So when you work at a Silicon Valley congregation, you hear Silicon Valley jokes. Like this one:

Q: How can you tell when an engineer is extroverted?

A: When you’re talking with them, they look at your shoes instead of their own.

Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

So when you work at a Silicon Valley congregation, you hear Silicon Valley jokes. Like this one:

Q: How can you tell when an engineer is extroverted?

A: When you’re talking with them, they look at your shoes instead of their own.

The young guy at the oil change shop said with surprise, “How’d you go four thousand miles in less than a month?”

“We drove across the country,” I said.

He looked interested. “How long did it take?”

“Seven days to get across,” I said. “You should do it. It’s an amazing drive.”

He asked me whether I wanted synthetic or conventional oil, and then asked me a few more questions. He wanted to know if we had to bring our passports, and I said no, all you need is your driver’s license. He was fascinated, but seemed a little overwhelmed at the idea of driving all the way across the country. I told him, “You’d love it. Do it before you get old.” He laughed.

Then he and the rest of the crew got to work. Ten minutes later, he came over and handed me the keys. “Remember,” I said, “seven days across and seven days back. That’s your two week vacation. You gotta do it some day.”

He smiled as he turned away. Maybe I’d gotten him thinking about it.

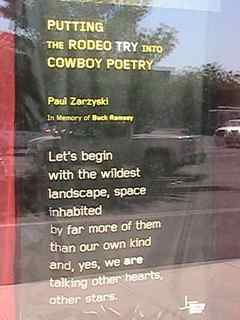

The air in Elko this morning was clean and dry and cool, and it made me feel like a million dollars. We walked a couple of blocks to McAddoo’s in downtown Elko for breakfast, and then headed over to the Western Folklife Center, the home of the Cowboy Poetry Gathering in late January, and currently housing an exhibit on Basque sheepherders that we thought sounded like it was worth seeing. But the Center is closed on Sundays, so we read the cowboy poem that was displayed on six banners hung in six large windows near the entrance. The section of the poem on the first banner read:

PUTTING THE RODEO TRY INTO COWBOY POETRY

Paul Zarzyski

Let’s begin

with the wildest

landscape, space

inhabited

by far more of them

than of our own kind

and, yes, we are

talking other hearts,

other stars…

It was a pretty good poem, and I took photos of each window so I could remember it.

We drove across north Nevada, a land of forbidding desert and mountains interspersed with small green valleys that look so inviting that you want to settle down and live there. We could have lived in Elko, if there were jobs for us; my cousin Susan and her husband ran a computer business in Winnemucca for many years, and I can understand why they wanted to live in a small city in northern Nevada: open and friendly people, bracing desert air, incredible natural beauty that overwhelms even the tawdriest casino. We stopped in Battle Mountain for lunch. It is not as attractive a city as Elko, but it was still a pleasant place to spend an hour or two.

As we made our way down into Reno, the traffic got heavier, and the fact that I would have to return to ordinary life tomorrow at last began to emerge in my consciousness. Then we climbed up out into the Sierra Nevadas, and stopped at the Donner Summit rest area. We needed to stretch our legs, so we walked along some of the trails that connect to the rest area.

One of the trails that connects to the rest area is the Pacific Crest Trail. We met three or four people through-hiking the trail from Mexico to Canada; Carol offered to take photos of Sheepdog, and later of Trivia — these are their trail names, for through-hikers on long distance trails in the United States tend to use trail names rather than their regular names — and then email the photos to them. We chatted a bit with both these hikers, and Sheepdog said that there had been very little water for the last fifteen miles of the trail, and that it had been a very hot day, and that she would have loved a cold can of soda. Unfortunately, we had none to offer her.

We ate dinner at the rest area, enjoying the delightful air that you get in an alpine environment at an altitude of about six thousand feet above sea level. At last it was time to begin the drive back down out of the mountains, down to sea level and the Bay Area. Down, down, down we drove, and when we got to Loomis (population 6,430, elevation 399), I realized that this was probably the lowest altitude we had been at since we left Massachusetts. Down we drove, dodging the crazed drivers going at maniacal speeds — I imagined they were stressed-out people trying to get home after a relaxing weekend in the mountains — and I thought about when we drove under the Appalachian Trail where it crossed Interstate 90 in the Berkshires just a few days ago, and I thought about my friends who hiked the Appalachian Trail, and I wondered where Sheepdog and Trivia would spend the night tonight; and now I sit here at home wondering why we take long trips, pilgrimages, that have no real destination, trips that are taken only for the sake of leaving home and then returning once again.

