Busy sidewalk in Oakland. Woman talking on cell phone.

“Ballet is good for girls.”

Pause.

“It makes them polite.”

Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

Busy sidewalk in Oakland. Woman talking on cell phone.

“Ballet is good for girls.”

Pause.

“It makes them polite.”

Alfred Salem Niles (1894-1974), professor of aeronautic engineering at Stanford [note 1], helped start the present church — then Unitarian, now Unitarian Universalist — after the Second World War. In 1958, he wrote this detailed memoir of how our present church began. Since he was one of the few people to attend both Unitarian churches in Palo Alto, his memoir helps connect those of us in the present-day church with the early Palo Alto Unitarians.

I am publishing only the 500 words of this 11,000 word essay here. The complete essay will soon be available in print form at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto.

The Spring of 1947

In 1927 when the writer came to Palo Alto, the old Unitarian Church at Cowper St. and Charming Avenue was still functioning, but rather feebly. The minister was a woman who later gained considerable notoriety as a fellow-traveler, though her proclivities along that line were not yet apparent [note 2]. There was no Sunday School that I know of, and attendance at the morning services was small. In earlier years the church had been much more active, but the minister at the time of World War I had been a pacifist and conscientious objector, and this had caused a split in the church from which it never recovered. Another thing which I think was an important obstacle to recovery was the quality of the pews in the old building. They were the most uncomfortable ones that I have ever encountered. Since mortification of the flesh does not appeal to Unitarians as a technique of salvation, those seats must have discouraged many possible members. Morning attendance got so small that we tried having services in the evening. But that did not help. Our woman minister resigned, and for a while we had a student from the Starr King School preach to us. Finally, about 1929, services were discontinued, and after a few years the church organization was dissolved, the church building returned to the American Unitarian Association, (3) which sold it to a Fundamentalist group for about $230 less than the mortgage, and there was no more organized Unitarianism in Palo Alto for several years.

During the 1930s the Chaplain at Stanford was Dr. D. Elton Trueblood, a Friend [i.e., a Quaker] with quite liberal views and an excellent speaker. Many Unitarians got into the habit of attending services at the Stanford Church as a result. But he resigned and was succeeded by more orthodox men, and most of the Unitarians in town lost the church-going habit. One result of this was that quite a few of us, although well acquainted with each other, did not realize that we were fellow-Unitarians. The writer can testify to his own surprise, in 1947, to find that the head and one of the professors of his department at Stanford were also Unitarians. We just had never discussed religion with each other.

In the autumn of 1946, Rev. Delos 0’Brian came to San Francisco to be the American Unitarian Association (A.U.A.) Regional Director for the West Coast, with the objective of reviving some of the dormant Unitarian churches and organizing new ones in favorable locations. I was then a member of the Church of the Larger Fellowship, and noticed an item about Mr. O’Brian’s activity in the Christian Register for November 1946. It was not until some time in February 1947, however, that I went to see him at his office at the corner of Sutter and Stockton Sts. It was about noon when I got there, so we went across the street to the Piccadilly Inn to have lunch and talk about the possibility of starting something in Palo Alto. He had the names of about a dozen members of the Church of the Larger Fellowship in Palo Alto, and a similar number in San Mateo, but had not yet made many contacts with those in either group, and was undecided as to which one to start and I think it was my visit which caused him to decide to start with Palo Alto, and that the revival of the Palo Alto Church started at that meeting….

Continue reading “A new Unitarian church in Palo Alto, 1947”

A continuation of a documentary history of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

After the departure of Rev. Bradley Gilman, the congregation managed to get back on its feet, first with no minister, then with the experienced leadership of Rev. Elmo Arnold Robinson, a Universalist minister. But the financial situation worsened through the late 1920s, the congregation began to decline, and the Great Depression made it impossible to continue.

An Experiment in Palo Alto (1920)

[In the previous post, the excerpt from Josephine Duveneck’s autobiography told how the relationship between Rev. Bradley Gilman and the congregation grew strained. It is worth noting that Palo Alto was the last congregation that Gilman served. This chapter begins with an explanation of how the Palo Alto church experimented at having an entirely lay-led congregation. Edith Mirrielees asserts that the reasons for not hiring a minister were not financial, leaving us to conclude that Bradley Gilman soured the congregation on ministers.]

