While developing a curriculum for middle elementary grades, I found an interesting game, “Patol House,” originally played by Native Americans in New Mexico. I found this game in the book Handbook of American Indian Games by Allan and Paulette Macfarlan (Toronto: General Pub., 1958; reprint, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Pub., 1985). The Macfarlans are recreating games for use by middle class white kids in summer camps in the 1950s, and no doubt they have modified the rules to this game somewhat. I have further modified the rules, turning this into a board game suitable for use indoors in a multi-racial Sunday school classroom; and I further modified the rules to fill in a gap or two that we found in the Macfarlans’ rules during test play.

Sample game play with adults showed this can be a fun game. It’s supposed to be a game of skill and strategy, not of luck — the skill comes in being able to throw the counting sticks to yield the number you want; the strategy comes in planning your moves to “kill” opponents’ horses. In our sample play, we gained enough skill to throw the desired number maybe one out of ten times, so it was mostly a game of luck for us. But even as a game of luck, it was enjoyable to play.

With no further ado, here’s how to make and play the game:

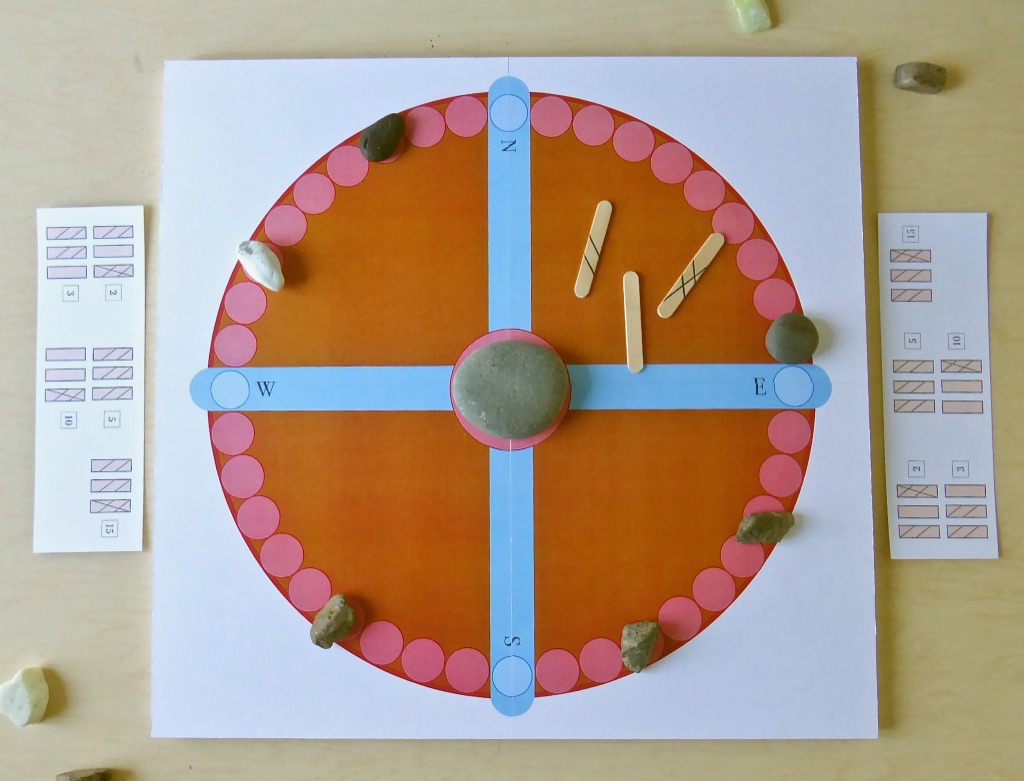

Making the game: According the the Macfarlans, the Indians used a game board of 40 stones arranged in a circles, with 4 gaps between the stones; the gaps are “rivers.” The design shown in the photo below reproduces this game board on paper; the blue stripes are the “rivers.” I printed the design in halves, on two 11 by 17 inch pieces of cardstock; then gluing the cardstock to foamcore to make a 17 by 17 inch game board. The counting sticks are popsicle sticks that are shortened; the sticks are marked (based on Tiwa Indian designs) as follows: all three sticks have two hatch marks on one side; two are left blank on the reverse side, while one is marked with three hatch marks on the reverse. A flattish stone goes in the center; this is to bounce the counting sticks off. I made two cards showing how to score the throws of the counting sticks. For playing pieces, I found some small stones, as you can see in the photo below; however, these were not very satisfactory, and I have since substituted colored game pawns.

(Notes on making the game: 1. The point of this game is not to try to recreate an utterly authentic Native design, but to make a game that is easily playable. 2. The file for the game board is something like 5400 x 5400 pixels at 300 dpi and too big to post here, so you’ll have to draw your own game board. 3. I’m prototyping the game using the Board Games Maker Web site; when they ship it to me I’ll post a photo on this blog.)

