The third installment of the Back in Time series:

Yet Another Unitarian Universalist

A postmodern heretic's spiritual journey.

The third installment of the Back in Time series:

I spent much of this week producing and aggregating online content suitable for UU kids. I’ve been trying to keep up with my sister, Abby, who’s been recording read-aloud videos at a breakneck pace — some of her videos have their own dedicated playlists at the UUCPA CYRE Youtube channel: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. I’ve been posting Beth’s Aesop’s Fables on another playlist. Yet another playlist has Amy reading aloud The Secret Garden.

And I had enough time left over to make another video in the “Things To Make” series, as well as adding another episode to the ongoing “Back in Time — to the Year 29!” saga.

It’s not easy to figure out how to make good online religious education content in the era of COVID. First and foremost, parents tell me that they don’t want another lesson plan; they’re sick of helping their kids do online school lessons, they don’t need another burden. So that means the videos I post have to require minimal supervision from an adult. Second, religious education is always optional, which means it has to be fun or engaging or no one will watch it.

These two constraints mean I have to interpret “religious education” pretty broadly. How is listening to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” religious education? Well, Unitarian Universalist religious education has always included the broad goal of supporting literacy; we want children to grow up thinking for themselves, and literacy promotes that in a number of ways. So while “Alice” doesn’t have any religious content per se, it’s a book that encourages literacy because it makes kids want to read.

And how is a series on “Things To Make” religious education? Well, the things I’m showing kids how to make promote independent play; they give kids a sense of agency; they cultivate creativity instead of consumption; and they have kids engage in hands-on embodied activities as a partial antidote to the disembodied lives many of us are now forced to lead online. This is rooted in good feminist theology: promoting embodied activities, promoting agency instead of passivity.

The “Back in Time” video saga could be considered religious education by almost any definition. (Yes, it would be considered rank heresy by many, but it’s still education on a blatantly religious topic.) The Aesop’s Fables series could certainly be considered moral education. But I think both showing kids how to make things, and reading aloud to kids, help us achieve some of the larger educational goals of Unitarian Universalist religious education.

Update, July 24: I’ve now added posts with links to the “Back in Time” series of videos on Youtube, as well as to subsequent video “Stories for All Ages.” The posts are backdated to the release date of the video, and include the full script for each video. You can see the entire series of posts here.

The second installment in the “Back in Time” series:

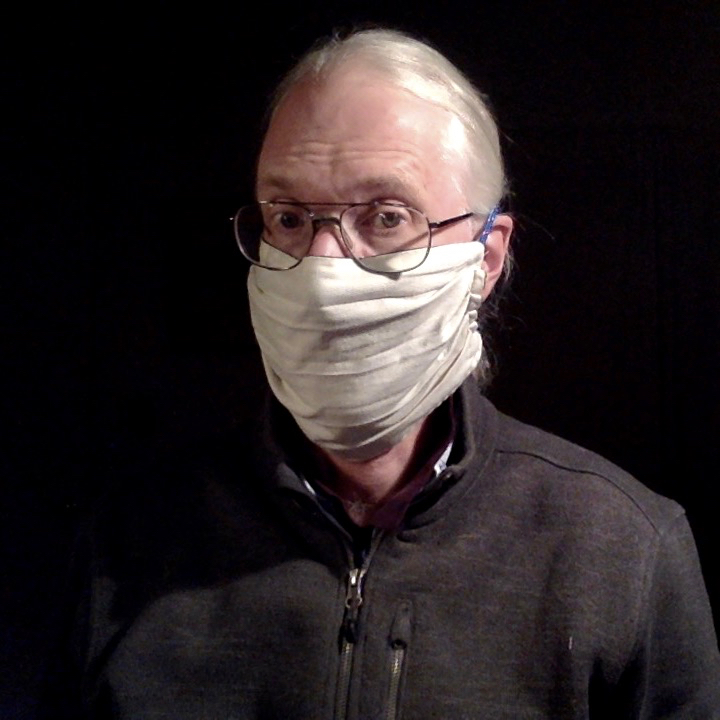

As of April 2, the San Mateo County Board of Health recommends that everyone wear a mask when they’re in public places.

I’ve been doubtful about the efficacy of masks, since my understanding is that wearing a mask won’t do much to protect you from being infected by others. But I’ve come to understand that masks might protect others from being infected by you, if you happen to have COVID-19 but are still asymptomatic.

So today I decided to be a good citizen and sew a couple of masks, one for Carol and one for me. I am very slow at sewing, partly because I don’t know how to use a sewing machine, and partly because I don’t know what I’m doing. But I found a good online video showing how to make one of the 2-layer pleated masks that are supposed to be the most effective handmade masks. I didn’t have the elastic bands called for in the video, but I had some 1/4 inch polyester cord to use for the ties. Carol has a big bolt of unbleached cotton muslin, and I sacrificed an old t-shirt. Sewing the pleats by hand was kind of a pain at first, but I quickly figured it out.

After two or three hours, I had a mask for Carol and a mask for me. We went to the grocery store, and three quarters of the people there were also wearing masks. Mask wearing peer pressure has begun.