By noon time, we had almost reached Fort Bridger, Wyoming, and we decided to go there for lunch. We took Business 80 through Lyman (population 2,115, elevation 6,706) and Urie (population 262, elevation 6,785), and thence into Fort Bridger (population 345, elevation 6,673) — three small towns spread along the broad green valley through which winds a narrow river. Jim Bridger, who established Fort Bridger, described the location in a letter from december, 1843: “The fort is in a beautiful location on Black’s Fork of Green River, receiving fine, fresh water from the snow on the Uinta Range. The streams are alive with mountain trout. It passes the fort in several channels, each lined with trees, kept alive by the moisture of the soil.” (quoted in R. S. Ellison, Fort Bridger: A Brief History [Wyoming State Archives, Museums, and Historical Department, 1931, 1981], p. 9)

We pulled in to the Fort Bridger State Historic Site and Museum, and asked the woman who collected our day use fee if there were a restaurant in town. She pointed across the street. We parked the car and walked across to Will-yum’s restaurant for a leisurely lunch — leisurely because neither we nor our waitress nor the owner and chief chef of Will-yum’s were in any great hurry.

The Fort Bridger State Historic Site proved to be very satisfying. It has remained untouched by modern curatorial trends, so there were no interactive displays, no over-researched,painfully-objective descriptive captions. Whoever set up the displays got us to use our imagination so that several different eras were brought to life: the original fort and trading post for the emigrant trains in the 1840s, the brief life of the Pony Express in 1860-1861, the U.S. military post in the 1880s, the tourist trade along the Lincoln Highway in the 1930s. I think my favorite part was the Black and Orange Cabins, a motel built in 1929, which is mostly restored. Kelvin Hoover, a costumed guide, showed us around. You can look in the windows of the cabins and see what it might have been like had you stayed in one in the 1930s: the tiny little wood stove with a kettle on it, the simple wood shelves, an old-fashioned Edison light bulb hanging from the ceiling. Each cabin had its own open garage, and there was a small power plant to generate electricity for the lights, but you had to walk down to the end of the cabins to use the outhouse.

Kelvin Hoover in front of Cabin no. 1 (photo credit: Carol Steinfeld)

As we drove west through Wyoming, we saw fewer cattle. We saw a few oil derricks, and mysterious industrial plants out in the middle of nowhere, and what appeared to be mines, and lots of wind turbines. I picked up a copy of the Wednesday, July 17, number of the weekly newspaper Green River Star, and found three articles by editor David Martin on wind farms; obviously wind farms are of growing importance in southwestern Wyoming. Martin reports that “Carbon County has nine wind farms comprising a total of 492 turbines,” and county commissioners in Sweetwater, Carbon, and Uinta counties continue to wrestle with how to regulate development of wind farms. The western landscape is not an empty wilderness, it is being heavily used by us humans for the extraction and exploitation of raw materials and energy.

In the late afternoon, we had gotten past Salt Lake City, and on a whim we pulled off the highway to see the Great Salt Lake. We pulled into the parking lot of Great Salt Lake Park and Saltair Beach. The water was a good distance from the parking lot, and we could see people walking out across the sand and mud towards the water. We started walking. The footing was mostly solid sand, but in places we had to walk through slippery sloppy mud a few inches deep; Carol was wearing flip-flops and she wailed that the mud was hot. The sun was hot, too, and the hot wind carried a distinctive odor, sort of like low tide. There were what appeared to be ice crystals in the mud at one point; but the crystals were salt, not ice.