The Unitarian church in Palo Alto was established in 1905. From its establishment until the autumn of 1919, the church followed the way of most Unitarian churches, retaining a resident minister and supporting him with an enthusiasm that waxed or waned according to the circumstances surrounding the individual pastorate.

In May, 1919, the Rev. Bradley Gilman, at that time the incumbent, left Palo Alto for a visit to the Eastern coast. Some months later he sent in his resignation. When the congregation came together to consider the resignation, many of its members felt unwilling to begin the search for a new minister until an experiment had been made in conducting the church in another manner. For some years there had been a growing conviction among members of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that the presence of a professional minister was not necessarily essential to the continuance of their church or to its welfare, and after thorough discussion in congregational meeting it was determined to do without one, the pulpit to be tilled by members of the congregation and community or by visiting Unitarians. the other duties of the pastorate to be assumed by the congregation. It is worth noting that this decision was not reached because of money difficulties. The church at this time, though by no means wealthy, was in sound financial condition, without debt and with as many contributors as it had had during the previous year when a minister had been in residence. It should be noted, too, that the essential Unitarianism of the church is in no way affected by the change; the congregation is a congregation of Unitarians, but one wherein congregational government and responsibility is now carried a step farther than it has been before.

The attempt was at first frankly experimental. After four months of trial, it seems so far to have justified itself that there is at present no probability of a return to earlier conditions. Throughout the winter months, the pulpit has been regularly filled, often by speakers with a notable message, membership in the church and attendance at services have both materially increased, money has come in in quantity sufficient to meet all obligations and to make possible the establishment for next year of a scholarship at Stanford University, which it is the hope of the congregation to continue from year to year.

Rut these things, though they are encouraging, are only the outside results of the experiment. More important than any one of them is the effect of the change upon the relation of members of the congregation to the church and to each other. A new unity of purpose, an increased sense of fellowship, has been the most promising growth of the last few months. The presentation from the pulpit of many points of view 1ms promoted that tolerance essentially dear to Unitarians. The necessary sharing of responsibility has, as it is likely to do, increased the willingness to take responsibility. It goes without saying that the work has not been equally shared; as is the case in practically every congregation, one or two members have carried the heaviest part of the burden, but in very considerable number — a number much larger than was normally found under the old condition — have taken some part, with a resultant growth in actual neighborliness and interdependence.

It is by no means the thought of the Unitarian Society in Palo Alto that other bodies of Unitarians would necessarily be wise to follow in their footsteps. For any congregation, the wisdom or unwisdom [sic] of such an attempt depends upon the nature of the community in which the church is situated. It has to be a community which provides a fair number of thoughtful speakers; it has to be a congregation blessed with at least one member ready steadfastly to put the church’s welfare before his own, and neither of these things is easy to find. For Palo Alto, however, the experiment thus far has been promising enough to justify its further trial.

— Edith R. Mirrielees, The Pacific Unitarian (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), vol. 29, no. 5, May, 1920, p. 125.

[Note: Mirrielees was professor of creative writing at Stanford, and a teacher of John Steinbeck (Jeffrey Schulz and Luchen Li, Critical Companion to John Steinbeck [Facts of File: 2005), p. 301.]

A continuation of a documentary history of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

The years of the First World War proved difficult for the Palo Alto Unitarians. It was a congregation full of pacifists, but after the entry of the United States into the World War, the American Unitarian Association demanded that every congregation that received funding must support the war wholeheartedly. A financial report of the A.U.A. published in the June 6, 1918, issue of The Christian Register (p. 19) shows that the A.U.A. was paying their minister of the time, Bradley Gilman, $50 a month, or $600 a year.

The Palo Alto Unitarians had been accustomed to the pacifist views of former ministers Rev. Sydney Snow and Rev. William Short, but the war years forced them to accept the pro-war ministry of Bradley Gilman. The relationship with Gilman appears to have been strained; he left after only two years, and never served another congregation as minister; and the Palo Alto Unitarians tried to do without a minister for nearly two years.

