I had to get to Saco, Maine by one o’clock, which meant I had to start driving by about six in the morning. I managed to get up and get on the road by ten after six. By the time I got to central Massachusetts, traffic started getting heavy, and it was stop-and-go in several places. But I made it to Saco in time for the one o’clock meeting for children’s staff for Religious Education Week at Ferry Beach Camp and Conference Center, somewhat frazzled, but ready to spend the week doing nature and ecology activities with children.

Mentor, Ohio, to Utica, N.Y.

Of course I got a late start again today, and I had to get the oil changed in the car as well. So I planned to get the oil changed, then get on the road as quickly as possible, with no delays and not stopping.

But the James Garfield National Historic Site was a quarter of a mile from the place where I got the car’s oil changed. As I was driving to the interstate, I couldn’t resist stopping in. A tour was just starting, and they let me join it.

Garfield, if you remember (I hadn’t remembered until the tour started) only served as president of the United States for four months before he was shot. He received inadequate medical care for the wound, lingered for nearly three months, then died.

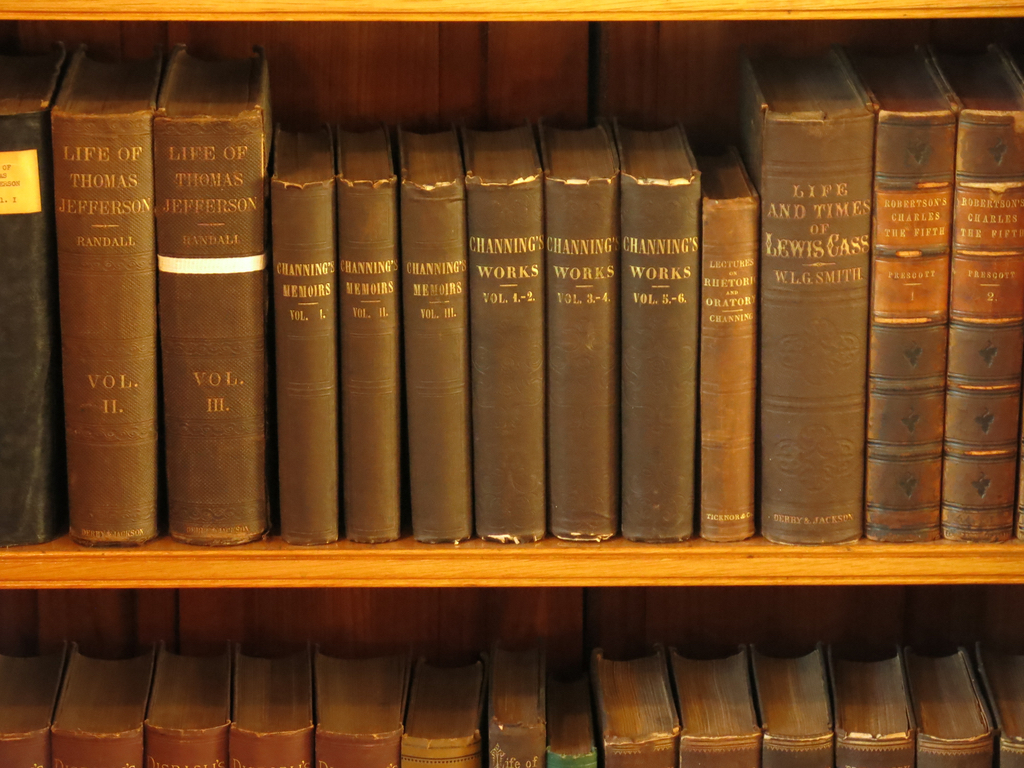

We toured the Garfield house, which they called “Lawnfield,” and from the front porch of which Garfield gave numerous campaign speeches. After his death, his widow Lucretia more than doubled the floor area, creating a James Garfield memorial presidential library to hold all his books and some of his papers. While our excellent tour guide told us about the room and its contents, I looked at the books, and spotted both Channing’s memoirs, and his complete works.