This game works best with 8 or more players. If you have fewer players, give each player two horses; players take a separate turn for each horse.

Setting up the game:

Put the stone in the center of the game board. The playing pieces, called “horses,” remain off the game board until a player plays them.

Throw the counting sticks to see who goes first:

Hold the three counting sticks in your hand about a foot above the game board. Bring your hand down, and release the sticks about 6 inches above the stone (but no closer). The sticks hit the stone, bounce, and fall with one face or another showing.

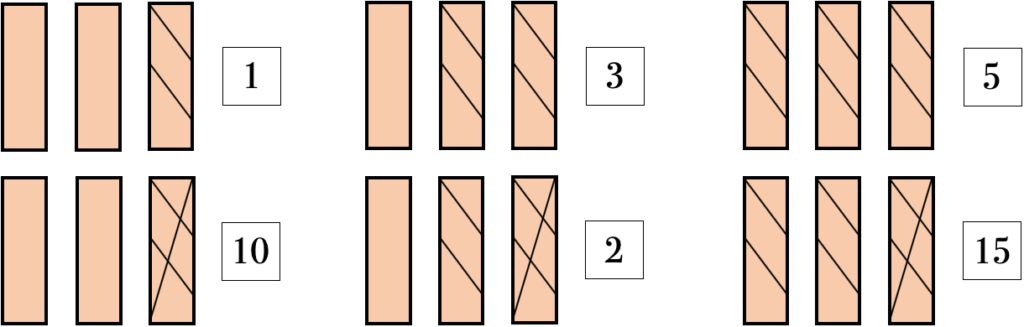

The diagram below shows how many points you get, depending on which sides of the counting sticks are showing. The player with the highest number of points goes first.

Game play:

The first player throws the counting sticks, and, starting from a blue circle nearest to where they are sitting, moves their horse that number of spaces. Players may move either clockwise or counterclockwise as they wish, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction in subsequent turns. However, if they throw a 10, this would place their horse in a river. Horses may not land in rivers. Whenever a throw lands their horse in a river, the player must throw the counting sticks again until they throw a number that will not land their horse in a river.

The other players may begin from the same river that the first player started from, or from a different river. Again, they may move either clockwise or counterclockwise, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction.

Player’s horses may pass over other players horses. But if one player’s horse ends up on the space occupied by another player’s horse, the other player’s horse is considered dead and must start over. A player may have to start over several times during the course of a game.

If you start over, you must start in the same river you started in before (that is, in the same blue circle). However, if you start over, you can again choose to go either clockwise or counterclockwise—though again, once you choose a direction you have to keep going in that direction, until you have to start over again.

Winning the game:

The first player whose horse makes it all the way around the circle, back to their starting point or past it, wins the game.

Strategy: For good players, this is a game of skill. A good player can hold the sticks in their hand and bounce them in such a way as to get the number they want. But be sure to release your hold well above where the sticks hit the stone, so you’re not accused of cheating.