Sermon copyright (c) 2025 Dan Harper. As delivered to First Parish in Cohasset. The sermon as delivered contained substantial improvisation. The text below has typographical errors, missing words, etc.

Readings

The first reading was the poem “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes.

The second reading was from the essay “The Need of an Industrial Education in an Industrial Democracy” by John Dewey:

“It is no accident that all democracies have put a high estimate upon education; that schooling has been their first care and enduring charge. Only through education can equality of opportunity be anything more than a phrase. Accidental inequalities of birth, wealth, and learning are always tending to restrict the opportunities of some as compared with those of others. Only free and continued education can counteract those forces which are always at work to restore, in however changed a form, feudal oligarchy. Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.” [John Dewey, Manual Training and Vocational Education (1916)]

Sermon: “Religion and Public Education”

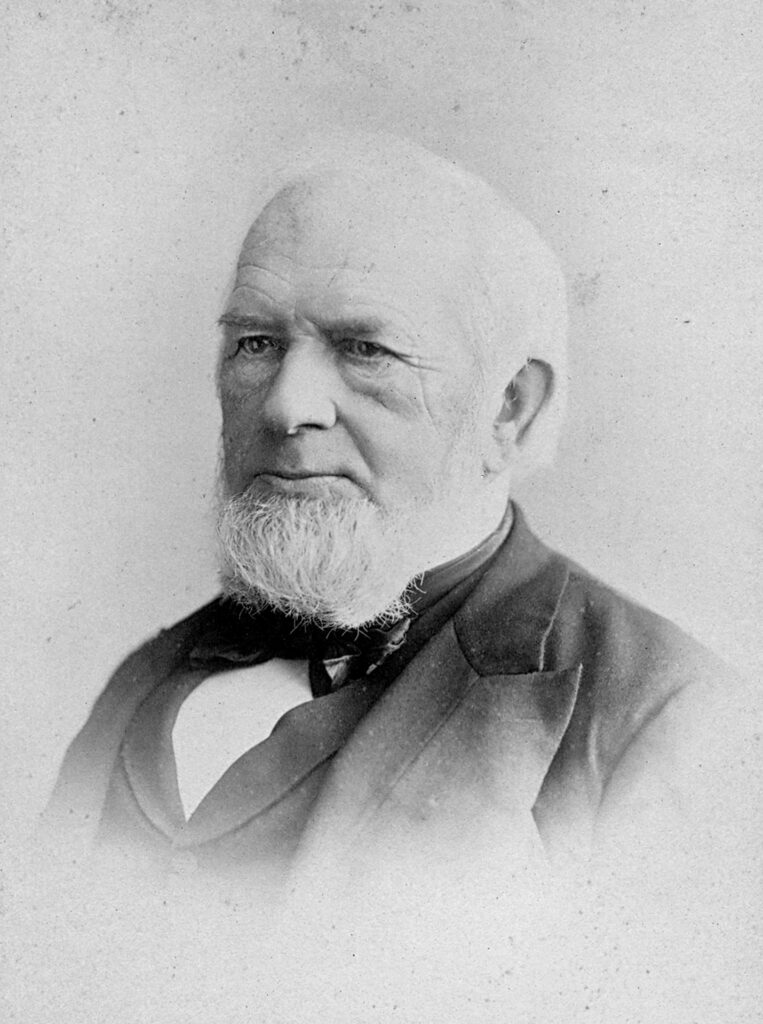

Unitarian Universalism has a long history of being concerned with public education. This begins at least as far back as the work of Horace Mann, a Unitarian who served as Secretary of Education in Massachusetts in the mid-nineteenth century, and did more than anyone to establish the idea of universal, free, non-sectarian public schools as the norm in the United States. Our own congregation was also deeply involved in public education in the mid-nineteenth century; we allowed our then-minister, Joseph Osgood, to serve as the superintendent of the town’s schools while he was serving as minister. Osgood worked tirelessly at the local level for the same goal of universal, free, non-sectarian schools.

The involvement of Unitarians, and to a lesser extent Universalists, in public education continued through the late twentieth century. Many Unitarians became teachers; many Unitarians served on their local school boards; and Unitarians also advocated tirelessly for universal, free, non-sectarian public education at the national and state levels. Our reasons for doing so are fairly straightforward. We Unitarian Universalists believe that public schools are essential for a strong democracy; and we believe in democracy as the governmental system best designed to help us establish a society oriented towards truth and goodness. We are well aware that both democracy and public education are imperfect vehicles for helping to establish a society devoted to truth and goodness. Both democracy and public education can be diverted away from truth and goodness, towards lesser goals like personal gain and power politics. But, to paraphrase the old saying, so far they’re better than any other system anyone has come up with. And public education is essential to democracy because an informed electorate is essential to democracy.