Garfield was baptized into the Disciples of Christ, so he didn’t own these books because Channing was a Unitarian; any well-read progressive Republican politician of the mid-nineteenth century might have had Channing’s works.

My favorite room was called, if I heard the name right, the “Snuggery.” It has a comfortable reading chair, a desk, a couple of other chairs for visitors, and a fireplace over which is the motto “In Memoriam,” the poem by Tennyson, one of Garfield’s favorite poems.

It was worth the time to stop and see Lawnfield, and I liked it so much I’d like to return some day. But of course that stop meant I arrived at my hotel later than I had hoped, and I have to get up at five tomorrow morning so I can be in Maine by one in the afternoon….

Joliet, Ill., to Mentor, Ohio

Another day when I got up late. I decided not to feel bad about it, because I had lost two hours in the past few days from crossing into more easterly time zones.

I grabbed a cup of coffee and drove immediately to Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, which was just a few miles from the motel in which I spent the night, eating breakfast as I drove. I parked at the Goff Road trailhead, and at first I thought I had made a poor choice. I walked down a paved road, partially overgrown at the edges since it was only used by bicycles and farm equipment and National Forest Service trucks. The prairie on either side of the road has not yet been reclaimed here, and is still being farmed for soybeans. I thought about driving to another trailhead, but it was too late for that so I kept walking.

And soon I decided that I had made the right choice. The relatively wide paved road, along with a light breeze, seemed to keep the biting insects away, and it also afforded excellent views into the trees and brush that had grown up between the road and the soybean fields. Even though it was hot, even though it was the middle of the day, there were birds everywhere, and that’s what I had really come for. I turned to look up in a tree just as a Yellow-billed Cuckoo landed on a branch above me, a large green insect, maybe a grasshopper, grasped firmly in its bill.

I walked for about a mile and a quarter, taking my time and looking for birds. I was dripping with sweat. It was time to turn back.

Not long after I turned back, a man on a bicycle pulled up beside me, and asked if I knew why the road was closed where I had turned back. I said that I had seen on the Midewin Web site that there were unexploded munitions and other hazards in parts of the land. It turned out that the man on the bicycle has been in the National Guard for something like twenty-five years, and in his early days he had had training sessions on what is now Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie but was then a military base.

We kept talking. I think he was happy to ride slowly, as slow as my fast walk. He said he had just gotten the bicycle; he was a deputy for the Will County Sheriff’s Office, and had recently taken training on bicycles for police; I finally noticed that his bike said “POLICE” on it in big letters. I asked him how he liked it, and he said that while he liked it, it didn’t do so well on some of the gravel roads he encountered in Midewin; but we agreed that every bicycle is a compromise.

We talked for most of a mile back to the parking lot. He told me about coming across some cows wandering in Midewin while he was riding a couple of days ago, and I told him about the handwritten sign I had seen on the gate at the trailhead: “Please close the gate, my cows are loose in here.” I showed him the map of Midewin posted at the trailhead, and told him how I downloaded one from their Web site. We shook hands, both said how much we enjoyed the conversation, and then as I was getting in my car he said, like a good police officer, “Drive safe!”

The rest of the day consisted of a mix of construction areas with stop and go traffic, construction areas with people driving too fast, and — every now and then — clear roads and easy driving. between the construction, and crossing into the Eastern Time Zone, I found myself getting further and further behind schedule. I decided I had better look into returning via Interstate 70, to avoid the horrendous backups at Chicago. But I had hoped to drive up into Michigan — the one state of the lower forty-eight that I have not yet been to — on the return trip.

There is one exit between the Indiana Toll Road and the Ohio Toll Road, and on a whim I got off there and drove north a few miles till I was well inside the Michigan border, then turned around and drove back to the interstate. That put me even further behind schedule, and it was ten thirty when I finally pulled in to the motel in Mentor. Carol had texted me earlier in the day: “Mentor, OH — I was a girl there. Look for the rose farm.” But it was dark and I was late, and I did not see a rose farm.

