Coloring pages are an essential part of how we make space for children in our Palo Alto congregation. When they enter of Main Hall, children and their parents can pick up packets of coloring pages and crayons, to give the children something to keep them engaged while they’re in the worship service.

Now, for years I’ve made special activity books for two of our intergenerational worship services, Easter and Flower Communion; the Easter activity books in particular are designed to have some educational value. But I haven’t put much thought into our regular weekly coloring pages; the Religious Education Assistant just found free coloring pages on the Web, and that’s what we used. The coloring pages may have nothing to do with our faith community, but at least the kids are happy.

But it occurred to me that we were missing an educational opportunity: why not come up with coloring pages that are both fun, and have some educational value? I did a Web search to see if other Unitarian Universalist congregations had produced coloring pages, and found the Alice the Chalice coloring pages by talented religious educator Rev. Amy Friedman — great stuff! But Amy has only provided a half a dozen different coloring pages. We give out packets with 8 or so coloring pages, and ideally I wanted to have a different packet for every month. It looked like I was going to have to make my own.

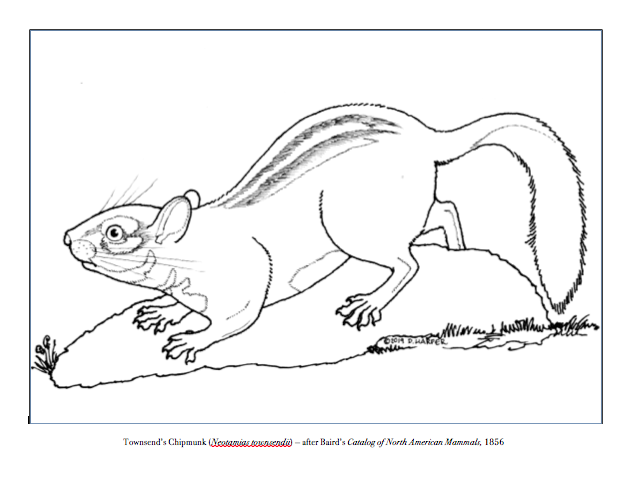

I began to collect images that I thought would be fun to color in. More importantly, I began to think about what I wanted to teach. Our religious education program does a lot with nature and ecojustice. So it made sense to produce coloring pages of living things; this would show young children and our families that we value non-human organisms, and if the images were of organisms native to California this would show our awareness of the immediate web of life surrounding us. (OK, maybe this is a little above the head of a four year old, but parents and older siblings will be looking at these, too.)

A search for public domain line drawings turned up a good selection of Pacific Coast wildflowers, as well as Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), and I was quickly able to assemble 8 coloring pages with California native plants, and 8 coloring pages with butterflies and moths. California mammals would be another obvious category, but I couldn’t find line drawings that would make good coloring pages; I was going to have to draw my own. I’ve started working on mammal coloring pages, and if you click on the image below you’ll get a PDF with two of those pages.

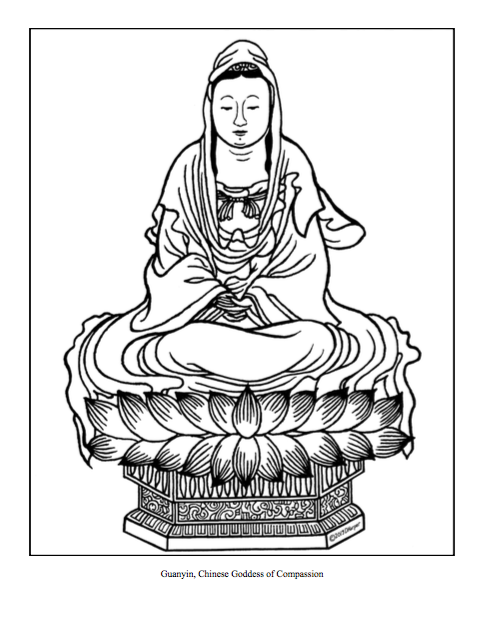

What about coloring pages with more explicitly religious content? We Unitarian Universalists are known for being feminists, so why not Goddesses Coloring Pages? I was able to find some public domain line drawings of goddesses, including goddesses from South Asia and the Mediterranean, and East Asia. I’m still looking for public domain images of goddesses from Indigenous America, Africa, and Oceania — and the images of the East Asian goddesses needed to be completely redrawn. Eventually, I’m planning on two packets of Goddesses Coloring Pages, and if you click on the image below you’ll get a PDF with two of those pages.

You’ll notice that I’ve put copyright notices on the coloring pages; I did so because it’s a big, bad Internet out there, and I don’t want other people to steal my work. But I hereby grant permission for Unitarian Universalist congregations, and other educational nonprofits, to print hard copies of these coloring pages for free distribution in their educational programs.

Eventually, I may put all my coloring pages on my curriculum web site, and if I do so I’ll mention it here on my blog. In the mean time, now you have 4 more coloring pages to add to the Alice the Chalice coloring pages.