When we were out near the water, I looked back at the Kennecott copper smelting plant and its huge smoke stack, over 1,000 feet tall. In the west, the stark beauty of the landscape is usually paired with some kind of crazy-ass human-built structure, often huge or sprawling, that’s so ugly it becomes stunningly beautiful:

By the time we got to the Wyoming border, Carol said she was ready to leave Nebraska. I didn’t say so, but I enjoyed the drive through Nebraska. Near Kearney, I liked the way the highway followed the broad flat valley of the Platte River, every so often crossing over one channel of the river or another, passing between green fields of corn and hay fields and lines of trees along the river channels and the very occasional small city. As we got further west, we saw fewer and fewer trees, and more cattle, and here and there a field of golden wheat. The land gradually rose up and up until we were in the high plains, and most of the land was range land. Now and again we passed cattle, mostly clustered around stock ponds in the heat of the day, and I thought about the story that I had read in yesterday’s issue of the Kearney Hub — “125th year, 230th issue”; “At the center of Nebraska life since 1888” — that told how the U.S. Farm Service is going to allow “emergency grazing on about 900,000 acres in Nebraska because of the ongoing lack of forage for livestock”; Western Nebraska is one of the regions where emergency grazing will be allowed, for conditions continue to be drier than normal, even though “conditions appeared to improve at the beginning of the year.”

Once we got into Wyoming, the scenery did get more dramatic. Not long after we passed over the border, we saw sagebrush growing by the side of the highway, and not long after that we saw our first oil derrick bobbing slowly up and down, and then we caught our first sight of tall mountains in the blue distance. We drove past strange rock formations, and watched the railroad wind its way around the sides of hills and buttes. The railroad reminded me of something we saw yesterday: As we drove out of Yankton, South Dakota, before we crossed over the Missouri River on U.S. Route 81, we had to stop at a railroad crossing for two Union Pacific trains to go by; the train headed west consisted of a long line of empty hopper cars, and the train headed east consisted of a long line of hopper cars filled with coal; I suspected that the coal came from the huge Powder River Basin mines on federal lands in Wyoming, since something like eighty train loads of coal come out of Powder River Basin each day.

We stopped in Laramie to visit the food coop there, and stock up on good food. We happened to arrive just when the farmer’s market was taking place, so we wandered around, talking to people in the various booths. Carol got a small bag of summer apples, and some spinach. I got some raw honey and a loaf of olive bread. Carol got some raspberry leaf tea, and an inexpensive necklace made out of a seashell by the nice young man who sold it to her. I found Second Story Books in the next block, browsed for a while, and came away with a biography of Hans-Georg Gadamer, and a book published by the University of Nebraska Press written by a man who had traveled all over the Great Plains for several months, stopping in small towns and talking with whoever came his way. We finally made it to Big Hollow Coop. The man who took our money was from Jackson, California, and had come to Laramie because his girlfriend was in graduate school there. He told us that Big Hollow is the only coop in the whole state, which surprised me; I expected that there would at least be one in Cheyenne.

We stopped to eat our dinner at a highway rest area outside Laramie. It was very windy, but the picnic table had brick walls surrounding three sides, and a wooden roof, so we could shelter from the wind. A pair of Barn Swallows was also taking shelter in the picnic, and they had built their nest up in the rafters; I could just see one swallow’s tail projecting out a little beyond the mud walls of the nest.

We stopped just before sunset at a parking area just before the exit for Creston Junction, Wyoming, and got out to stretch our cramped legs. We looked out over the sagebrush tinged gold by the setting sun, the mountains in the distance now turning pink and purple, the picturesque white clouds — and I realized something out in the sagebrush was looking at me. “See that?” I said to Carol. “An antelope.” She spotted two more. One of them looked at us, saw that we were too far away to be a threat, grazed on some sagebrush, and began moving west; the other two were also moving west, heading towards the setting sun.

After we ate breakfast, Carol and her aunt wanted to spend the morning talking about family. I went for a walk along the Auld-Brokaw bike path in Yankton. It was pleasant enough when you could feel the wind, but when I got to the Yankton high school, the path was in the lee of a hill, and there was no breeze at all, and it was quite hot. I was glad to get back to Carol’s aunt’s tree-shaded house. But she and her aunt were deep in family recollections, and I decided to visit the National Music Museum, which was just a few miles away.

