfulness may have lost from the most rigorous Buddhist tenets it replaced: the implication that suffering cannot be escaped but must be faced.”

Three years on, mindfulness is even more firmly entrenched among the elites. I recognize that there are serious Buddhist practitioners out there who teach authentic Buddhist mindfulness practices, and I also recognize that there are those who use mindfulness-stripped-of-Buddhism for benign ends. But when I think about how the 1 percenters have adopted mindfulness, I am curious about how it became so widespread among the “cultured despisers of religion.” Is the ongoing craze for mindfulness an example of how consumer capitalism can strip all the authentic weirdness out of religion, turning authentic religious practices into “opiates for the masses”? Or is mindfulness similar to the Christian “Prosperity Gospel,” that is, authentic religious teachings co-opted to promote consumer capitalism? except where the Prosperity Gospel is used to control lower middle class suckers, Prosperity Mindfulness is to control professional class suckers.

I am also curious whether authentic Buddhist mindfulness will survive being co-opted by the 1 percenters and consumer capitalism. What Heffernan calls “commercial mindfulness” really is nothing but an opiate: a pill that numbs us to the stress and horror and absurdity of an increasingly unjust economic system, but doesn’t actually cure the underlying illness of injustice.

To paraphrase Morpheus in the movie The Matrix: “If you swallow the blue pill of mindfulness, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe; but if you take the red pill of skepticism, you can see the wool that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth….”

Talking Proselytizer Blues

Here’s an old talking blues I found in my files, cleaned up a bit, and added chords to. It might be hard to figure out the rhythm in places, so I’ve italicized the main beats.

Walking down the street one fine summer day

A young man stopped me ’cause he had something to say:

“If you want to get to heaven when you up and die,

“You better come to my church, going to tell you why:

“You’re an old man… Time to turn to Jesus…

“We’ll help save you… Make you right with God.”

I said to him, “Kid, you might be right,

“But I think that you and I are fighting different fights:

“I’m fighting to save the world and I’m fighting to save the land;

“Your kind of saving I don’t really understand.

“But God and me go way back… Jesus too…

“And who you calling old… Young whippersnapper…”

“You’ll be damned,” he said mournfully,

“If you don’t stop your sinful ways and follow me!”

That’s all he could say. I feel kind of bad,

But I laughed at him, and he walked away mad.

I let him go… Sad kind of fellow…

Never smiled once… Depressed…

Now that poor fellow, when he up and dies,

He’s going to get one hell of a surprise,

Saint Peter’s going to ask him, “Kid, what did you do?

“Did you fight for peace and justice, the environment, too?

“Say what?… Mostly proselytized?

“Gee, that’s too bad… Say hi to Lucifer for me…”

As for me, when I up and die,

Saint Peter’s going to be the one who gets a surprise,

I’ll march right past him, headed straight on down,

Fight for peace and justice there under the ground.

Organize the damned… Unionize the devils…

Roll the bosses over… Turn hell into heaven…

If we want to get to heaven, here’s what we’re going to do:

Going to fight for peace and justice, maybe sing about it too;

Going to stop climate change so we don’t get barbecued;

And if folks need to eat then we’re going to get them food.

That’s the path to heaven… Clean air and water…

Social justice… And plenty of food…

D – G – /

A7 – D – /

D – G – /

A7 – D7 – /

G7 – – – /

A7 – – – //

(c) 2018 Dan Harper (with thanks to Ted Schade and the New Bedford Folk Choir, 2009)

Amar Chitra Katha

Someone in our congregation lent me a copy of a comic book biography of the life of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. Aimed at middle readers, I think it would work for older kids (and adults) too — a concise, easy-to-understand summary of Guru Nanak’s life and principles.

That comic book is published by Amar Chitra Katha, a publisher with over 400 comic books on hand, with titles like “Guru Nanak,” “Buddha,” “Buddhist Tales” and “More Buddhist Tales,” “Kalidasa,” and “Rabindranath Tagore” (the Nobel prize winning poet much beloved of mid-twentieth century Unitarians).

The one I really want to get is the forthcoming title “Valiki’s Ramayana,” a 960 page graphic novel treatment of the Ramayana. Most of us in the West know far too little about this major Indian religious work — and most of us aren’t going to read the full Ramayana, so I’d love to structure an adult education course around this graphic novel.