New Unitarian Pastor (1915)

The church at Palo Alto has called to the vacant pulpit Rev. William Short, Jr., now in Boston, and highly recommended by those who know him, and also know the requirements of the church calling him. Mr. Short has accepted the call and will enter upon his ministry on the third Sunday of November.

— The Pacific Unitarian, vol. 15, no. 1, November, 1915 (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), p. 7.

New Unitarian Pastor.— A reception in honor of the new Unitarian church pastor, Mr. William Short, Jr., who has recently arrived from the east, was held in the Unitarian church hall last evening.

— from “Palo Alto Notes” in The Daily Palo Alto [Stanford], vol. 47, no. 58, November 18, 1915, p. 3.

———

A “Centre of Liberalism” on the Peninsula (1917)

Palo Alto, Cal.— Unitarian Church. Rev. William Short, Jr.: The Palo Alto church has had a very interesting two years with Rev. William Short, Jr., as minister. Although new to the service, Mr. Short has brought to it an earnestness and vigor, and a great broad humanity, which have meant to the church increased growth in those principles upon which it is founded. In this tremendous national crisis, when the democracy of the country is on trial, the Palo Alto church has been one of the very few where the privilege of complete freedom of speech in the pulpit has not been restrained. The membership of the church is small, about forty in number, and the lack of moral support due to isolation from other centres of liberal thought is very keenly felt. The nearest sister church is in San Jose, eighteen miles distant, and the next nearest in San Francisco, over thirty miles in the other direction, the dominating note in the theology of the region being definitely conservative.

The congregation is of a vigorous and thoughtful kind, avoiding a deadly conformity of opinion. It has maintained its stand for the universal character of religion. The pamphlet-rack in the vestibule must be constantly refilled. In conformity with its Unitarian heritage, the church hall has given hospitality during the past winter to Mr. John Spurgo, the noted Socialist speaker; to the American Union Against Militarism, which is earnestly fighting the cause of democracy; and to Mme. Aino Malmberg, a refugee from the persecutions of Old Russia and an ardent advocate of the cause of oppressed nations. Two physical training clubs for women and girls have had their home in the hall, as well as a dub to encourage the finer type of social dancing. The church passed a resolution of approval of the visit of Mr. Short to Sacramento in March in the interests of the Physical Training bills. The Women’s Alliance at its annual meeting was fortunate in having as guests Dr. Franklin C. Southworth and Mrs. Southworth and Secretary Charles A. Murdock. It has been the privilege of the church to welcome to the pulpit Rev. Charles F. Dole of Jamaica Plain, Mass. His sermon was “The Religion Beneath All Religions.” The church, probably in common with most others, has suffered somewhat from the mental and financial depression due to war conditions, though the members realize the importance of maintaining its integrity as the only centre of liberalism in a wide extent of country.

— The Christian Register (Boston: American Unitarian Association), vol. 96, no. 29, July 19, 1917, p. 694.

———

Denial of Writ of Habeus Corpus for William Short (1918)

[The following is excerpted from the hearing for a writ of habeus corpus filed by Rev. William Short’s wife, following his arrest and detention on charges of draft evasion. The Peoples’ Council mentioned in the writ was a national pacifist organization headed by Scott Nearing.]

Ex parte SHORT.

(District Court, N. D. California, First Division. September 5, 1918.)

No. 16417.

In the matter of the application of the wife of William Short for a writ of habeas corpus to secure his discharge from the custody of military authorities. Writ denied, and Short remanded to the custody of military authorities. …

DOOLING, District Judge. The wife of William Short seeks his discharge on habeas corpus from the custody of the military authorities. The record shows that Short, who will be designated herein as the registrant, on January 14, 1918, returned to his local exemption board his questionnaire, in and by which he claimed exemption as “a regular or ordained minister of religion.” In support of such claim he stated:

That “he had been admitted to Unitarian ministerial fellowship In January, 1916, at Palo Alto, Cal., and that on June 5, 1917, he was minister of Palo Alto Unitarian Church.”

To the question, “State place and nature of your religious labors now,” he returned no answer; but in response to the question, “Give all occupations at which you have worked during the last 10 years, including your occupation on May 18, 1917, and since that date, and the length of time you have served in each occupation,” he answered:

“Unitarian minister 1 year and 10 months. From May 15 to June 25, Unitarian minister, time included above. Chairman Northern California branch Peoples’ Council (temporarily) 5 months. Student for balance of time during 10 years.”