As soon as we got home, I washed both masks in hot water, as you’re supposed to do.

Next step: make another mask for Carol using a high fashion fabric for the outer layer….

If you’re one of those using Zoom to carry out online programs and ministries for our congregations, you’ll want to update to the latest version of the Zoom app (a.k.a. the Zoom client). The latest version is 4.6.10, and I got notification about it an hour ago.

This update has one absolutely critical security feature that you must have: you can prevent participants from changing their screen name. The previous version gave participants the ability to change their screen name to anything, including something obscene, and the host couldn’t do anything except boot that person off the call.

There are other security enhancements, too. Update now.

My younger sister the children’s librarian has inspired me. Her library is closed, or course, so she’s creating online content by uploading an average of a new video every day to the Harvard (Mass.) Public Library Children’s Room Youtube channel. So far, she’s got a simple craft project, story time that parents can do with young children, and she’s reading aloud the entire Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

I like several things about Abby’s videos. First, they’re a great supplement to Zoom calls — some of us are getting Zoom burnout, and it’s nice to be able to watch a video when YOU want to watch it. Second, they’re Goldilocks videos — not too long, not too short, but just the right length. Third, they don’t put a big burden on parents — the crafts project can be done by kids on their own without parental supervision, kids can watch the installments of Alice on their own, and the story time for young children has them doing what they’re going to be doing anyway which is sitting in a parental lap.

So I repurposed this Youtube channel, where I already had some religious education videos. I added a video we used in last Sunday’s service. I created a couple of playlists, one for crafts (Abby’s craft video is included there), and another for story time (Abby’s Alice stories are going there, because Alice in Wonderland is a sacred text). I’ve got a children’s librarian from our congregation half convinced to do a story time, I’m planning a story time (I think I’ll read aloud from an old edition of the Jataka Tales), there will be more crafts projects.

Blog readers, if you know of some videos that you think would be appropriate to share on this Youtube channel, please send me the links. I can’t promise to put everything up, but I’d really like to see your suggestions — send them to danharper then the little “at” sign then uucpa then a dot then org.

The first installment of the “Back in Time” series….

This Sunday, during our congregation’s online service, we’re going to go back in time…

…to the year 29 C.E., to a small town in the land of Judea. There we will meet a fellow named Ishmael, who’s the kind of person who loves to spread rumors.

If Ishamael lived today, he’d be the kind of fellow who emails you the latest internet conspiracy theory. But since he lives in the year 29 in Judea, he spreads his rumors face-to-face in the town’s marketplace. He meets up with a woman named Martha. When he learns that Martha’s brother Peter has joined the entourage of the famous rabbi Jesus of Nazareth, not surprisingly he has a few conspiracy-theory-type rumors to tell Martha. This causes Martha to wonder if her brother is going to be OK….

Our trip to the past will take less than three minutes, allowing us plenty of time for the usual singing, music, preaching, etc. The whole thing will be livestreamed on the Facebook page of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, this Sunday at 9:30 and 11.

While we have to shelter in place, I thought I’d have time to turn to serious reading. There’s a pile of books on the floor next to my desk with titles like How Judaism Became a Religion: An Introduction to Modern Jewish Thought, and Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, and Capital and Ideology.

