I feel like such a grouch. I keep writing blog posts about ways the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) could be more transparent in the ways it handles clergy misconduct. But I’m not one of those people who post criticism of the UUA but who aren’t looking for actual improvement, they just want to badmouth the UUA. My purpose is different. I actually like the UUA. But like all human institutions, the UUA could be better, and I’d like to contribute in some small way to making it better. Since I have no skills for committee work or denominational governance, what I do is write about possibilities for improving the UUA.

So I’m really not a grouch. I hope.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking about ways the UUA could be more transparent in its handling of clergy misconduct. And I’d like to point out three other religious groups who inspire me with their attempts to be more transparent.

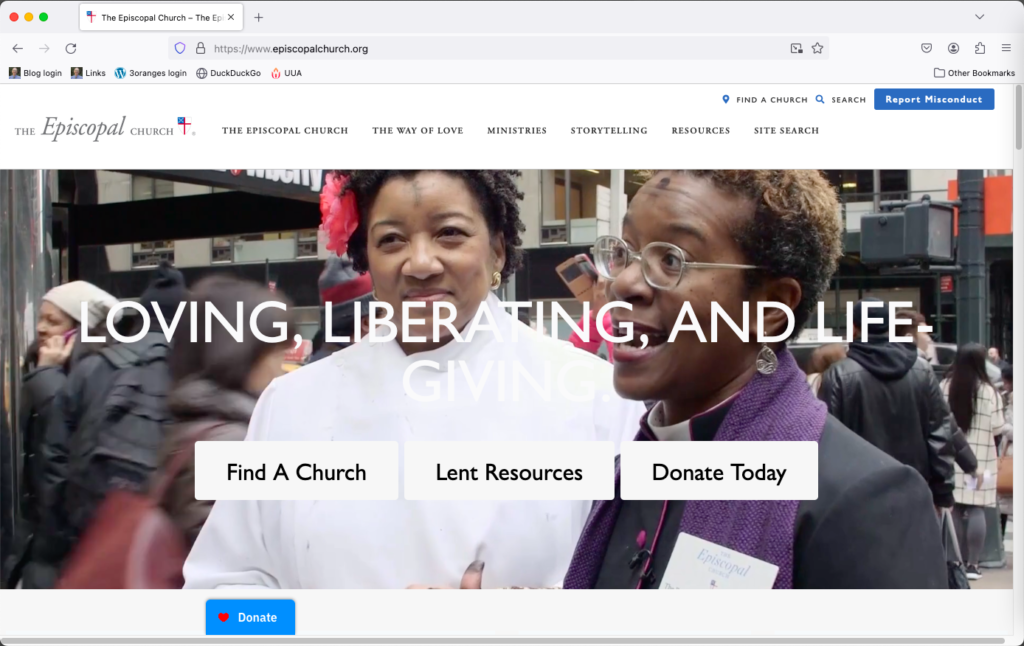

First, I’d like to point out the website of the Episcopal Church here in the U.S. Take a look at the screenshot below that shows the front page of their website:

It’s a little hard to see in my screen grab, but in the upper right hand corner there’s a prominent button that reads “Report Misconduct.” If you click on that button, you are taken to another webpage with detailed and (to my mind) confusing instructions about how to report misconduct by clergy. Indeed, there has been criticism from within the Episcopal Church about how their actual processes are not especially transparent.

But forget about their problems with their internal processes for a moment. I applaud their decision to post a prominent link on the very front page of their website that takes you right to instructions on how to initiate a complaint about clergy misconduct. Contrast that with the UUA website, which has no such prominent link. I find it very difficult to locate any information on the UUA website about how to initiate a complaint regarding clergy misconduct.

One final point — given all the publicity around clergy sexual misconduct in the past twenty years, it seems to me to be a smart marketing move by the Episcopal Church to have that prominent link on their front page. It says to people who are looking for a religious home — “We’re serious about stopping clergy misconduct.” It signals that they might be a safer religious home than, say, Unitarian Universalism.