Upon these answers he was placed in class VB; that is to say, in the class of a regular or duly ordained minister of religion.

On June 6, 1918, a letter was sent to the local exemption board by the United States attorney, stating that registrant — “registered for the draft at Palo Alto on June 5, 1917. At that time he was acting as a minister in the Unitarian Church of that town, but shortly thereafter resigned from the church and has not been connected in any way with any church since, but has, on the contrary, devoted his time to the activities of the Peoples’ Council, which organization is decidedly unpatriotic in my opinion. I believe that Short should be reclassified and compelled to do military service, other things being equal.” …

From this reclassification he appealed to the district board, which on June 15th denied the appeal.

Thereafter, and on July 19, 1918, he was arrested and on July 20, was by the local board for division No. 1 in San Francisco, certified as a deserter, and delivered to the commanding officer of the United States army, and now is in the custody and under the control of such officer. …

Registrant has suffered no injury at the hands of the local board, and the writ of habeas corpus is therefore discharged, and he is remanded to the custody of the military authorities.

— The Federal Reporter: Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit Courts of Appeals and District Courts of the United States (St. Paul: West Publishing Co.), Dec. 1918-Jan. 1919, vol. 253, p. 839.

Rev. Clarence Reed served longer than any of the other ministers of the old Palo Alto Unitarian Church, for six years from 1909-1915. Arguably, these were the best years for the congregation: they built the social hall that had been originally planned; the Sunday school grew to perhaps 60 children and teenagers; the Women’s Alliance had perhaps 40 members; and perhaps 200 adults were affiliated with the congregation. Here are documents that tell the story of the congregation during these years:

Rev. Florence Buck in Palo Alto (1910)

[Rev. Florence Buck was one of the better known women who served as Unitarian ministers in the early part of the twentieth century. During her brief stay at Palo Alto, she inspired at least one teenaged girl to become a minister — more on that teenager in a subsequent post on the Palo Alto Unitarians.]

Rev. Florence Buck has been given a year’s leave of absence at Kenosha, Wis., and is supplying the pulpit at Palo Alto, Cal.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), October, 1910, p. 5.

Mr. Reed, the minister of the Palo Alto Society, has been ill, but hopes to take up work again in December. His pulpit mean-time is being supplied by Rev. Florence Buck.

— Unitarian Word & Work (Boston: American Unitarian Association), November, 1910, p. 8.

WOMAN MINISTER TO FILL PULPIT

Rev. Florence Buck Has Been Chosen Pastor of Unitarian Church of Alameda

Alameda, [Calif.,] Dec. 19. — Rev. Florence Buck has accepted a call to become the minister of the First Unitarian church of this city. She will begin her pastorate Sunday, January 1, on which date she will conduct services and deliver her initial sermon. She will be the first divine of her sex to take permanent charge of a local church and will be one of the few women ministers in service on the Pacific coast.

The new minister is unmarried. She has had extensive experience In religious work and has been a preacher of the Unitarian faith for some years. She was associated with Rev. Marian Murdock in conducting a church in Cleveland, O. She also filled the pulpit of a Unitarian church in Kenosha, Wis. Of late Rev. Miss Buck has been temporarily occupying the pulpit of the Unitarian church in Palo Alto in the absence of the regular minister, Rev. Clarence Reed, former pastor of Alameda Unitarian church, who is on a vacation in Japan. Since Rev. Mr. Reed left here and went to the Palo Alto church the First Unitarian church has been without a regular pastor. Rev. J. A. Cruzan, field secretary for, the Unitarian society or America, has been acting temporarily. Rev. Miss Buck was heard here twice in the pulpit: of the Unitarian church last month. On both occasions she made a good impression and the trustees decided to extend her a call.

— San Francisco Call, vol. 109, no. 20, December 20, 1910, p. 11.

