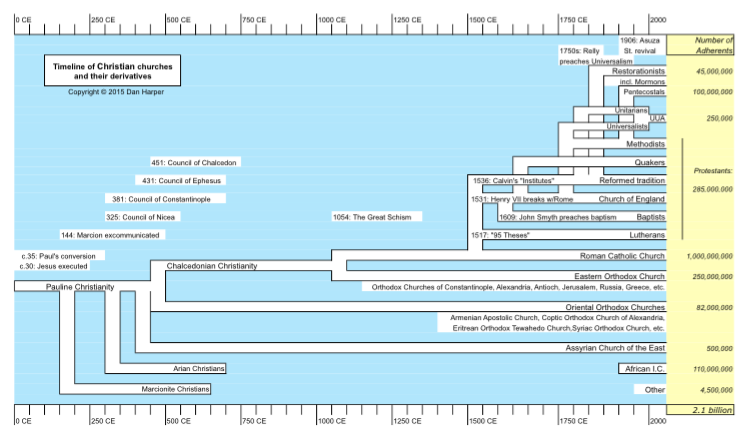

Another handout I developed for our “Neighboring Faith Communities” course for middle schoolers, a timeline of Christian churches and their derivatives:

Christian church timeline (PDF)

This is a revision of an earlier version of this timeline, which I originally posted here.

One purpose of this chart is to introduce middle schoolers to the incredible diversity of Christian churches, especially churches that are not well know in the West (i.e., Oriental Orthodox Churches, African Independent Churches), and groups that are often passed over or ignored by religious liberals (i.e., Restorationist groups including Mormons, Pentecostals).

Another purpose of the chart is to show how Unitarian Universalists do in fact derive from Christian churches — and further to show how very few in number we Unitarian Universalists are compared to the various Christian churches.

Chart edited. See comments.

No baptists? Either the British baptists (ancestors of the Southern Baptists) or the middle European Anabaptists. Also do Quakers who do not have either baptism or eucharist really fall into the Protestant camp?

Erp: Oops. Chart edited to include Baptists. New version now up.

Re: Quakers: The scholars I have consulted consider Quakers to be part of the Radical Reformation, and therefore Protestants.

Curious: where do the Amish fit in?

(And your middle-schoolers ought to do a field trip to the Midwest. We have a lot of interesting faith communities out here, some VERY interesting…)

I see we have the British baptists but not the continental Anabaptist tradition that led to the Amish, Mennonites, and related groups (if I recall my history). Perhaps too small. Within the US one might also want to consider AME and AME Zion and the other churches that formed because of segregation in the parent denomination.

One reason I mentioned Quakers is because legally they were treated separately in English law (among other things after the marriage act of 1753 and until the 1830s all legal weddings had to take place under the auspices of the Church of England including those of Baptists, Unitarians, and Catholics; the sole exceptions were Jewish and Quaker weddings).

I wonder what would happen if one gave the middle schoolers a long list of denominations, have each pick one (no overlap), do research, and then give a quick report to the class.

Jean and Erp, you both mention the Amish, which can be put into the Continental Anabaptist tradition — which is different than the English Baptist tradition — and in fact there really isn’t just one Continental Anabaptist tradition. The Continental Anabaptist tradition is part of the Radical Reformation, and my understanding of the Radical Reformation is that there never were neat and tidy divisions between the different religious groups. George Hunston Williams’s definitive book on the topic runs to some 1500 pages, and if you try to read that book you will I think be staggered by the fluidity and complexity of the Radical Reformation. It simply cannot be reduced to a simplistic chart like the one above.

This is a good thing to remember: this chart really does not reflect reality all that well.

Erp, nearly all the major Protestant denominations split over the race issue in the 19th C., and many of them have split (and continue to split) over other issues as well. The Presbyterians are currently splitting over the issue of same sex marriage, and a number of their churches are seceding to form ECO Coventntal-something-or-other. The Episcopalians are currently splitting around the same issue, with a few of their churches leaving the U.S. Episcopal Church to affiliate with African Anglican churches that oppose same sex marriage. The boundaries of Protestant churches are continually moving and shifting. Nor are the Orthodox churches immune — when the nations of Eritrea and Ethiopia split, so did they Ehtipopian Orthodox Church. And the Roman Catholics have split too, with various splinter Catholic groups forming in the U.S. There is simply no way to show all these splits and schisms in a chart this size.

The real point for this chart is to provide the roughest of outlines to show where the various churches stand in relation to each other. However, the course that this is going to be used in is not much concerned with the doctrinal/philosophical dimensions of religion, nor with the legal/ethical dimension of religion (using Ninian Smart’s seven dimensions of religion as a guide). Instead the course focuses on three other dimensions of religion: the material/artistic dimension, the experiential/emotional dimension, and to a certain extent the social/organizational dimension.

Protestant Churches in the US split over race. I’m not sure they did in other parts of the world (except possibly for South Africa and that was more mid-20th century). I agree that churches split/merge/resplit in all sorts of odd ways so a simple tree diagram does not work.

And what about the 23 Eastern Catholic Churches which are in full communion with Rome but are decidedly not Roman Catholic.

Sally M, the point of the chart is not to map all of Christian diversity (impossible on such a small chart!). But the chart can show a little of how Christianity has grown increasingly diverse over the past two thousand years.