I finally watched the BBC’s video clip showing the moments when the Republicans heckled Democratic president Biden’s “State of the Union” speech. Looks like heckling has now become a normal part of the “State of the Union” speech.

What interests me is the hecklers shouting about lies and lying. The first such heckler, if you remember, was the fellow who shouted out that Obama lied. This tradition was upheld this year by the Christian nationalist shouting “Liar!” at Biden.

Knowing what is true is a major concern for U.S. society right now. And those who are within a traditional Christian worldview seem to suffer most from a sense that truth is under attack. Traditional Christians who believe that non-Christians will go to hell are often troubled by the multi-religious landscape of the United States today; those non-Christian people are going to hell, and yet our legal system protects them. This must be extremely disconcerting to certain traditional Christian worldviews.

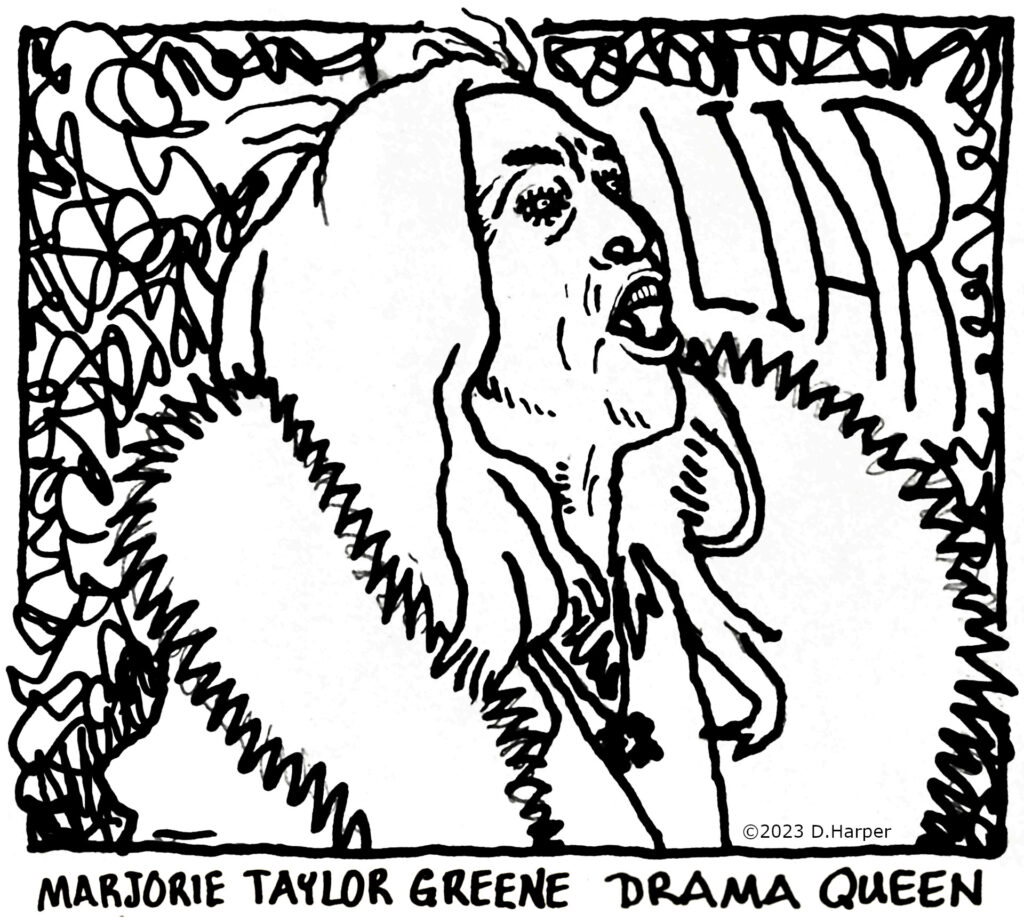

So it is no surprise that one of the people shouting about lies during this year’s “State of the Union” speech was Christian nationalist Marjorie Greene. I suspect that Greene, who’s a bit of a drama queen, prepared herself in advance for her moment in the spotlight: she wore a dramatic white coat with a big furry ruff, which must have been dreadfully hot but was clearly meant to set off her blonde good looks. And she so obviously enjoyed the moment when she made the audience turn and look at her. She seems to have forgotten, however, that when you shout, it distorts your mouth and face and throat, and it brings out all the little lines in your face making you look older than you are. (This is why I hate seeing videos of myself preaching.) No matter: she made her truth claim in a very public manner, that she knows the truth, and unless the rest of us agree with her she will shout us down as liars.

Back in 2005, philosopher Richard J. Bernstein argued that there were two prevailing mentalities in the United States. On the one hand there is a “mentality that neatly divides the world into the forces of good and the forces of evil.” On the other hand, there are those of us who “live without ‘metaphysical comfort,’ … live with a realistic sense of unpredictable contingencies” (The Abuse of Evil: The Corruption of Politics and Religion Since 9/11 [Malden, Mass.: Polity Press, 2005], pp. 12-13).

Greene and other Christian nationalists belong to the mentality that neatly divide the world into good and evil; they long for comfort and fear the unpredictability that pervades the world. Because of their fear, they cling to whatever certainties they can manufacture, and call those manufactures divine revelation.

But they should remember that when they shout, it distorts their faces….