Avoca, Ia., to Joliet, Ill.

Yet another late start. After driving for just two and a half hours, it was time for lunch. I stopped in Colfax, Iowa, and went in to Poppy’s Restaurant. It was lunch hour, and there were half a dozen parties of men, working stiffs, some wearing blaze yellow shirts, some wearing ball caps. Some of the guys talked back and forth from one table to the next. At the table next to mine, two younger men talked seriously about whatever job they were on, then one of them made a call on his cell phone and spoke in the jargon of a trade I wasn’t familiar with.

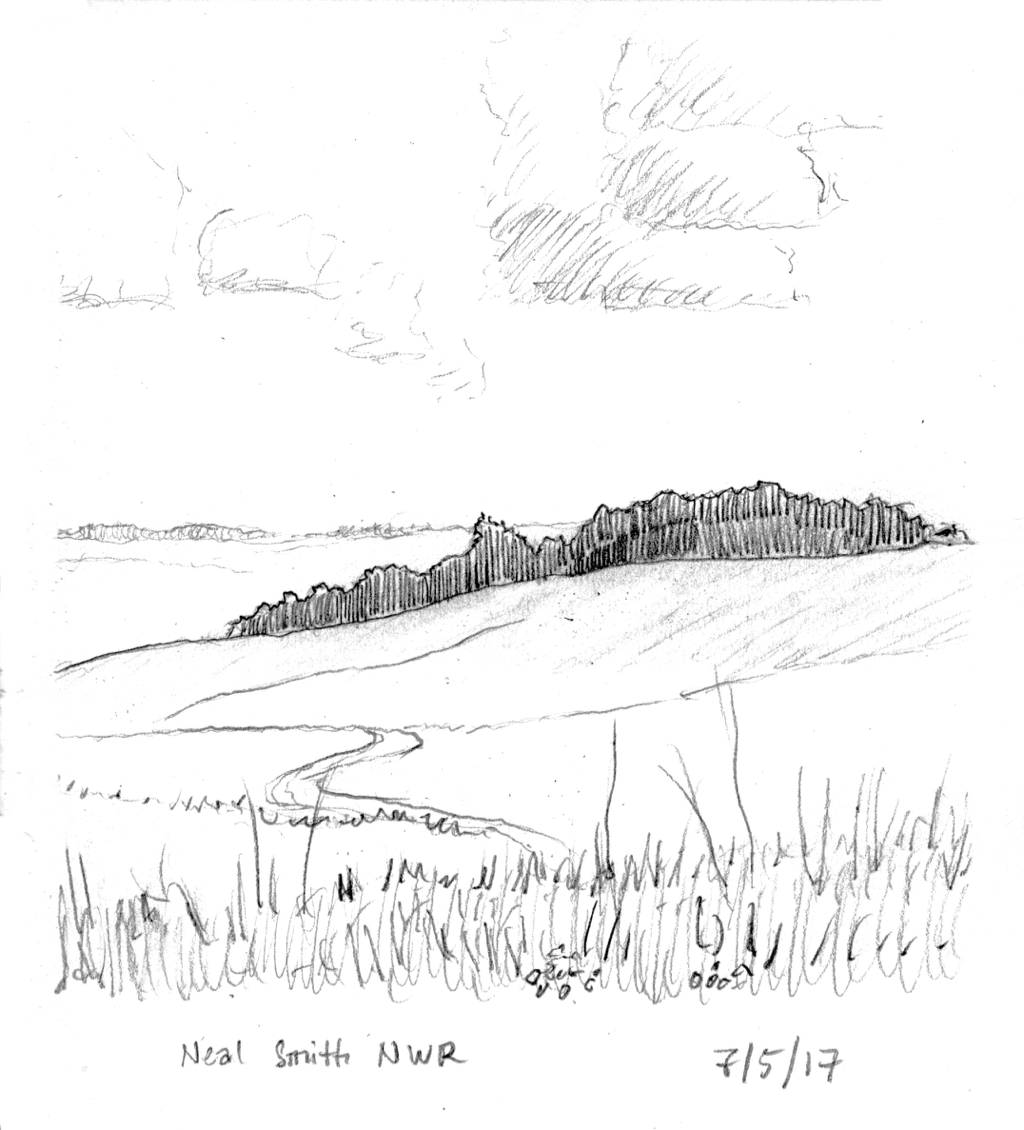

I drove south from Colfax to Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, a restored prairie with some oak savanna. Seven hundred acres of the refuge are fenced off and a small bison herd lives there, while scientists study the impact these large mammals had on the prairie ecosystem.

At the visitor center, I spent half an hour talking with a man, probably half my age, who worked for the Department of the Interior. We talked about long distance hiking trails, and I learned from him that the National Park Service now administers the North Country Trail, stretching some 4,600 miles from North Dakota through New York to the Vermont border. He also waxed enthusiastic about the Florida Trail, administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which currently extends for 1,000 miles through Florida. I told him he should take a sabbatical from his job and hike one of those trails, and he said he takes winters off and last winter he went to Nepal.

I could have spent more time listening to him talk, but I wanted to get outside. I went out into the hot humid summer day and walked two nature trails, one through oak savanna and one that started high on a prairie hillside then dropped down into a riparian corridor with small willows and a mostly dry stream. Dickcissels were everywhere, Indigo Buntings flew through the lower branches of the oaks, Field Sparrows sang in the grass, and I watched an Orchard Oriole feed its young. A checkerspot butterfly basked in the shade, on the front of a concrete bench.

Before I got back into my car, I stopped to look at the landscape of the restored prairie and oak savanna. The contours of the land were what you’d expect of central Iowa, rolling hills and valleys with small streams. But without the usual dark green covering of soybeans or corn, the landscape took on a different aspect: it was lighter in color, and the air was filled with bird song. I tried to imagine Iowa without any farms, with great herds of bison grazing on the prairie, but it was hard to do so; this is a landscape that we humans have altered almost beyond recognition in the past century and a half.

