Sermon copyright (c) 2023 Dan Harper. Delivered to First Parish in Cohasset. The sermon text may contain typographical errors. The sermon as preached included a significant amount of improvisation.

Readings

The first reading is from The Abuse of Evil: The Corruption of Politics and Religion Since 9/11, by Richard J. Bernstein:

“This new fashionable popularity of the discourse of good and evil … represents an abuse of evil — a dangerous abuse. It is an abuse because, instead of inviting us to question and to think, this talk of evil is being used to stifle thinking. This is extremely dangerous in a complex and precarious world. The new discourse of good and evil lacks nuance, subtlety, and judicious discrimination. In the so-called ‘War on Terror,’ nuance and subtlety are (mis)taken as signs of wavering, weakness, and indecision. But if we think that politics requires judgment, artful diplomacy, and judicious discrimination, then this talk about absolute evil is profoundly anti-political. As Hannah Arendt noted, ‘The absolute … spells doom to everyone when it is introduced into the political realm.’”

The second reading is from A Pocketful of Rye, a murder mystery by Agatha Christie. In this passage, Miss Marple and a police inspector are discussing who might have committed a murder:

“[Inspector Neele] said, ‘Oh, there are other possibilities, other people who had a perfectly good motive.’

“‘Mr. Dubois, of course,’ said Mis Marple sharply. ‘And that young Mr. Wright. I do so agree with you, Inspector. Wherever there is a question of gain, one has to be very suspicious. The great thing to avoid is having in any way a trustful mind.’

“In spite of himself, Neele smiled. ‘Always think the worst, eh?’ he asked. It seemed a curious doctrine to be proceeding from this charming and fragile-looking old lady.

“‘Oh yes,’ said Miss Marple fervently. ‘I always believe the worst. What is so sad is that one is usually justified in doing so.’”

Sermon: “Evil in Our Time”

I’ve noticed something recently. In our society today, we like to talk about evil in the abstract. We like to say that racism and sexism and homophobia are evil. We like to say that the other political party is evil — or that all politics is evil. We say that violence is evil. We like talking about evil in the abstract.

But we’re less willing to talk about the specifics of evil. When we do talk about the specifics of evil, we choose a few small examples of a greater evil, and focus on that. So when we talk about the looming global ecological disaster, we talk about how people need to drive electric cars, but we don’t talk about how first world countries like the United States need to make major policy changes regarding both corporate and private energy use. Nor are we likely to talk about the other large major threats to earth’s life supporting systems, including toxication, the spread of invasive species, and land use change.

I understand why we tend to focus on a few small examples of evil, rather than seeing the big picture; I understand why we see the trees but not the forest. When we reduce evil to abstractions, or to small specific actions, we don’t have to give serious consideration to the political and social change necessary to put an end to racism. It’s a way of keeping evil from feeling overwhelming.

But when we reduce evil to an abstraction, we cause at least two problems. First, reducing evil to an abstraction tends to stop us from thinking any further about that evil. Second, by reducing evil to an abstraction, we ignore the individuality of human beings; to use the words of philosopher Richard J. Bernstein, we “transform [human beings] into creatures that are less than fully human.” We stop thinking, and we stop seeing individuals. I’ll give an example of what I mean.

Prior to coming here to First Parish, a significant part of my career was spent serving congregations that needed help cleaning up after sexual misconduct by a minister or other staff person. (Just so you know, I’ve served in ten different congregations, many of which were entirely healthy. Although I’m going to give you an example based on sexual misconduct by a minister, I’ve changed details and fictionalized the story so innocent people can remain totally anonymous.)

Once upon a time, there was a minister who had engaged in inappropriate behavior with someone who was barely 18 years old. I was hired to clean up the resultant mess. Because I’ve done a fair amount of work with teens, I was ready to demonize this particular minister, thinking to myself, “Legally this minister may be in the clear, but morally I’m going to call this person evil.” Because I thought of this minister as evil, I assumed anything they did was bad.