The National Music Museum is housed on the campus of the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. I found a shady parking place down the street, and walked in. The pleasant woman at the front desk told me there was an audio tour available, but I said I only had an hour, and pretty much knew what I wanted to see. It took me a few minutes — I kept getting distracted by all the amazing and beautiful instruments on display — but pretty soon I found the mountain dulcimer made by J. E. Thomas in Kentucky in 1912. I had seen the instrument on their online checklist, and was pretty sure they would display an instrument by the traditional builder who had perhaps the greatest influence on the revival of the mountain dulcimer. Their instrument has some damage — it has a small crack in the soundboard, and one of the sides has separated from the soundboard at the lower bout — but it is still a good example of how Thomas made his instruments. I paid particular attention to the flat grain of the soundboard; the way the outer strings bore against the sides of the pegbox; the frets made of wire staples; the wooden nut and bridge. While well-made, this is a folk instrument, not a finely-crafted product of a luthier’s shop.

I also noticed a square piano made by John Osborne of Boston about 1824. I noticed this instrument because it had come from the Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts, as a transfer in 2012. The Rotch-Jones-Duff House had been refining its collection while I lived in New Bedford, and presumably the curators either decided that this piano had no real connection to the house, or that they couldn’t adequately care for it. In any case, it has found a lovely home, and it now stands back to back with another square piano from a different Boston piano maker of the early nineteenth century, allowing people to compare subtle details of the cabinetry between two similar instruments.

I tore myself away from the National Music Museum. I could have spent several more hours there, looking at all kinds of instruments: novelty ukuleles; an original theremin; tools, molds, jigs, and benches from a guitar maker’s shop; the same from a luthier’s shop; clavichords; serpents; an epinette des Vosges; a trumpet marine; an 1850s Martin guitar; etc. On my way out, I talked briefly with the woman at the front desk, and she said the museum hosts weekly concerts when school is in session, occasionally using instruments, particularly keyboard instruments, from the collections. For a certain kind of person, it would be worth a special trip to Vermillion, South Dakota, to go to the museum and attend one of those concerts.

We left Carol’s aunt’s house in the middle of the day, had a quick lunch in Yankton, and began driving due south on U.S. Route 81 towards Interstate 80. We crossed the river into Nebraska, and the road climbed up out of the flat river basin into rolling plains. Along with the fields of corn and soybeans we have been seeing ever since Ohio, we started seeing fields with cattle, fields of hay being cut, and other fields of hay already cut and now being baled. The two-lane highway rolled through the green fields, a few trees lining the creek beds or surrounding isolated farm houses, the giant irrigation structures spraying water. We stopped in Norfolk for gas, and bought the local newspaper, the Norfolk Daily News; the front page stories included the following lead paragraphs: “Nebraska has a new tool for fighting wildfires — a single engine air tanker that arrived in Valentine earlier this week.” — and — “An Omaha trial lawyer is making his way through the state, announcing his candidacy for U.S. Senate.”

We stopped in Grand Island, Nebraska, not long before we got back on the interstate. Carol went to buy some fruit juice at the Azteca Market, and I went across the street to The Tattered Page, a used book store. As I was looking through the books, I heard some guys talking about experience points and hit points, and later I saw books for gamers. I walked up to the cashier to buy a copy of Bret Harte’s stories — a former library book that was indeed somewhat tattered — and said to the cashier, “I like the combination of used books and role playing games.” He smiled, and another guy sitting nearby said, without looking up, “Give the people what they want!”

On the interstate, I saw what looked like a bus in front of us. It was a bus, and the lighted destination sign in back read “SF.” The color scheme of the bus looked familiar. As we passed it, we saw that it carried a familiar logo reading MUNI, and other signage proclaimed that it was a hybrid electric vehicle that used biofuels. “Look at that bus!” I said to Carol. We laughed out loud to see a San Francisco bus on the highway in the middle of Nebraska. Later, when we got to our motel in Kearney, we discovered to our delight that the bus was spending the night here as well:

Once we left Joliet, it wasn’t far to the outer edge of Chicagoland, that vast sprawling patchwork of suburbia and small cities that extends outward an hour’s drive from Chicago itself. And once we got past Joliet, it felt like we left behind the hustle and bustle and density of the eastern third of the United States: traffic got lighter, the distance between cities became greater, it seemed as though I could feel the density of human beings grow less.