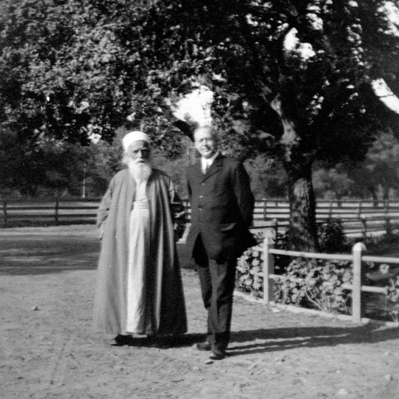

Above: Rev. Clarence Reed and the Baha’í prophet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palo Alto, 1912

Here are documents that tell the story of the early years of the old Unitarian Church of Palo Alto.

The Women’s Alliance (1906)

PALO ALTO.

Branch Alliance of the Unitarian Church, 25 members.

Pres., Mrs. Agnes B. Kitchen, 912 Cowper St., Palo Alto.

Vice-Pres., Mrs. Isabel Butler, 853 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto.

Sec., Mrs. Isabelle Wocker, 853 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto.

Treas., Mrs. Emily S. Karns, P. O. Box 148, Palo Alto.

Ch. Cheerful Letter, Mrs. Jessie B. Palmer, 765 Channing Ave., Palo Alto.

Includes all the women’s organizations of the church.

Committees: Hospitality, House, Decoration, Entertainment, Work.

Meetings second and fourth Tuesdays at 2 P.M.

Money raised, $205.15. Disbursed: $8.35 to National Alliance; $150 for church lot; $6 for hymn books; $25.98 for materials. Organized October 21, 1905.

— Manual, 1906, National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Woman (New York, Knickerbocker Press, 1906), p. 168.

The New Church Building (1907)

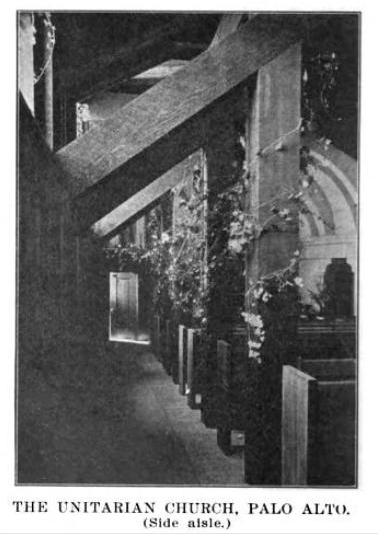

The most important event in the department of church extension during the past month was the dedication of the new church-building at Palo Alto. This occurred on Sunday morning, March 24th. It was a home affair, simple, but very interesting to the faithful Unitarians who have worked so hard and sacrificed so much to bring the enterprise to a successful termination. The erection of this church was made possible by the generosity of Mrs. Frances A. Hackley, of Tarrytown, N. Y., who has done so much for the Unitarian cause in this department. The members of the church entered into the work with a determination to make the new church-building not only useful but beautiful and convenient. The interior of the new church is all that could be desired; the exterior will not show its merit until the vines grow over it, as the vines are an essential part of the plan. The services in dedication were well attended.

— The Pacific Unitarian, vol. 15, no. 6, April, 1907 (San Francisco: Pacific Unitarian Conference), p. 165.

Above: The old Unitarian church, designed by Bernard Maybeck (from The Pacific Unitarian, May, 1907, p. 206)

Continue reading “The Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, 1905-1909”

Below is a list of the charter members of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, organized on November 12, 1905. This list is taken from Donna Lee’s transcription, found in her 1991 history of the old Unitarian church. I believe she made some transcription errors; unfortunately the original document appears to have been destroyed, though a photocopy definitely exists, and at some point I will look at the photocopy to try to check the accuracy of Lee’s transcription.

In the mean time, I have been doing some research on these early Palo Alto Unitarians. The majority of them are associated with Stanford — students, faculty, staff; and spouses and parents of same. There are several people I have not been able to track down; let me know if you happen to know anything about them.

The list of charter members is below…. Continue reading “Charter members, Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, 1905”

The documents below tell the story of Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes and her efforts to start a Unitarian organization in Palo Alto, in the years 1895-1896. (Though a Universalist, she was at that time working for the Unitarians.)