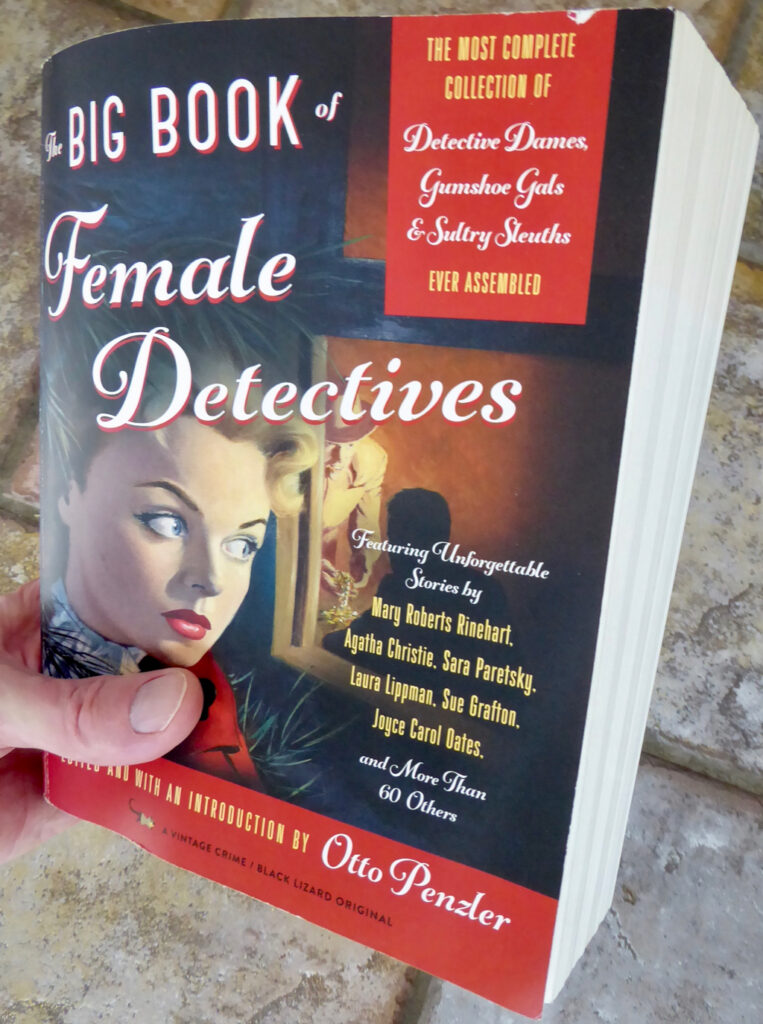

And what have I actually been reading? Very little in the way of serious books, I can assure you. It turns out that I’m actually the teensiest bit stressed out, between the COVID-19 pandemic, and working way too many hours to get our congregation’s programs and services online, and having my usual routine completely disrupted. Without diminishing the importance of the first two, I suspect this last may have had the biggest effect on me: I thought I wasn’t much of a creature of habit, but like all humans I’m very much a creature of habit, and when my daily habits are so completely changed it’s unsettling. So I’ve been reading fluff, junk, pulp fiction — in short, guilty pleasures.

I’ve been reading The Big Book of Female Detectives, ed. Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime, 2018). It’s 1,111 pages of guilty pleasures, stories with no intellectual value at all. All right, I admit that there is one piece of serious literature in the book, a very short story (four pages) by Joyce Carol Oates, which I skipped over because every paragraph began with the word “because” and that required a little too much thought on my part. So subtract four pages, and make that 1,107 pages of pure unadulterated thoughtless fun.

The first dozen stories are British and American stories from before the First World War; many of the plots creak alarmingly under the weight of suspended disbelief. One of my favorites from this section of the book is “An Intangible Clew” by Anna Katharine Green, featuring Violet Strange, a very wealthy young woman who is secretly a brilliant detective. Here is how she arrives at the scene of the crime in this story:

“When the superb limousine of Peter Strange [Violet’s brother] stopped before the little house in Seventeenth Street, it cause a veritable sensation…. Though dressed in her plainest suit, Violet Strange looked much too fashionable and far too young and thoughtless to be observed, without emotion, entering a scene of hideous and brutal crime…. Her entrance was a coup du theatre. She had lifted her veil in crossing the sidewalk and her interesting features and general air of timidity were very fetching….”

Many of the early stories in the book — the stories are arranged in chronological order — feature female detectives who hide their brilliance under an appearance of brainlessness. Thus when you finally get to Agatha Christie’s novel The Secret Adversary, featuring Tuppence Cowley as detective, with her sidekick Tommy Beresford, you realize how innovative Christie was. Tuppence Cowley is smart, funny, and brave. She doesn’t pretend to be stupid when she’s not (indeed, it’s Tommy who isn’t very bright, and admits it), and she comes across as a real person, a three-dimensional character. The plot of The Secret Adversary whizzes along at a breakneck pace, so fast that the unbelievable parts of the plot (of which there are a great many) have gone by before you realize how unbelievable they are. And who cares about the plot anyway? — you read this book to enjoy Tuppence’s personality.

Worthy of note is a mid-twentieth century story by Mary Roberts Rinehart, once a best-selling author and now mostly forgotten. Rinehart’s “Locked Doors,” which has appeared in other anthologies, is less a mystery story than a story of suspense; but there’s a surprise ending to the story that makes perfect sense of all the outre plot elements, and while it’s not entirely believable, the ending is believable enough to make it satisfying.

The next high point in the book is a story by Sue Grafton, featuring her famous detective Kinsey Milhone. It’s easy to forget how revolutionary Sue Grafton was: not only are her stories reasonably well-written, but Kinsey Milhone is as smart, funny, and brave as is Tuppence Cowley, but Kinsey doesn’t need a man to make her complete — she doesn’t need to get married (Tuppence agrees to marry Tommy at the end of The Secret Adversary), she doesn’t need a male boss (Tuppence reports to the powerful and mysterious Mr. Carter), she’s independent and alone and likes it that way. If Kinsey Millhone is a result of the feminist revolution of the 1970s, then thank God for the feminist revolution of the 1970s.

Most of the other stories in the book have no redeeming value, but they’re so much fun to read — even if you forget them moments after you’ve finished them. These stories would make perfect beach reading, but since we’re not allowed to travel to the beach they also make perfect shelter-in-place reading, requiring no intellectual effort while keeping your mind off of current events.

While livestreaming the Sunday service, I happened to catch sight of a couple of Western Bluebirds. After the service was over, I went out to the front garden for a little stress reduction break, and sure enough, there was a bluebird resting on the perch attached to the nesting boxes.

Thanks to my super-zoom pocket camera, I managed to get a pretty good photo of this bird:

We had bluebirds nesting in these boxes from 2016 to 2018. The nesting boxes began to split in the sun, so we had to replace them in early 2019; nothing nested in the boxes last year. I’m hoping that this bird has decided this will be its nesting site in 2020.