And tonight I’m staying in Joliet, in the growing sprawl of Chicagoland, where malls and housing developments have replaced corn and soybeans. It’s even harder to imagine this landscape as it must have been before Europeans settled here.

Sidney, Neb., to Avoca, Ia.

Dreams, dreams, dreams. Some of the dreams were unsettling, though I don’t remember specifics, and when I awoke I sat for a moment dazed. It was almost nine o’clock. By the time I started driving it was ten thirty. And in less than a hundred miles I entered the Central Time Zone and lost another hour. I abandoned plans to visit Ash Hollow State Historical Park to see the tracks of the Oregon Trail, because I couldn’t afford the extra hour of driving.

I drove until lunch time, and stopped at a Denny’s. A decade ago, I would have passed Denny’s by, because many of their restaurants refused to serve black people, but supposedly they have mended their ways. My server was a talkative young black man, who lacked the usual carefully defended manner of many servers in interstate truck stops. He was the father of an eight month old — his face lit up when he talked about his son — and he was filling in at Denny’s while getting a paid holiday from his regular job as a lawn tech.

When I stop for meals, I’m re-reading Isaac Asimov’s memoir, I. Asimov. He wrote it in 1990, a couple of years before he died. At the time he wrote it, he was quite ill from the complications of AIDS; he had been infected by a blood transfusion in the early 1980s, though this wasn’t revealed until well after his death. Asimov puts his finger on exactly what his peculiar genius was: he was unbelievably prolific as a writer; but beyond that, he makes no real claims to fame for himself. He loved to write, and he was fortunate that what he liked to write sold well enough to make him a millionaire. The real fascination in his memoir is the degree to which he reveals himself and assesses himself. He cheerfully calls himself vain, arrogant, self-absorbed, and nasty (p. 383), and he was most certainly sharp-tongued. But he also comes across as thoughtful, driven, fearful, and kind. I especially admire his evident kindness, a kindness which had distinct limitations but which was genuine and rooted deeply within him.