We crossed the Fox River. We used to live near the banks of the Fox River, quite a ways upstream from where we crossed it, ten blocks from the little 1842 stone church building, built of stone hauled up from the river bed in part by the minister, Augustus Conant, the second oldest Unitarian church building still standing west of the Alleghenies.

The miles rolled by. We drove through the barely rolling fields of central Illinois, past the Quad Cities, into the gently rolling land of Iowa, driving almost due west. As we drove, I thought about the dream I had had last night:

Have you climbed up the tower? All the way to the top six levels? someone said to me.

No.

They implied the climb would be spiritually rewarding. So I started to climb.

The first six levels I had already gone up and down: prosaic open-mesh iron staircases of the kind you find in old industrial plants, winding up through a rusted iron structure. Then the staircase from the sixth to the seventh level got very steep, and was behind an iron gate that creaked open.

Then I got into the seventh level. This was the children’s level. A woman I had known in high school sat talking with some children. Bright walls, interesting toys. I moved some mannequins or puppets or dolls made out of wire, to get at the moveable stair case that would get me to the next level.

The eighth level was the map level: it was a balcony around the children’s level, with maps in big wide chart drawers, with big windows above the drawers to look out at the sun setting over the city and landscape beyond….

It was at this point in the dream that the horrendously loud fire alarm went off in the motel. We stumbled around, preparing to get out of the building, when the alarm went silent. We went back to bed, and I began to dream again:

…The ninth level was reached by a steep staircase, the level of Eternal Night: galaxies, suns, darkness, whirling around, and it appeared that in the darkness two or three awe-struck people sat, but of that I couldn’t be sure. I did not stay long there, because it seemed to me that it would be easy to stay there forever.

The tenth level was the level of peace, a peace that surpassed understanding, a place to be in peace. One man sat zazen — I looked at him, and thought, a little scornfully, how stereotypical! — this was a place where peace permeated your being without some painful exercise. I did not stay long here, either.

The eleventh level was the library: low bookshelves all around the four walls, under big picture windows with the sun shining in, trees and birds singing. I wanted to spend a long time here.

The twelfth level: a woman on the stairs warned me that the air was thin. I climbed up the next few stairs. The air was indeed thin; ten thousand, maybe fourteen thousand feet above sea level. I had a hard time catching my breath, but it was a stunning view.

Thinking about such trivial things can occupy the mind for many hours while driving. If you chose, I suppose you could interpret this dream as having deep metaphorical meaning; I ignored any supposed meaning, and just enjoyed remembering it. Soon we stopped at the self-proclaimed largest truck stop in the world. While Carol was inside getting something to drink, I watched as truck pulling an incredibly long blade of a wind turbine held up traffic as it slowly maneuvered into the truck stop:

At the western edge of the loess hills of western Iowa, we pulled off at a sign that said “Scenic Viewpoint.” The entrance road wound up a knoll. We parked at the top, and climbed up half a dozen flights of steps made of pressure-treated two-by-twelves supported by telephone poles. At the top, we gazed around us: the broad valley of the Missouri River to the west, and to the north, east, and south, the loess hills rising two or even three hundred feet above the bottom of the valley. The tower swayed slightly in stronger gusts of wind, making me feel a little seasick. We were in a hurry to get to Yankton, to we climbed down and began driving again.

Heading north on Interstate 29, we drove through that broad valley of the Missouri River; through the strong smells of the rendering plants near Sioux City, winding along as we roughly paralleled the invisible river somewhere off to our left. After a time we left the interstate and headed due west, slowing down as we drove through the little college town of Vermilion, South Dakota, speeding up again on the other side until we reached Yankton. We ate dinner with Carol’s aunt, and I got to see pictures of Carol as a baby and a little girl.

After breakfast served on the front porch of the White Inn in the village of Freedonia, we got back on Interstate 90 and started driving west. We drove through the hills of western New York state and northwestern Pennsylvania and the Western Reserve of Ohio, the waters of Lake Erie (elevation 570 feet above sea level) invisible somewhere off to our right.