Amar Chitra Katha has lots of comics that would work great for children and youth, too. They have a U.S. branch, so the prices are pretty reasonable.

Game development

In our congregation, we decided we need to pay more attention to resources that can support the curriculums. We want resources that are fun for kids, don’t feel like weekday school, don’t require any teacher preparation, and support the learning that takes place in the regular curriculums.

Like, for example, board games and card games. We already use a couple of board games in our Sunday school: (1) Wildcraft, a cooperative board game that teaches about herbs, supports some of our ecology courses; and (2) Moksha Patam, a board game that simulates karma, rebirth, etc., supports one of our world religions curriculums.

Ideally, we’d like to have one relevant board game per quarter per age group that we can give to teachers. And while we were talking this over in the curriculum review committee, I started dreaming up a card game about Moses leading the Israelites to freedom across the wilderness. Then I had a day of study leave today, so I could prototype this game, provisionally called: “Exodus, The Card Game.”

The game borrows its basic structure from the classic card game Mille Bornes (if you don’t know Milles Bornes, it will be easier to understand this blog post if you first read the Wikipedia article).

Although I’m borrowing the basic structure of the game from Mille Bornes, there are significant differences. Mostly, Exodus is a faster-paced game, more suited to the short time allotted to Sunday school classes. And I had to make other changes to fit the narrative of the book of Exodus — I wanted to make sure that as you play you get some sense of the narrative of Exodus…such as the fact that G-d released fiery serpents that attacked the Israelites, but then G-d told Moses to make a brass serpent that would heal serpents bites (Num. 21:6-8). Before researching this game, I didn’t even remember about the fiery serpents. It’s a pretty strange thing to include in the narrative, and one of my learning goals (and part of my theological interpretation) for Exodus, The Card Game is to help kids understand that the story of Exodus is pretty weird. It’s not trying to be an accurate historical account, nor is it some kind of scientific explanation — rather, it is a narrative filled with fantastical elements that reveal G-d’s character.

My other big learning goal and theological component for the game is, not surprisingly, to give some understanding of G-d’s character. First and foremost, G-d is not all kittens-and-rainbows, as for example when G-d sends the fiery serpents to bite the Israelites. Second, G-d does not follow human logic and is ultimately unknowable by humans; this is symbolized for the Israelites in part by spelling G-d’s name without vowels: “YHWH” (this idiosyncratic spelling is retained in the game in the English name for G-d). Third, while G-d is not omnibenevolent, G-d does want justice for humans and for the land; this theological interpretation of G-d’s character is communicated by the social justice flavor of the G-d Given Right Cards. A lesser fourth point is that G-d’s power do have some limits to them; G-d is not wholly omnipotent. So it is the game tries to help the players get a small sense of G-d’s character.

If I ever put the game into production, I’ll let you know how you can get a copy….

Update 4/14/18: Major revisions to game rules and narrative now complete. I won’t revise this post any more; any future rules revisions will be incorporated into the production game (if it’s ever put into production).

Update 9/7/18: The game is now available as a professionally-produced card game, so I’m removing the outdated rules and card designs. To see the final game, click here.

Define “human”

What does it mean to be human? It is the fashion in liberal theology today to state that humans are embodied beings; we are not just some disembodied soul temporarily trapped in flesh; rather, you can’t separate our being from our flesh. If you want to leave any transcendent reality out of this definition, you might wind up defining humans as the entirely biological product of evolution; extreme versions of this would say that humans are nothing more than DNA that wants to replicate itself.

Now consider the fact that less than half of the cells in your body carry your human DNA. In article posted today, the BBC reports on the latest research about the human microbiome; latest estimates hold that only 43% of the cells in your body carry your DNA; the rest are “bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea.”

This would imply that to be an embodied human means, not that you are a solitary organism, but rather you are an ecosystem. In fact, the boundaries of your ecosystem may be less well defined than you have thought. Indeed, the latest thinking in medical science is that we might want to begin monitoring the information stored in the DNA of all those organisms. The BBC quotes Rob Knight, professor at the University of California San Diego:

“It’s incredible to think each teaspoon of your stool contains more data in the DNA of those microbes than it would take literally a ton of DVDs to store. At the moment every time you’re taking one of those data dumps, as it were, you’re just flushing that information away.”