But then I found out that this minister had helped someone else in the congregation escape from a domestic violence situation. This required extended effort on the part of that minister, extending over a period of several years. This minister whom I had thought of as evil helped the domestic violence survivor to get out of the abusive relationships, find safe housing, extricate the children from the control of the abusive spouse, and settle down to a new life of safety. I was very suspicious of this story — surely this evil minister must have done something inappropriate with the person whom they had helped, or engaged in some other evil act. But it slowly became clear that in this case, the minister had done nothing wrong, and by extricating that person from domestic violence, that minister’s actions were wholly good.

This little story was a useful reminder to me: individual human beings are neither wholly good nor wholly bad. A person whom I had considered wholly evil was not, in fact, wholly evil; was, in fact, capable of amazing goodness. I had been in the wrong: when I called that person evil, I stopped myself from seeing the good they had done; I transformed that person into someone who was less than fully human. Mind you, I still kept my distance from that minister, feeling it was safer to do so, but at last I could see them as more than a caricature, I could see them as a complex individual.

We human beings are complex creatures. I would venture to say that no one is wholly evil — no, not even that politician that you’re thinking about right now. Even that politician whom you love to hate has redeeming qualities, though you may not be able to see them. We must always keep an open mind, and assume that every human being has the potential of doing good.

By the same token, I’d have to say that no one is wholly good. This is point the fictional character Miss Marple makes in the second reading this morning. Even someone who is essentially good can carry out evil actions. I don’t quite agree with Miss Marple when she says, “I always believe the worst. What is so sad is that one is usually justified in doing so.” Unlike Miss Marple, I don’t go around always believing the worst of everyone. But I do live my life in the awareness that everyone is capable both of evil and of goodness. Every human being has the potential of doing evil, but also of doing good.

If every human being is capable both of evil and capable of good, then you can see why we should not brand someone as wholly evil, or as wholly good for that matter. When we brand someone as wholly evil, that stops us from thinking about the evil that they caused. In that example of the minister that I just gave, when I branded that minister as wholly evil, I stopped thinking. When I started seeing them as a human being who was capable of both good and evil, I began to think more clearly, and I realized that there were external factors that led them into misconduct — external factors that were still at play, and that could lead to someone else engaging in misconduct. As I began to think more clearly, I was able to work with others to make that kind of behavior less likely in the future. It was only when I started thinking again that I was able to begin to work with others to try to prevent evil from happening again.

From a pragmatic standpoint, then, it’s foolish to brand someone as wholly evil; but it’s also morally wrong to brand someone as wholly evil. When we do that, we remove their individuality; we turn them into something less than human. We deny their individuality and deny their freedom, their capacity to make free choices in the way they act. The philosopher Richard J. Bernstein points out that this is the way totalitarianism works: he writes, “totalitarianism seeks to make all human beings superfluous — perpetrators and victims.” When we brand other people as evil, we are doing exactly what totalitarian regimes do: branding opponents as evil, denying human individuality, stopping everyone from thinking. Totalitarianism thrives when people stop thinking.

It is this tendency that troubles me about politics in the United States today. We brand our political opponents as being evil. Democrats say that Donald Trump is evil, and Kevin McCarthy is evil, and Marjorie Taylor Green is evil. Republicans say that Joe Biden is evil, and Nancy Pelosi is evil, and Barack Obama is evil. Even those who are independents — and here in Massachusetts, more people register as independent than either Republican or Democrat — even political independents play this game when they say all politicians are corrupt.

This kind of thing stops people from thinking. When Democrats brand Donald Trump as wholly evil, not only are they denying his essential humanity, but they have started walking down the road to totalitarianism. When Republicans say that Nancy Pelosi is evil, they are denying her essential humanity, and they too are starting to walk the road towards totalitarianism. When political independents claim that all politicians are corrupt, they are denying the essential humanity of all politicians, and — you guessed it — they have started walking the road towards totalitarianism.

Evil exists, but totalitarianism is not the solution for evil. Totalitarianism means that one person, or a small group of people, make all the decisions. But that one person, or that small group of people, can easily slip into doing evil themselves — and there will be no one to hold them accountable, to tell them to stop. This is what is happening in Russia right now: Russia has become a totalitarian state, so when Vladimir Putin decided to do evil by invading Ukraine, there was no one to stop him.