After we got through the sprawl of Cleveland, the land flattened out, and we felt that we were in the true Midwest: a less dramatic landscape than the northeast, one that is best appreciated when seen from close at hand. For when the Midwest is seen close at hand, you can see the details that make it charming: creeks and small rivers at the bottom of gullies and ravines, hedgerows and small patches of woodlands nestling in among fields of corn and soybeans, hundred year old farmhouses turned into residences while the surrounding fields have been bought up by agribusiness, old barns falling into quaint and attractive disrepair. Even the industrial buildings that punctuate the landscape, and the high tension lines that tie industry together, and the mile-long freight trains loaded with containers being shipped across the continent look almost attractive, if not quaint, under the gentle clouds and high-arching blue sky.

Carol had some business that she had to take care of during business hours today, so we stopped at two or three different rest areas in Ohio and Indiana so she could use the free wifi connections. I started eating some blueberries at one rest area in Ohio, and thought about how I had picked those blueberries in Massachusetts two days ago with my friend Will, on the farm where four or five generations of his family have lived. We walked along the neatly mowed paths between the blueberry bushes, which grew six to nine feet high, the branches thick with berries, mostly green berries, but plenty of ripe ones for us to pick, and either put in the plastic containers that hung around our necks or pop in our mouths. We picked two gallons of berries while we caught up with each other’s lives: health problems with our siblings, what his children are doing, how our parents are doing, etc.

Before we started picking, I told Will and his wife about the invasive Asian fly that moved into southern New England last year and decimated the blueberry crops for many growers in New Hampshire. I told them how the flies lay their eggs in the berries, and when the farmers get the berries to market, sometimes they find maggots crawling out of the berries; not an appetizing sight for potential buyers. Their eyes got big — it’s not often that you actually see someone’s eyes get big, but theirs did — as they heard about such a devastating pest. Blueberries have been an easy crop to grow in New England, since they evolved here; as opposed to apple trees, which evolved elsewhere, are troubled by native New England pests, and require lots of care.

I had heard about these invasive flies just a couple of days earlier, on Firday, when Carol and I went up to Apple Annie’s orchard in Brentwood, New Hampshire, so that Carol could look at a composting toilet that was malfunctioning. Carol was fascinated because it was a composting toilet that she had never seen before. I was fascinated to hear Laurie tell about the invasive flies, which she had learned about in a course she took to re-certify for her pesticide certification. She said they prefer red fruits, so rasberries are even more vulnerable — raspberries, which used to be yet another relatively pest-free crop in New England.

So I ate my New England blueberries in a rest area in Ohio, thinking that this might be the last easy crop of blueberries grown in my home town. Who knows why that Asian fly finally chose last year to arrive in New England. There are too many human beings everywhere, prying into niches in ecosystems where they don’t belong, moving species from one ecosystem to another at an alarming rate, and warming up the planet so that certain invasive species suddenly have to potential to disrupt native species. I would not be upset if nine-tenths of all humans died off suddenly, and I’m willing to be one of them — but I’m only willing to be one of them if we really get rid of nine-tenths of human beings; although I guess I could settle for a seven-eighths mortality rate.

We stopped again at a rest area in Indiana, where Carol and I took a long walk out through the employees’ parking lot and down a country road. On our right hand side was a corn field. It was not a field of sweet corn, grown to be sold at roadside stands and eaten as corn-on-the-cob. Carol recalled how we had once had a housemate who talked about “cow corn,” tough corn sold for cattle fodder. I said that there was a good chance this wasn’t even cow corn, but rather industrial corn bred to serve as the raw materials for chemical processes that produce ethanol, high-fructose corn syrup, corn oil, corn steep liquor, polylactic acid used to make corn-based plastics, and other industrial products.

On our left hand side was a patch of woodlands, covering at least twenty acres, that made the air feel twenty degrees cooler. We noticed black splotches on the road, and realized that mulberry trees hung over us. We picked as many ripe mulberries as we could reach reach, and ate them, the sweet elder-y taste a perfect complement to a hot humid afternoon.