By the middle of the afternoon, it became obvious that I was not going to make it to DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge before dark, since it lay well off the interstate. But I needed a walk, so I stopped where I’ve stopped before, at Rowe Audubon Sanctuary on the Platte River, just five miles from the highway. It was pleasantly hot and a little bit humid. I saw and heard eastern birds that I haven’t seen since the last time I drove west through Nebraska: Blue Jays and Eastern Kingbirds and Northern Bobwhites.

I walked for an hour and a half, and went back to driving. I was listening to an audiobook of The Pickwick Papers, but part of my mind was occupied with thinking about my father’s life. I can hardly escape such thoughts, since a primary reason for this trip back east is to go through what’s left of his papers. And that makes me think about my own life, and I wonder how I will someday describe myself, as Isaac Asimov described himself, assuming I ever get to a stage of life where I have greater perspective on myself. — From such thinking, I suspect, came last night’s dreams.

As the sun was setting, I drove up through the Loess Hills of western Iowa, a landscape that is both familiar and unexpected at the same time: fields of Iowa soybeans and corn on steep hillsides whose shift in perspective can mislead one into thinking the hill is steeper, or less steep, than it really is. This could serve as a metaphorical representation of last night’s unsettling dreamscape.

Evanston, Wyo., to Sidney, Neb.

Last night, Will texted me to say he and Linda were driving west on Interstate 80, and where was I? I texted him back saying that I was in Evanston. That’s where we are, replied Will. We arranged to meet for breakfast. Be sure to bring your Sacred Harp book, Will said.

The place that served breakfast in downtown Evanston was closed due to the holiday, so we wound up in the motel where Will and Linda had stayed. I will undoubtedly see Will and Linda at a Sacred Harp singing sometime this year, and when we do see each other we will talk about the same things we talked about at breakfast — how Will’s wife is doing, how Linda feels to have completed her Master’s degree — but how much fun it was to sit and talk as the result of the coincidence of staying in the same town on intersecting cross-country trips!

Linda had to go take care of her cats, but Will and I stayed in the breakfast room of the motel to sing a song or two. Will wanted to sing a traveling song, so we sang “The Promised Land”: “I am bound for the promised land. / Oh, the transporting, rapt’rous scene, / That rises to my sight, / Sweet fields arrayed in living green, / And rivers of delight.” We kept it soft and gentle, so as not to disturb anyone else, and when we had finished talked about how much fun it can be to sing with control and delicacy.

A woman thanked us for singing. We said she was welcome to join us, and she said she would love to; though she wasn’t much of a hymn-singer, even though she was a Christian. We sang “Wondrous Love,” thinking she might know the tune, but she didn’t, so she sight-read the harmony as best she could, improvising in places, in her mellow soprano voice. Then she said she knew “Amazing grace,” so we sang that in three parts. She asked where we had come from, and we told her about our coincidental meeting; she told us that she had lived in Evanston for many years, but now lived in Texas and was back for a visit. And with that, we all had to get going. I drove off feeling the best I’d felt on this trip so far.

I stopped at Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge, and went for a walk near Six Mile Bridge. Within a quarter of an hour, I had seen what I had hoped to see: ten or a dozen Greater Sage-Grouse flushed noisily up and flew low over the sagebrush. I stopped to look at some Milkweed that was blooming and counted at least six different pollinators: bees, something that looked like a wasp, and a butterfly. (The photo below shows at least two different pollinators.)

The air was cool, and the sun was hot and bright and cheerful. A slight breeze mostly kept the mosquitoes and deer flies away. A Golden Eagle flew low over the trees on the other side of the Green River, driven to flight by the attacks of smaller birds. In the reeds at the edge of the river, a Moose (Alces alces) browsed the vegetation, chewing big mouthfuls of leaves from the bushes and trees.