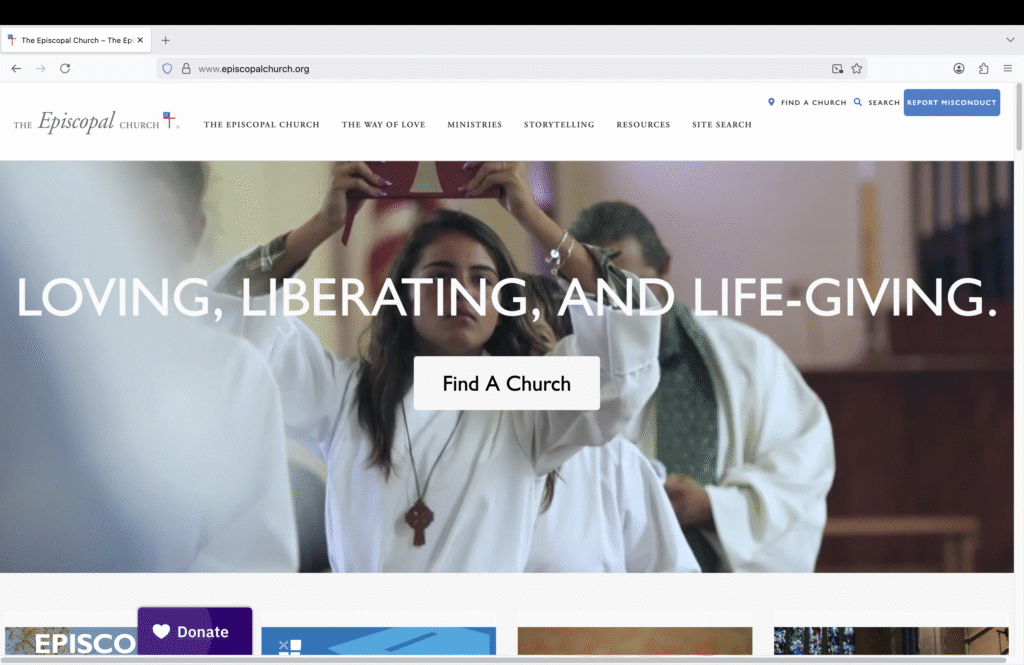

Second, I’d like to point out this webpage from the Rabbinical Assembly, the organization for Conservative Jews in the U.S. The webpage is titled “Rabbis Expelled or Suspended from the Rabbinical Assembly for Ethical Violations”:

On this page, freely visible to anyone visiting their website, the Rabbinical assembly lists the names of seven rabbis who were expelled from the Rabbinical Assembly since 2004. This is exactly what should happen — if a clergy is expelled from a denomination of association of congregations, then the denomination-level website should make their names freely accessible in the interests of transparency.

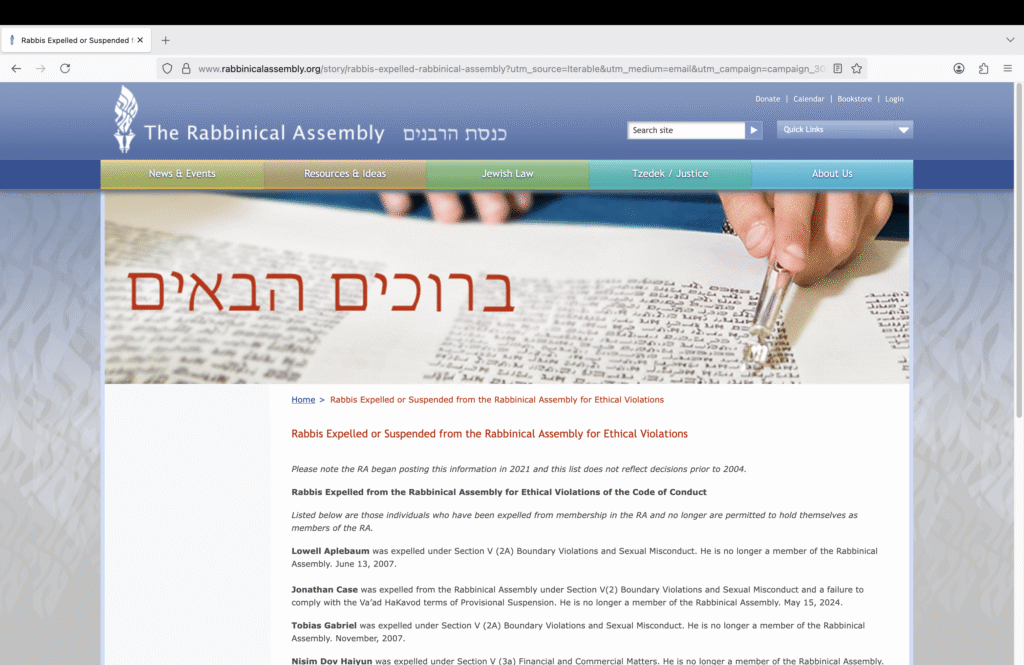

The UUA tried doing this for a while, beginning in 2021. Then, a couple of years ago, that list was hidden from public view. You can still see a webpage titled “UUA Credentialed Religious Professionals Resigned or Removed from Status Due to Misconduct” on the UUA website — but when you get to that page, you are instructed: “To access the list of ministers removed from fellowship by the Ministerial Fellowship Committee, Ministers who resigned fellowship pending misconduct reviews, and religious educators whose credential was terminated by the Religious Education Credentialing Committee, you must log in or register.” You can just about read these instructions on the screen grab below:

I can understand why this page has been restricted —I imagine that in an era of increasing violence, the UUA has the admirable goal of keeping names and personal information hidden. But there are several names that do not need to be hidden, such as ministers who have been convicted of sex offenses, so that their misconduct is a matter of public record. Examples include David Kohlmeier, Ron Robinson, and Mack Mitchell. In addition, this webpage should clearly state why access to the list is restricted — I’ve imagined a charitable reason why the UUA has hidden this page, but someone else could imagine the UUA has hidden the list for nefarious reasons.

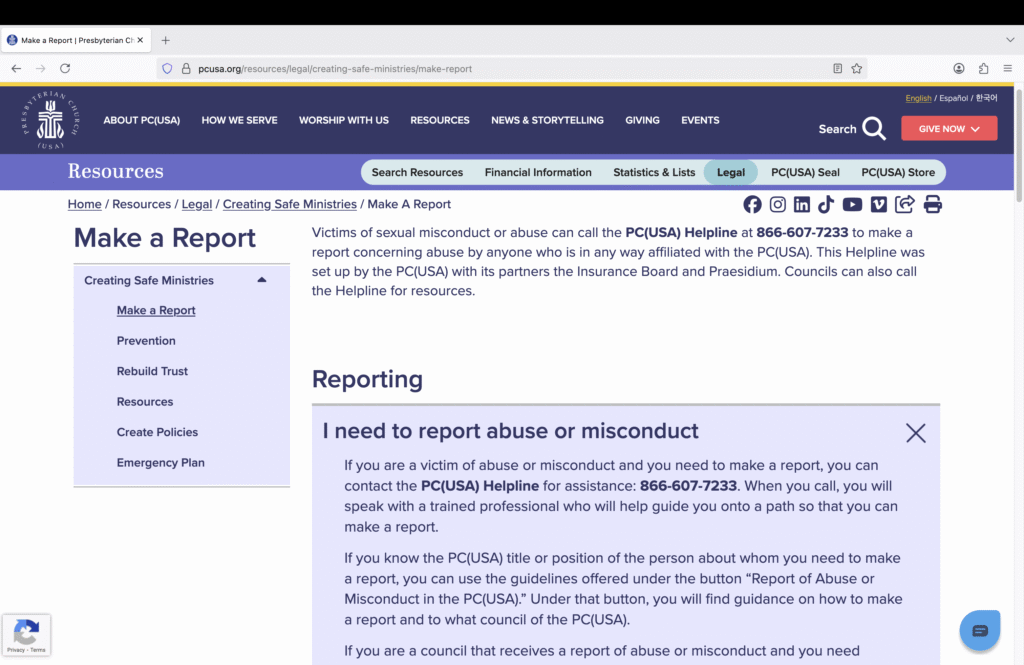

Third, the Presbyterian Church USA actually has a phone hotline that you can use to report abuse, as shown on this screen grab:

Admittedly, there are all kinds of potential problems with this helpline. Most obviously, who is the “trained professional” who answers the helpline? If it’s a denominational staffer, someone paid by the denomination, I’m going to be skeptical of their ability to remain neutral; I’d hope the “trained professional” is actually employed by their insurance carrier (which seems to be implied here), because an insurance carrier is somewhat more likely to take misconduct allegations seriously. Also, I could wish that the helpline would offer both voice calls and texting (I hate talking on the phone, but I love texting). And finally, I would like to see a guarantee of confidentiality — please tell me that if I call, and I feel uncomfortable with the “trained professional,” that you’re not going to track me down through my phone number.

Nevertheless, this makes it really easy to report misconduct, and I applaud this attempt at making the reporting process as transparent as possible. (I also applaud the fact that the “trained professional” can also provide information about abuse prevention resources — great idea.)

How might this apply to the UUA? Here are three practical suggestions — and the first two are actually very easy to implement.

First, the UUA should have a prominent link on the landing page of their website that with one click provides specific, actionable instructions on how to report misconduct.

Second, at least a partial list of ministers removed from fellowship should be publicly accessible on the UUA website without requiring registration — and there should be a clear explanation of why seeing the full list requires registration.

Third, ideally the UUA would provide an easily accessible service for reporting misconduct. And ideally, this service will be provided by an independent contractor, not by a denominational employee.