We left the house of Carol’s dad and his wife at about half past nine this morning, and started driving west. We drove down Interstate 495 to 290 to 90, through the hills of central Massachusetts. I lived most of my life in relatively flat eastern Massachusetts, where small hills rarely rise more than a couple of hundred feet above the general level of the land, where the rivers may take several miles to drop a few feet, where eskers rise up out of swamps. Stow is a few miles to the west of where I grew up, on the edge of the central Massachusetts hills. This part of Massachusetts was settled in the mid-eighteenth century, reached a peak in population half a century later, and in some areas is still less populous than it was in the nineteenth century. The soil is relatively poor and as soon as the rich land west of the Hudson River opened up, people began to leave central Massachusetts. When I did some supply preaching in north central Massachusetts a decade ago, it was hard to find a full-time job, and the great hope of economic salvation was that the commuter rail would extend out far enough that people could commute to the great economic engine that is Boston; the commuter rail never got extended, and I have little doubt that the Great Recession made things worse, not better.

Nevertheless, the tree-covered rolling hills, dotted with crooked roads and clapboard houses, are beautiful; a subtle beauty equal to the dramatic beauty of the California coast. On a hot summer day like today, I think the central Massachusetts hills are more beautiful: the moist air makes distant hills look blue, giving a delightful sense of distance; and the wet spring has made all the vegetation incredibly green.

We climbed up through the Berkshires, reaching an elevation of 1,724 feet; we will not reach that elevation again until we get to Hamilton County, Nebraska. Hamilton County, with a total area of 547 square miles, has a total population of fewer than 10,000 people; Berkshire County, with an area of 947 square miles, has a total year-round population of over 130,000, and a summer population higher than that.

As we drive through New York state, I read aloud to Carol from the newspaper coverage of the aftermath of the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin. Neither of us was surprised that Zimmerman was acquitted. Carol wondered how the prosecutors allowed a jury to be seated that had no black people; I wondered how Florida could be so stupid as to have a law on the books that basically legalizes murder. I read aloud a quote in the newspaper story that captured something else I was thinking: if Zimmerman had been black and Martin had been white, odds are pretty good that the outcome of the trial could have been different.

After a boring, uneventful drive, we arrived in Fredonia, New York, at about half past six. It was still hot and humid, but we immediately went for a walk so we could stretch our legs. A block or two from our hotel, we came to small cemetery. A plaque facing the street read:

“The Pioneer Cemetery, Town of Pomfret. This site was given by Hezekiah Barker for a cemetery and the first burial here was in 1807. There are 15 known Revolutionary soldiers and many other earlier settlers of Pomfret resting here in this pioneer cemetery. This marker placed by the Pomfret Town Board — 1977. Elizabeth L. Crocker — Town Historian.”

I would not be surprised if at least some of the people buried in this cemetery were originally form the central hills of Massachusetts. I could not find any of the older grave stones that were still legible, though there were a number of old slate stones that were broken or shattered by frost and moisture. Most of the stones that were legible were less interesting mid- to late nineteenth century stones. But I did find one attractive stone, obviously hand-lettered, lying flat on the ground where it had fallen long ago:

The inscription, as near as I could make it out, reads: “In memory / Lucyett Smith / Who Died July 16th, 1846 / Age 19 years 3 Months & 1 day.”

Saco, Maine — I’m at Religious Education Week at Ferry Beach, the Universalist conference center in Maine, taking a class in religious education. One of the people in my class had a big church wedding down in Texas several months ago, which wasn’t a legal wedding because she and her wife are both women. With the recent Supreme Court decision against the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DoMA), their advisors told them that they should have another wedding in a state which sanctions same-sex marriage; Maine, of course, is one of those states. So right after class was over, we all walked over from where we were meeting to the chapel in the grove, and there, under the pine trees still dripping with rain from a passing shower, they were legally married in a brief but meaningful ceremony.

Our teacher and one of our classmates were the witnesses who signed the wedding documents. They fed us cake and champagne after the ceremony.

It is worth stating the obvious: one effect of the recent Supreme Court decision is (and will be) marriages like this one; even if a same-sex couple can’t be legally married in the state in which they reside, by getting legally married in a state which recognizes same-sex weddings, they can still access some federal marriage benefits. (And I’m thinking that if I’m asked, I would perform such brief ceremonies for out-of-state same-sex couples at no charge.)