Besides, we Unitarian Universalists are idealists, in the sense that we believe in the perfectibility of humanity. As the Unitarian minister Theodore Parker said, and as Martin Luther King, Jr., later paraphrased, the moral arc of the universe may be long, but it bends towards justice. Thus the reasons why we Unitarian Universalists support public education are fairly straightforward. I’d like to review with you some of our past support for public education, and then I’d like to talk about why we should recommit ourselves to public education.

And by looking back at education in Cohasset, we can see how far we’ve come. Prior to about 1830, those who wanted their children to have more than basic literacy had to pay for their children’s schooling. Younger children paid to attend “dame schools,” often taught by a widow who needed income. For young teens who wanted the equivalent of a high school education, Jacob Flint, minister at First Parish until 1835 and one of the few people in town with a college education, would prepare students for college for a fee. There was also the Academy, a private school organized in 1796 by well-to-do parents who wanted to prepare their children for college. Cohasset finally established a public high school in 1826. At first, the town’s high school was so poorly funded that it shared a teacher with the Academy, and only operated when the Academy was not in session.

Cohasset finally established a school board in 1830, and that committee slowly improved the town’s public education offerings. By 1840, the “dame schools” had mostly given way to publicly funded primary education. It took longer to establish a year-round high school; it wasn’t until 1847 that the town finally provided funding to keep high school open for all year.