Two Mountain Bluebirds flew along an irrigation ditch, looking spectacularly bright. A Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) skulked through some bushes, trying very hard not to be seen by me. Swallows swooped through the air, moving so fast I could only positively identify Cliff Swallows and Tree Swallows, though I thought I saw Northern Rough-winger Swallows and Violet-Green Swallows, too.

At last it was time to go, and regretfully I got in the car and starting driving east again. Some day I’d like to spend a week at Seedskadee; but not this year, I’m on a tight schedule. I drove the rest of the day, stopping for lunch and dinner, and pulled into Sidney, Nebraska, just in time to see the beginnings of a fireworks display. I watched it from the motel parking lot for ten minutes, then checked in to the motel, drawing the clerk away from the front door where she had been watching the fireworks. She put me in a second floor room that gave an even better view of the fireworks. I called Carol, who loves fireworks, and told her what I was seeing.

And then it was time for bed.

Winnemucca to Evanston, Wyo.

I got on the road at nine, but I wasn’t feeling completley alert, and I kept pulling over to get out and stretch. I tried listening to an audiobook of the Pickwick Papers, but I couldn’t stay focused. I listened to some Renaissance music for a while, then a field recording of old Sacred Harp singing, then Steve Reich, then John Coltrane — but each in turn quickly grew annoying. I tried singing the bass part of a duet I’m learning, but I skipped over a part then couldn’t remember the words. I stopped at one place to take a walk, but it was beastly hot, so I got back in the car and drove. I stopped for lunch at the rest area on the Bonneville Salt Flats. An hour later I stopped for a quick walk at Tempe Spring Wildlife Area, but the Black-Necked Stilts were aggressive and I soon saw why: shy young Stilts were hiding in the reeds, trying to be invisible; so I left. I stopped at a reservoir in Echo Canyon, only to realize that the column of black smoke I saw was a burning tractor trailer rig on the west-bound side of the highway, right over the road I drove under to get to the reservoir. I took a forty-five minute walk, and when I got back to the car the tractor was still burning, surrounded by fire trucks. Finally I drove into Wyoming, into self-proclaimed Big Sky Country — which weakly describes a landscape that makes human affairs feel tiny and insignificant — glad to put an end to this day.

San Mateo to Winnemucca

Today is the first day of a holiday weekend, and of course traffic was horrible. By the time I got to Davis, it was half past noon. So I stopped for lunch at Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area.

It was so pleasant there — clear, a light breeze, temperature in the low eighties — that I decided to spend an hour walking around. There is very little standing water, except in the rice fields and along the riparian corridors. I walked along one of the riparian corridors, listening to the bullfrogs and enjoying the coolness that emanated from the willows. An American Bittern flew over my head. Some kind of unremarkable-looking plant with white flowers was in bloom between the edge of the road and the willows. An urgent humming sound rose from the flowers: scores, maybe hundreds of tiny metallic green bees flew from tiny blossom to tiny blossom flowers, moving so quickly it was hard to see one, except as a metallic green blur.

I got back on the road, and the traffic was heavy through the Sierras. Some of the peaks still had a little bit of snow on them. Every year when I drive through the Sierras, there are fewer and fewer pines and firs, as the trees succumb to the various effects of global climate change: invasive species that thrive on warmer temperatures, changing weather patterns, and so on. Parts of the Toiyabe National Forest could now be called the Toiyabe National Bare Ground.

After Reno, the traffic grew light. Now way behind schedule, I stopped for dinner in Fernley, and ate at a very mediocre Chinese restaurant. I started driving again just after six, when the sun was getting lower in the sky; this is the best light for the glories of the Humboldt Sink and the mountains along the Humboldt River. I needed a walk, and I stopped at Rye Patch Reservoir near Imlay. At 7:30, it was still hot, over ninety degrees, but the air was dry and filled with the scent of sagebrush.