Wilkes first came to the Bay area in 1890: “By the early 1890s, as heart problems and a hectic schedule caught up with her, Wilkes began to spend the winter months in California. During the winter of 1890-91 she served the Alameda, California, Unitarian Church.” [Article on ETW, http://www25.uua.org/uuhs/duub/articles/elizatupperwilkes.html accessed Oct. 10, 2013, 14:32 PDT]

———

In 1893, she began serving as Rev. Charles Wendte’s assistant in Oakland. “It should be added that when, in 1893, Mr. Wendte reassumed the Unitarian superintendency for the coast for two years more, he invited Rev. Mrs. Eliza Tupper Wilkes to become his assistant and substitute during his absence. Mrs. Wilkes greatly endeared herself to the congregation during her eighteen months of earnest and efficient service.”

— The Unitarian (collected ed., Boston: George Ellis), March, 1897.

———

Since hiring Wilkes allowed Wendte to hold down another paying job, as the Pacific Coast superintendent for Unitarians, he had to pay her out of his own pocket. She was charged with overseeing the Sunday school, pastoral calling, adult organizations, and she was asked to do occasional preaching. Wilkes resigned from Oakland in March, 1895. “Her health had not improved, and Wendte could not afford to pay her.”

— Arnold Crompton, Unitarianism on the Pacific Coast (Starr King Press / Beacon Press, 1957), p. 151.

———

By November, 1895, the Pacific Unitarian reported that the Women’s Unitarian Conference voted to continue its support for Wilkes’s missionary work. At that time, she was living in Berkeley.

— “Notes,” November, 1895, vol. 4, no. 1 (San Francisco: ), p. 6.

———

According to Doug Chapman, Wilkes “was the first woman to preach at the Stanford University Chapel — in May, 1895. Her sermon was titled ‘Character in the Light of Evolution’.”

— “Dakota Territory’s Eliza Tupper Wilkes: Prairie Pastor,” paper delivered at the Dakota Conference on History, Literature, Art, and Archaeology, Augustana College, 2000. [For an account of this sermon, see this blog post.]

———

The Woman’s Club was addressed, at its last meeting, not by Miss Holbrook as advertised, but by Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes, of the First Unitarian Church, Oakland. Not having a special address prepared, she was asked to speak of Woman’s Clubs. She said they were in no sense an achievement but a prophesy: the worst use to make of them is as a mutual admiration society, as has been done. That they are needed is an advertisement to the world that women have not yet found their place. Until this is accomplished and men and women stand on the same plane in our meeting Woman’s Club will be a necessity as a means to an end. Separate clubs are a training school for women. In these they hear their own voices, learn executive ability, and gain experience. Yet such clubs are one-sided, disjointed affairs.

As a mother of six children she spoke from experience when she said that mothers needed relief from their home duties, hence she would not have the club a mother’s meeting but a meeting of mothers; a place where they should not hear so much of their own duties, but something of the duties of fathers, if need be. but particularly of outside things, of literature, science, art, that they might take home with them some thought to brighten the daily routine.

— The Palo Alto Times, vol. 3, no. 18, May 10, 1895, p. 2.

———

Mrs. Wilkes will hold Unitarian services at Parkinson’s Hall, Sunday afternoon, November 3rd, at 4 o’clock. All are invited.

— The Palo Alto Times, vol. 3, no. 44, November 1, 1895, p. 3.

Continue reading “Documents on Eliza Tupper Wilkes in Palo Alto”

This sermon by Rev. Eliza Tupper Wilkes (1844-1917), preached at Stanford, comes from “The Sunday Sermon,” a weekly summary of the sermon preached at Stanford printed in the Daily Palo Alto of Stanford University, vol. 7, no. 78, Monday, May 6, 1895, p. 1. This reads like someone’s careful notes of the sermon; it is too awkward, and far too short, to be an actual reading text. Nevertheless, it gives a good sense of how Wilkes preached late in her career.

The sermon also gives a opportunity to see one way an experienced evangelist made herself known in a community. She doubtless chose to address the topic of evolution because it would be a topic of interest in a university chapel. In less than six months, Wilkes had gathered a group of Unitarians and other liberals, who then formally organized as a Unity Society (not a full church, but a lay-led society) in January, 1896. The Unity Society did not last long, but it laid the groundwork for the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, which was organized in 1905, and lasted until the Great depression.