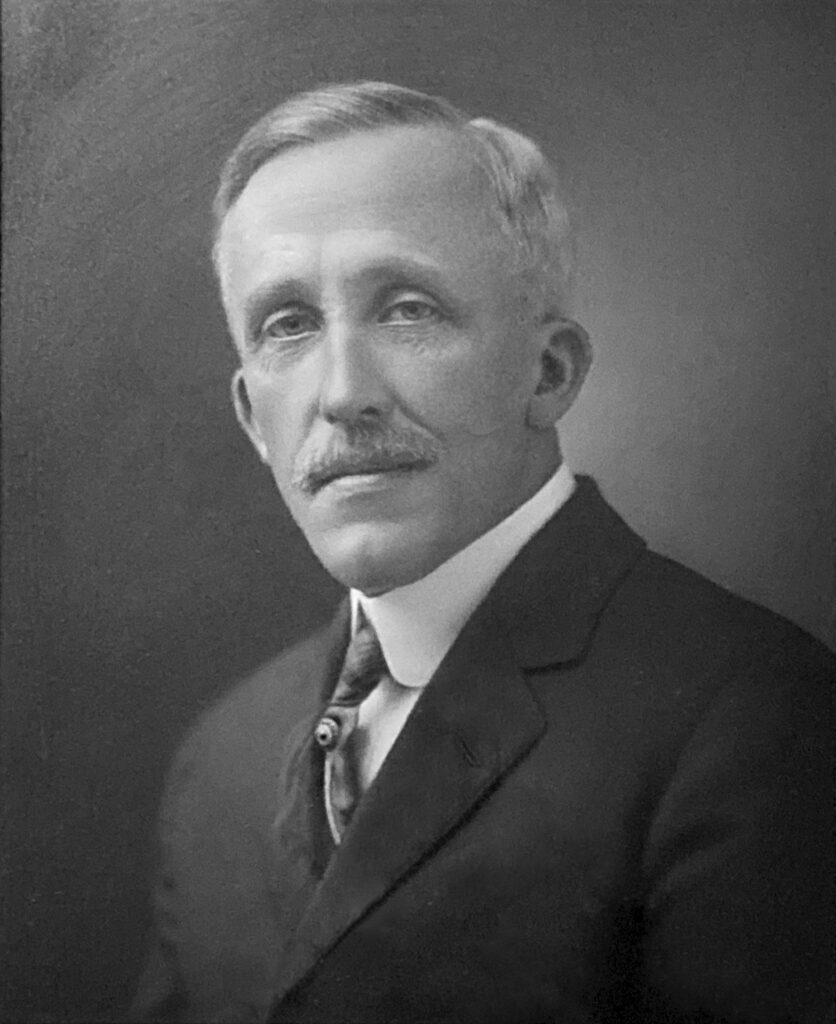

When our congregation hired Joseph Osgood as our minister in 1842, we specifically chose him because he had a background in education. According to town historian Victor Bigelow, Joseph Osgood brought about “uniform teaching and systematic promotion in our schools.” Osgood established graded classrooms and regular oversight of teachers. To support his efforts, Osgood could point to the work of Horace Mann. To train teachers, Mann had founded three so-called “normal schools” across the state; one of these normal schools was in Bridgewater (now Bridgewater State University). Mann also published “The Common School Journal,” a periodical filled with practical advice and best practices. No doubt Joseph Osgood read “The Common School Journal,” and (when he could) hired his teacher from the Bridgewater normal school.

Of special interest to us today, given what’s going on in public education elsewhere in the United States, is that both Osgood and Mann believed that publicly funded education should be non-sectarian. This did not mean that Horace Mannn believed that religion should be excluded from the public schools; it only meant that no one denomination or sect should have control over what was taught. In 1848, Mann wrote: “our system earnestly inculcates all Christian morals; it founds its morals based on religion; it welcomes the religion of the Bible; and, in receiving the Bible, it allows it to do what it is allowed to do in no other system — to speak for itself. But here it stops, not because it claims to have compassed all truth; but because it disclaims to act as an umpire between hostile religious opinions.”(1)

I think Mann was wrong in saying that public schools should be founded on Christian morals. In his own day, there were Jews and freethinkers in Massachusetts who did not wish to have their children inculcated with Christian morals. Even among the Christians of Massachusetts, it proved impossible to find common ground. Roman Catholics felt that Massachusetts public schools taught Protestant Christianity, with the result that they established Catholic parochial schools to provide appropriate schooling for their children; indeed, Catholics sometimes referred to public schools as “Protestant parochial schools.”

Yet although I don’t agree with everything that was done by the mid-nineteenth century educational reformers, people like Horace Mann and Joseph Osgood, I give them credit for greatly extending the reach of free public schools. Here in Cohasset, Joseph Osgood provided leadership to extend the school year, and to open the schools to as many children as possible. Over time, other educational reformers worked to further extend the reach of the public schools, and to further reform the content of public schooling.

One of those reformers was one of my personal heroes, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. A Unitarian and a teacher, Peabody became interested in the education of young children. She traveled to Europe to learn about a new educational approach called kindergarten. Peabody and other educators helped to establish kindergarten as an accepted part of the public school system, extending free schooling down to five-year-olds.

One of the people Elizabeth Palmer Peabody trained was Lucy Wheelock, who went on to found Wheelock College. My mother got her teacher training at Wheelock College while Lucy Wheelock was still active, and thus had a direct connection to Elizabeth Palmer Peabody. My mother was both a career schoolteacher and a lifelong Unitarian, and I’d like to use my mother’s example to talk about the connection between mid-twentieth century Unitarians and public education.

Unitarianism in the mid-twentieth century was deeply influenced by the Progressive movement. Please note that what was meant by “Progressive” back then is not what is meant by the adjective “progressive” today. The Progressives of that time (spelled with a capital “P”) wanted to reform human society: they believed in the essential goodness of human beings; they believed in the capacity of human beings to progressively establish a more just and humane society; they believed in the power of reason; they believed in democracy. They differed from today’s progressives (spelled with no capital “P”) in that the older Progressives founded their Progressivism in their liberal religious outlook; by contrast many of today’s progressives either have no religious outlook, or they try to divorce their religious outlook from their politics. I’d even say that the earlier Progressivism was not so much a political movement as it was a religious movement.

The wars and economic disasters of the mid-twentieth century caused many people to abandon Progressivism, to abandon their hope for progressively establishing a more humane and just human society. These other people turned to a grim view of humanity, and a grim view of human society; we can see some of this grimmer outlook in today’s political progressives.