“Data dumps”? Ah yes, the Brits do seem to find ways to include poop jokes where you least expect it. But seriously, this seems to bring us back to that older definition of what it means to be an embodied human, but with a twist: to be an embodied human is still to be a collection of information encoded on DNA; but now there’s a lot more information, not just from humans but also from archaea, bacteria, viruses, etc.

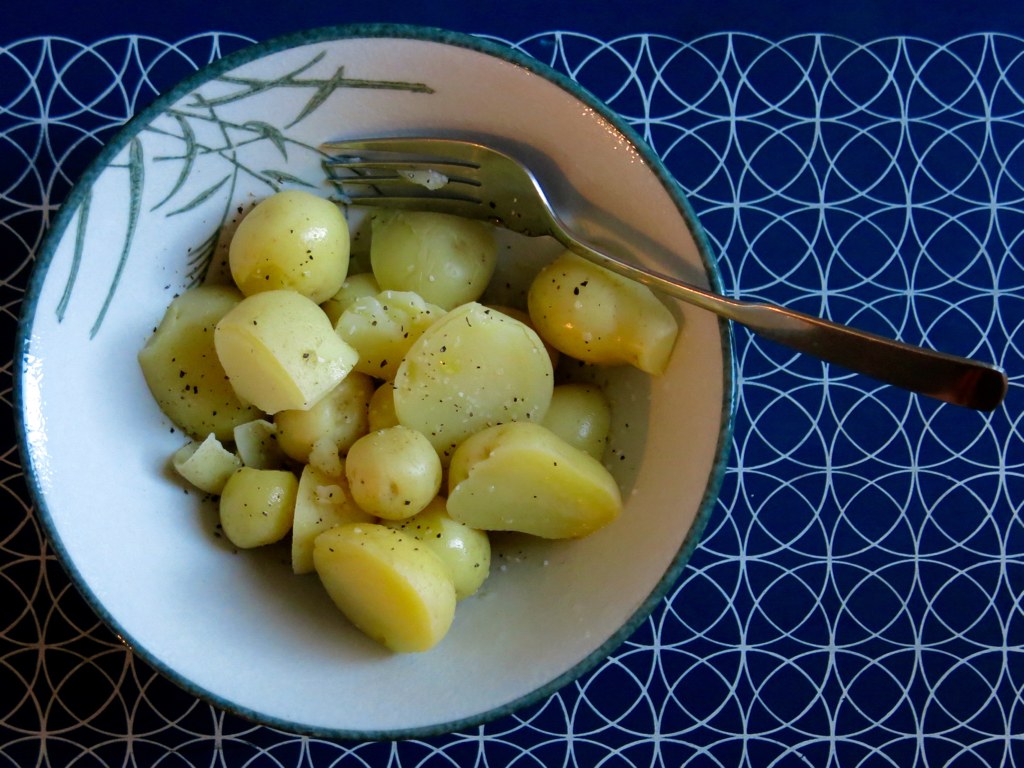

New potatoes

We planted a four foot row of potatoes right after we moved in to our new place, back in November. Something ate most of the leaves from the plants, and they slowly withered and died. This evening, Carol said we should look to see if there were any potatoes. I turned the heavy black soil over with a spading fork, and she sifted through looking for potatoes. We wound up with about a pound and a half of new potatoes. I took them in to the kitchen and carefully scrubbed them, trying to keep as much of the tender skin as I could.

When they were washed, I cut up the larger ones. I put them in a pot of simmering water for a few minutes. We served them with nothing more than some olive oil, a little kosher salt, and a sprinkling of black pepper.

Less than an hour after we pulled them out out of the soil, we were eating them. They tasted wonderful: faintly earthy, with a delicate texture.

Things I’ve dreamed of doing but have never done

1. Go to Labrador and take the mail boat up and down the coast: I grew fascinated with Labrador in my teens when I read an old book I think once belonged to my father, or maybe his father: The Lure of the Labrador Wild by Dillon Wallace. At 19, my first full time job was yardman in a lumberyard, and on coffee breaks I used to sit and talk with the dispatcher, Robin R., about where we wanted to travel; I always wanted to go to Labrador. I even went so far as to get a road map of Labrador, but there was no way I ever could have afforded to travel that far.