———

The sermon Sunday morning was preached by Mrs. Eliza T. Wilkes of the First Unitarian Church of Oakland. The subject was “The Forgiveness of Sins in the Light of Evolution.”

Do not think I do not realize the awful presumption of speaking to you on such a subject. A short time ago a minister asked me if I believed in evolution. I said most certainly I did so far as I had gone. Sin has been considered the choice of the imperfect for the perfect. Today most of us regard it as a crime against life. Your body, complete in every function, is a model body. Violating anything which retards this, is sin; retarding life is immorality and bin. Dying to live is full complete life. A criminal has more to hope for than the licentious person. We see all around us the results of sin. It is as much a sin to think wrong as it is to do wrong.

Evolution, with its awful fact of heredity, emphasizes the old law that the father’s sins descend upon the children. Children suffer for sins not only of the father but of the third and fourth generations. It emphasizes the curse against wrong-doers. We are not living in a universe of goodness. Hell cannot be put off. “Whatever a man soweth that he reapeth.” Are we held hand and foot in the inexorable grip of vice? Cannot we get free? Must the prodigal son be stricken from the gospel’s pages? True, there are no longer any punishments left in our philosophy, only consequences. Are there no evangelists for us to see? Are there none to save the captive and to help the lost?

A few months ago I was preaching in a room over a saloon. A friend who always waited to see me home was standing in the doorway. I preached on the well known subject, “Salvation Through Character.” My sermon sounded void and empty, but when I reached the door my friend, who drinks, gambles, and according to the old saying, “whose worst enemy is himself,” said, “I like those sermons on character, but how about us poor devils who haven’t any?” We must ask that question or stop preaching. If the philosopher can not help those poor ones who need help we had better stop and tell again the old, old story.

Life has in it a re-creating force. Life brings to us sweetest results: it takes the scar and destroys every sign. Every great thought clearing the brain gives new re-creative force, puts new life into the very scum of things. Through intellect and affection, new life comes to fainting souls. Every new burst of emotion arouses the will, and it is through action alone that character arises. We change our lives by our wills. Our destinies are in our own hands. “What thou lovest thou bccomest.” Moral power has in it the life principle of re-creating. The worst consequences of sins are the breaking down of intellect and character. When one’s soul has come to sin, all the beauty of the present time is left behind. The great power is a loving power. But how docs one know it? Only through the touch of human love. You may talk to some who know not of love, but every soul forgives sins. The consequence of sin is distrust in other hearts.

Some one spoke to me of the fate of poor women who had sinned. I could not think how to help them. I was influenced by another’s sin. One of them came to me. At first I could say nothing, but my own soul helped me. Though our hearts hasten to Calvary, shall we pass by those who want us to help them?

I stood by a poor girl who was suffering for her own and another’s sin. I said, “God will forgive.” “Yes,” she answered, “God will forgive, but women won’t.” There are sins which can never be forgiven in this world or the world to come; but out of this loss come new hope and spiritual gain. They become monuments of love, faith, and trust in fellow men.

As I finished talking to her, they sent for me to go and see a man. I found him in a dark, gloomy corner of our beautiful city — a wreck, apparently. He had sown to the wind and was reaping the whirlwind, he had done what many young men are doing — he had “sown his wild oats.” He was what we should call a delicate man; used the vernacular which learned men use; he was a college man. “I got off the wrong way,” he said, “I want to know how to get hold of life anew. I can’t see a clear way.” He told me that all through these years his one true friend had been his little wife, and now for her sake he wanted to begin life again. I said: “My friend, I can’t help you to begin life anew. Reap what you have sown. There is no power in Heaven or on earth that can give you back these years. But God isn’t in a hurry; there is plenty of time. Take hold of that wife’s faith in you and it will help you. And in after years you will say you have gained much, you have been helped to carry character to a higher level. Remember this — the universe is before you waiting to raise the will of man when he is ready.” When I had finished I thought it would have been better to say, “Except ye become as a little child, ye cannot enter into the kingdom of heaven.”

The Balconies, from the High Peaks Trail, Pinnacles National Park.

(For what it’s worth, Pinnacles was filled with families with children this week; both the camp ground and the trails appear to be kid-friendly.)