We can only stop evil through communal action, through cooperating with as many people as possible. This is the principle behind democracy: by cooperating widely, we minimize the chance of totalitarianism. But it’s hard to cooperate with other people when you brand half of the population as evil — as happens when Democrats brand Republicans as evil, and Republicans brand Democrats as evil, and Independents brand everyone else as evil, or at least corrupt. Calling other people evil is not serving us well. We don’t want to sound like Vladimir Putin.

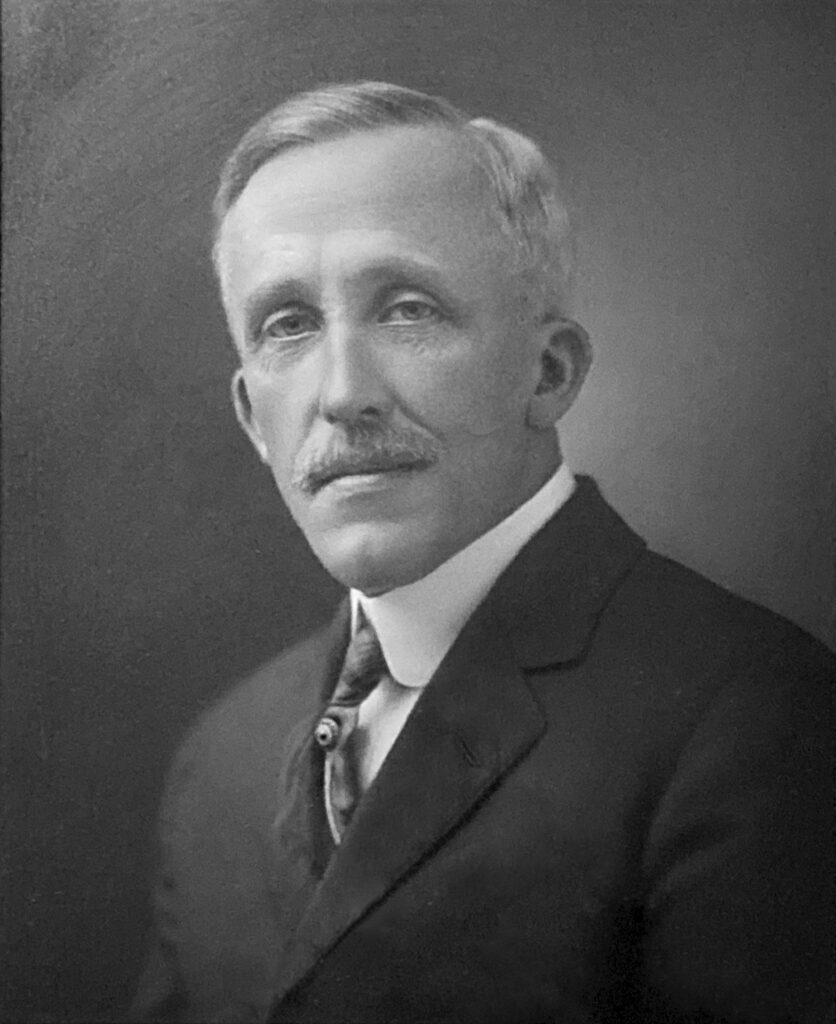

There’s actually a religious point buried in all of this: Every single person has something of value in them. That something of value might be buried pretty deep, but it’s there. That’s what the Unitarian Universalist principles mean when they talk about the “inherent worth and dignity of every person.” That’s what the Universalist minister and theologian Albert Zeigler meant when he said, “every person and what they do and how they do it is of ultimate concern, of infinite significance.” When you brand a person as evil, you deny their inherent worth and dignity, you say that person somehow lacks infinite significance. We can say that a person has done something evil; we can say that we no longer trust that person, and that we don’t want to have anything to do with them if we can help it. But that does not mean the person is evil; some of their actions were evil, yes; but the person is not evil.