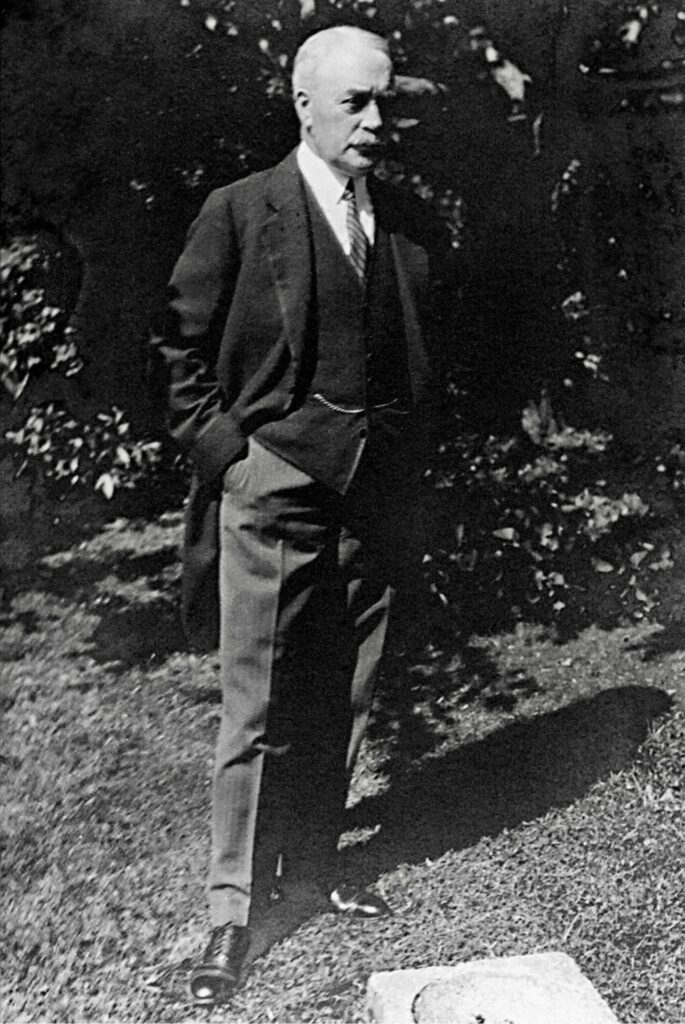

But we Unitarians and the Universalists, and some other liberal religious groups, held on to our belief that human beings are basically good. We held on to our belief that human society can be improved through human effort. My mother was one of that generation of mid-twentieth century Unitarians who believed we could make the world better. Like so many Unitarians of her generation, she and her twin sister both trained to become teachers. This was a classic strategy of Progressivism: to reform the world through education. With their sunny view of human nature, my mother and her twin were drawn to John Dewey’s educational philosophy. Dewey said that it was through public education that we could establish a truly democratic society. Dewey taught that “only free and continued education can counteract those forces which are always at work to restore, in however changed a form, feudal oligarchy.”

My mother’s idealism was quickly tested. She got her first job right after the Second World War ended, teaching kindergarten in the public schools in Fort Ticonderoga, New York. In 1946, Fort Ticonderoga was a backwater. At the end of her first year of teaching, the school principal told her that if she wanted to continue teaching in Fort Ticonderoga, she would have to begin to use corporal punishment. This went against my mother’s belief in progressive education. She found another job.

She wound up teaching in the Wilmington, Delaware, public schools when those schools were being desegregated. Once while she was walking down the street with her class, some men drove by and shouted racial slurs because she, a White woman, was holding the hand of a Black kindergartener.(2) The Progressive Unitarian teachers of the mid-twentieth century believed, with John Dewey, that “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.” In the 1950s and 1960s, the crisis in democracy centered on racial segregation; and educators and education were the midwives to a very messy birth of equal access to the public schools, all in service of strengthening democracy.

Today, seventy-five years later, we face a different educational crisis, and we Unitarian Universalists are still trying to figure out how to respond. The current presidential administration is in the news this week with their efforts to dissolve the U.S. Department of Education. While this act grabbed the headlines, it’s actually just one event in a longer history of efforts to privatize education. These efforts can be traced in part back to the work of the influential economist Milton Friedman. In 1955, about the time when thugs were shouting racial epithets at my mother, Milton Friedman wrote an essay titled “The Role of Government in Education,” in which he advocated for what he called school choice, based on a voucher system. School choice has been widely adopted both by both political and religious conservatives, and by political and religious liberals. Friedman’s ideas for school choice are rooted in his notion that economic freedom is the crucial freedom that a democracy needs to flourish.