I walked half a mile down a gentle canyon to the reservoir. Jack rabbits burst from cover and scampered away from me. Cattails and willows grew along the bottom of the canyon. Six or eight Common Ravens talked among themselves on the ridge over my head. A Great Blue Heron flew silently up the canyon away from the water, and a Mule Deer leaped up over a rise and quickly disappeared from my sight.

Carol couldn’t come with me on this trip, but she bought me a sketch book to take along. I decided I had better use it, and when I got back to the car I made a sketch of the start of the dirt road down to the reservoir. The sketch smudged easily, and when I got to Winnemucca I stopped at Walmart to get some sprayable fixative. Walmart is a remarkable place, filled with many things that catch and hold your attention, but in contrast to Yolo Bypass or Rye Patch Reservoir, the only organisms I saw at Walmart were human beings.

Pounding flowers

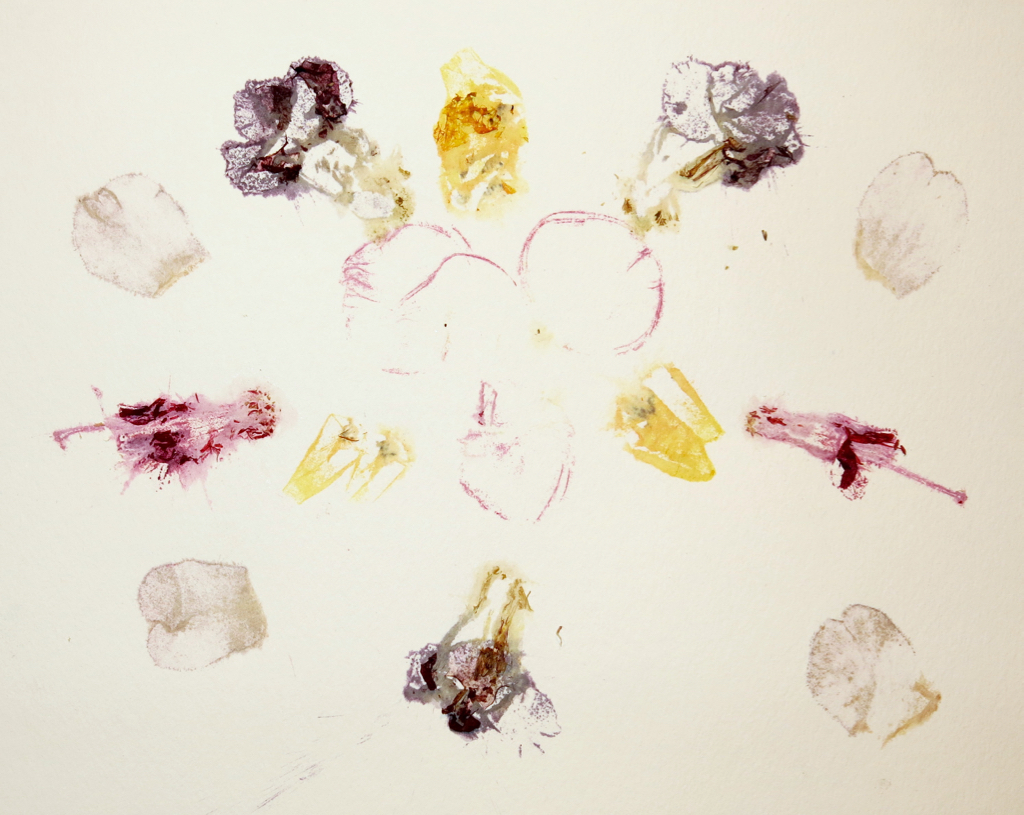

One of the best projects we did in Nature Camp last week was “Pounding Flowers,” a project from the book A Little Bit of Dirt: 55+ Science and Art Activities To Reconnect Children with Nature by Asia Citro (Woodinville, Wash.: Innovation Press, 2015), pp. 72-73. The idea is to collect several different flowers, arrange them on a piece of watercolor paper, cover them with paper towels, and pound the heck out of the flowers so that they release their juices which are then absorbed by the watercolor paper.