There’s another religious point that goes along with this. When we recognize that each and every person is of infinite significance, we make a statement of great hope. Each person, each individual, has within them an infinite capacity for goodness; they may also have a capacity for evil, but evil is finite and good is infinite, so their capacity for evil can be overpowered by their capacity for goodness. Every person, even someone who has done something evil, can be redeemed. Remember the fictional minister I told you about: that minister did something horribly evil, but they also had within them the capacity for amazing goodness.

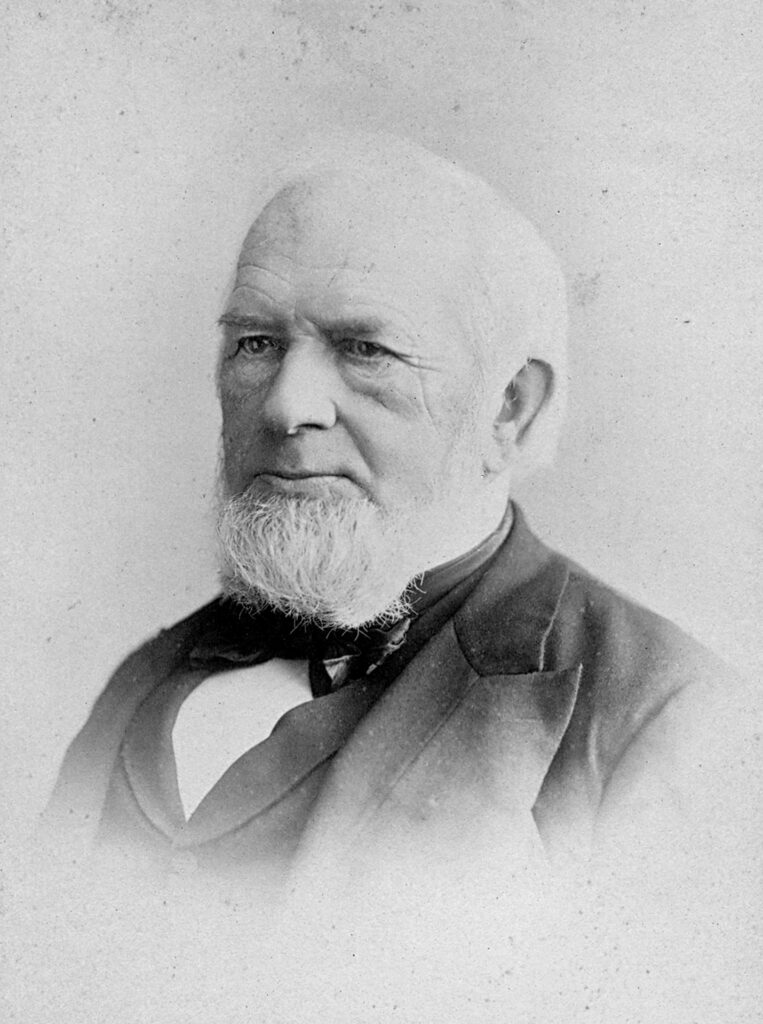

In the end, the collective human capacity for goodness will win out over the collective human capacity for evil. This is what Martin Luther King Jr. meant when he said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Dr. King was actually paraphrasing a sermon from the great Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, who said: “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe. The arc is a long one. My eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by experience of sight. I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see, I am sure it bends toward justice.” So said Theodore Parker a century and a half ago.

Today, we still have a long way to go before we overcome evil. I’m pretty sure we won’t overcome evil in my lifetime. I doubt we will overcome evil in the lifetime of anyone alive today. But I’m sure that the universe bends towards justice. Like Moses leading the ancient Israelites, or like Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement, we know the Promised Land is somewhere ahead of us; we hope to catch a glimpse of it before we die; but we will not reach it ourselves. Yet we continue to strive towards justice.

We continue to hope. We continue to see the good in others whenever we can: so that we may cooperate as much as we are able; so that one day, justice may one day roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.