We are in the process of discovering some of the downsides to school choice as promoted by Milton Friedman. School choice policies have encouraged for-profit companies to get involved in education. In theory, this is not a bad thing, but it has led to a definite tendency to establish financial profit as the most important goal of a school, rather than education. School choice also means that one city can see separate schools reflecting the values of a small group of families rather than the wider community. In theory, this is not a bad thing, and indeed Unitarian Universalists have used school choice to establish charter schools that reflect their ideals and values. But this goes against the notion that public schools are where we can learn to live with people who are different from us, an essential skill in a democracy.

At the same time, school choice could be a useful tool for promoting educational reform, because it allows for the testing of innovative ideas. If school vouchers existed in the day of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, perhaps she might have established a charter school to demonstrate that kindergartens really do benefit young children. Similarly, we can imagine John Dewey establishing a charter school, to show that the educational methods he first tried out in the University of Chicago laboratory school could also work in a public school.

And we do face some serious educational problems today. For example, the quality of the schooling a child gets depends a great deal on what city or town they live in. In 2023, the high school graduation rate in Cohasset, where I now live, was 98.3%; in that same year, the high school graduation rate in New Bedford, where I used to live, was 78.6%.(3) Nor can this disparity be explained solely by the per-pupil expenditures; for while Cohasset does spend more, at $23,212.40 per pupil in 2023, New Bedford is not that far behind, at $20,943.37 per pupil in 2023. The reasons behind these educational disparities in Massachusetts are hotly debated, and I’m certainly not qualified to end that debate. My point is simply this: educational reform is still necessary to ensure that all children have equal access to education, and to ensure an informed electorate which is necessary for democracy.

Unitarian Universalists used to see education as a key area where we could make a difference in helping to improve human society. After all, we are one of the top two or three most-educated of all religious groups; thus not only do we place a high value on education ourselves, but our educational attainments mean we should be able to help strengthen the educational system of this country. And as a religious group, we remain committed to education, both as a way to strengthen democracy, and as a way to allow human potential to flourish.

Yet it feels to me as though Unitarian Universalism, as a wider movement, has drifted away from seeing education as a key area where we can make a difference. In the past couple of decades, I’ve heard lots of Unitarian Universalists talk about their commitment to social justice, but I’ve rarely heard a Unitarian Universalist say that their commitment to social justice led them to get elected to their local School Committee, or try to influence state or local policy on education. Similarly, in the past couple of decades, I’ve often heard older Unitarian Universalists encouraging young people to go to college to “get a good job”; much less often have I heard older Unitarian Universalists encouraging young people to go to college so they can become teachers. And in our denominational publications, I read quite a bit about how we should be active in promoting justice, but I don’t read much about the importance of teachers and teaching and education.

Our own congregation is better at seeing education as a central way for us to make a difference. We have quite a few teachers and educators in our congregation, and we honor them and their profession. I’ve listened to older Unitarian Universalists in our congregation encourage young people to follow careers in teaching. A primary part of our mission as a congregation is operating Carriage House Nursery School, a progressive educational institution providing innovation in the area of outdoors education for young children. I should also mention that our congregation provides state-of-the-art comprehensive sexuality education for early adolescents and a week-long ecology day camp; these are both small programs, but they fill an educational need here in Cohasset.

In these and other ways, we’re continuing Joseph Osgood’s legacy. We still consider teaching and education to be a central part of our purpose; we still consider teaching and education to be a central part of how we contribute to the betterment of human society. It might be worth our while to be a little more forthcoming about taking credit for all the ways our congregation supports public education, supports early education, supports teachers, supports other kinds of education — and for us to be a little more forthcoming in taking credit for the way we are thus supporting and strengthening democracy.

Notes

(1) Horace Mann, Life and Works of Horace Mann, vol. III, ed. Mary Mann, “Annual Report on Education for 1848,” pp. 729-730.

(2) I don’t know when exactly this took place. My mother left Wilmington, Del., c. 1956; I can’t find out when primary schools were desegregated. One source I consulted said that desegregation didn’t occur until after the 1954 Supreme Court ruling; see: Matthew Albright, “Wilmington has long, messy education history”, The [Wilmington, Del.] News Journal, 10 June 2016 accessed 22 March 2025 https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/education/2016/06/10/wilmington-education-history/85602856/

(3) The Massachusetts Department of Education has a website where you can compare educational outcomes between school districts: go to the “DESE Directory of Datasets and Reports” webpage, click on “School and district performance summaries.” https://www.mass.gov/info-details/dese-directory-of-datasets-and-reports#school-and-district-performance-and-indicators-