I still can’t afford to go to Labrador, but even if I could I’m not sure I want to go, not now. Now Labrador is far less remote: there’s a road to Goose Bay, and the coastal communities have much more contact with the outside world. I still want to go to the Labrador of 1980, but that’s impossible.

2. Live in Paris for six months: In my mid-twenties, I was still working at the lumberyard, now as a salesman. I was making more money by now, and arranged to spend one vacation in London and Paris. I took French classes to prepare for the trip, but when I got to Paris I realized how little of the language I knew. A friend of mine, William J., was living in Paris then. I dreamed of saving up my money and living there myself and studying French.

The unexpected ending to this story: When I went to Europe, I flew on Icelandair, and the flights stopped in Rekjavik. There was no jetway in those days, so you walked down those rolling stairs and across the tarmac to the terminal while they serviced the plane. I told a friend, Eddie J., how beautiful Iceland looked — and how beautiful the women were. At that time, Eddie worked seven days a week for six months each summer and fall painting houses, then spent the other six months of the year skiing in the Alps. The next winter instead of going skiing in the Alps, he went to Iceland, met an Icelandic woman, fell in love, married her, and as far as I know still lives there.

3. Publish a science fiction story: I met Mike F. in my first year of college. We were both science fiction fanatics, and we started a science fiction club. Mike was a good friend, but I felt competitive with him because he was a better writer than I; we talked about who would publish a science fiction story first, though I was pretty sure it would be him. A decade later, in an abortive attempt to get a master’s degree in writing, I learned that I am unable to write convincing fiction; I dropped out of that graduate program and went to work for a carpenter (working as a carpenter was then a dream of mine), and have never bothered to try to write fiction again.

The unexpected ending to this story: Mike and I both wound up working as clergy, and we both wound up doing a lot of online writing. In the 1980s, Michael became a rabbi and by the 1990s was known as the rabbi who wrote on America Online; I finally got ordained in 2003, and started this blog in 2005 (Michael always was more talented and driven than I). I now suspect that writing sermons and writing science fiction stories require a similar kind of imagination: both science fiction and sermons need to be firmly rooted in the here and now, and both need to be connected with infinite possibility.

So there are some things I’ve always dreamed of doing, but have never done; dreams that never quite let go of me, no matter how irrational or impossible.

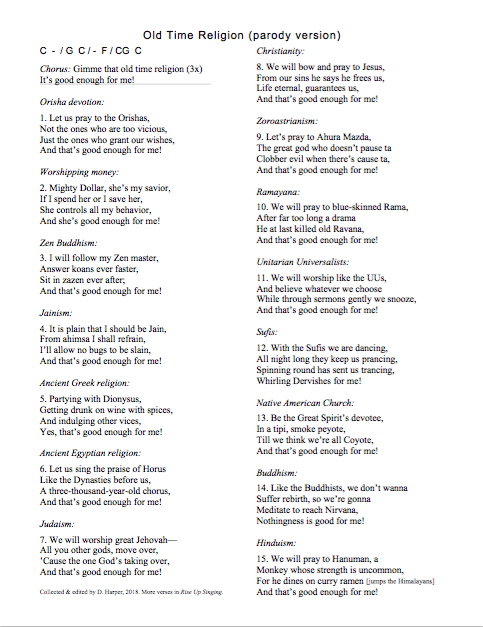

Too much Old Time Religion

29 parody verses of Old Time Religion, plus the traditional last verse (traditional, that is, if you’re a filker). Collected from many different places on the Web (maybe I made a few of them up), edited (both for style and for a vague correspondence to the religion that is parodied), and neatly assembled so that it can be printed (double-sided) on a single sheet of paper. One verse per religion, so you don’t have to sing endless verses based on, e.g., deities from Ancient Greek religions. And guitar chords. I’ll be bringing this to our local song circle, but you’re welcome to print it out and use it for the cat box.

Old Time Religion (parody version), PDF

For Web-based reference, the text of the PDF appears below the fold…

Continue reading “Too much Old Time Religion”