Our campers, who were ages 6-7, particularly enjoyed pounding the flowers with rubber mallets. So did we adults: the feel of the impact of the rubber mallet on a hard concrete floor was satisfying in itself, and the addition of the flowers sandwiched between towels and watercolor paper was even better.

(Photo courtesy of Ecojustice Camp; parents provided a media release for this child.)

But I was not entirely satisfied with this project myself. The paper towels did not work very well; they tended to shred under heavy pounding, and the flowers tended to shift under them. So tonight I tried something different. I collected some flowers; arranged them on a piece of watercolor paper on a smooth concrete surface; then instead of paper towels I laid another piece of watercolor paper over the arrangement, and pressed gently down.

This worked extremely well. It was even more satisfying to pound on, because the top piece of watercolor paper didn’t shred, and it didn’t shift much. When I was done, I got two pieces of pounding art, mirror images of one another. And, best of all, this process yielded more detail of the flowers: I got distinct outlines of the petals or pistils in some cases.

This was a very fun process art project to begin with, and by sandwiching the flowers between two pieces of watercolor paper it got even better.

Update, July 15, 2025: For a more sophisticated version of this art project, see my post on hammer dyeing.

How to fight therapeutic technological consumerist militarism

The current issue of Geez magazine (“Contemplative Cultural Resistance”) just arrived in my mailbox from Canada, and the issue opens with a quote from Walter Brueggeman’s 2005 essay “Counterscript.” Geez had to abridge the quote, but here’s the original:

———

“The dominant script of both selves and communities in our society, for both liberals and conservatives, is the script of therapeutic, technological, consumerist militarism that permeates every dimension of our common life.

“I use the term therapeutic to refer to the assumption that there is a product or a treatment or a process to counteract every ache and pain and discomfort and trouble, so that life may be lived without inconvenience.

“I use the term technological, following Jacques Ellul, to refer to the assumption that everything can be fixed and made right through human ingenuity; there is no issue so complex or so remote that it cannot be solved.

“I say consumerist, because we live in a culture that believes that the whole world and all its resources are available to us without regard to the neighbor, that assumes more is better and that ‘if you want it, you need it.” Thus there is now an advertisement that says: ‘It is not something you don’t need; it is just that you haven’t thought of it.’

“The militarism that pervades our society exists to protect and maintain the system and to deliver and guarantee all that is needed for therapeutic technological consumerism. This militarism occupies much of the church, much of the national budget and much of the research program of universities.

“It is difficult to imagine life in our society outside the reach of this script; it is everywhere reiterated and legitimated.”

———

Later in the essay, Brueggeman goes on to say that this script has “failed,” for “we are not safe, and we are not happy.” He points to the complicity of the Christian church in “enacting” this script, adding:

“It is the task of the church and its ministry to detach us from that powerful script.”

Unitarian Universalism got kicked out of the Christian church more than a century ago (a fact we’re now kind of proud of), but like many Christian churches we too are enacting the script of therapeutic technological consumerist militarism. We firmly believe that we can find ways to live our lives with no inconvenience. We firmly believe that we can find a fix for every problem.

The next two points may not be as obvious, and will require some explanation.

We may protest that we fight consumerism, but we live our lives as though resources are ours to exploit. We cut down on our oil use, but we firmly believe that the sun and wind are ours to exploit for energy. We say we are anti-racist, but the financial health of many of our congregations can be traced back to seed money accumulated through exploitation of people of color: land appropriated from Native American peoples, labor appropriated from persons of African descent, etc.

We may protest militarism. Many of us may be peaceniks, and some of us have been arrested protesting militarism. But in the end we depend on systems that protect therapeutic technological consumerism, and so we protest that upon which our livelihoods depend.

Brueggeman goes on to say: Continue reading “How to fight therapeutic technological consumerist militarism”