(Continuing with yesterday’s Memorial Day post.)

Briton Nichols, a Life of Adventure

[PLEASE NOTE: In this post, I draw a connection between Briton Hammon of Marshfield and Briton Nichols of Hingham/Cohasset. I based this conclusion on Robert Desrochers’s essay “‘Surprizing Deliverance’?: Slavery and Freedom, Language, and Identity in the Narrative of Briton Hammon, ‘A Negro Man,’” in Philip Gould and Vincent Carretta, eds., Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic (Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2021), p. 168-169. (I did not cite Desrochers in the original post, and I apologize for my inadequate footnotes.) However, in this comment local historian Ellen S. Miller cites documentary evidence that these are two entirely different people. I’m going to leave the post as originally written (I don’t want to hide my mistakes), but I’m injecting subtitles and notes to make it clear that documentary evidence does not support the conclusion that the two are the same person. More on Ellen S Miller.]

The second story of a Revolutionary War veteran is especially interesting because of the way historians have been able to connect separated facts in the historical record, and then tell a fuller story of one person. This is the story of Briton Nichols.

In the historical record, you can find a list dating from July 19, 1780, giving the names of nine men from Cohasset who began six month’s military service on that day.(10) One name on that list, the name of Briton Nichols, stands out for two reasons. First, he had a very unusual name; the written record shows no other man in Massachusetts with the first name of Briton. Second, Briton Nichols is identified as being Black, the only person on that list whose race is given, and (as near as I can tell) the only Black man from Cohasset who served in the American Revolution.

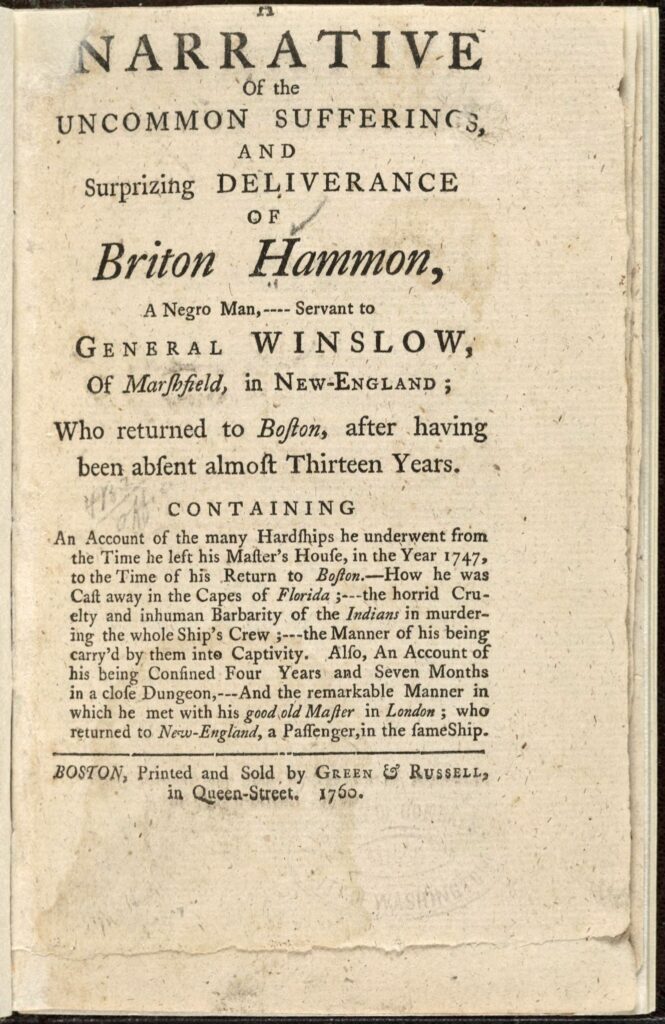

Because Briton Nichols had such an unusual first name, and because his race is given, historians have been able to trace his life in more detail.(11) Historians discovered that in 1760, he published a book in which he told of thirteen years worth of adventures.(12)

[N.B.: as noted above, the two are not the same person; therefore I’m inserting a subtitle here to show that the following is about Briton Hammon.]

Briton Hammon (Who Is Not Briton Nichols)

As a boy, he was enslaved by the Winslow family of Marshfield. At that time, he called himself Briton Hammond. On December 25, 1747, with the permission of his master, Briton left Marshfield to go on a sea voyage; perhaps his master hired him out as a sailor, taking a cut of his salary, a common practice in those days. Briton doesn’t say how old he was when he sailed, but later sources give his birth year as roughly 1740, so he may have been a boy or a young teen. The ship Briton was on sailed for Jamaica, took on a cargo of wood, and sailed north. Having struck a reef off Florida, the ship was attacked by Native Americans who killed everyone except Briton, and then set the ship on fire. After being held captive by the Native Americans for five week, he was able to make his escape on a Spanish schooner, whose captain recognized him, and took him to Havana, Cuba. The Native Americans followed and demanded the Governor of Havana return Briton to them, but the Governor paid ten dollars for him and kept him. A year later, Briton was caught by a press gang, but he refused to serve in the Spanish navy and was thrown in a dungeon.

Briton was finally released from the dungeon four years later, though he was still trapped in Havana. Then a year after his release from the dungeon, he managed to escape from Havana aboard a ship of the British Navy. It appears Briton served in the British Navy for some time thereafter, aboard several different ships, until 1759 when he was wounded in the head by small shot during a fight with a French ship. Briton was put in Greenwich Hospital, where he recovered from his wounds. After additional service on British Navy ships, this time as a cook, he managed to find a berth on a ship bound for New England. By coincidence, his old master, one General Nichols, was on the same ship. Through that chance meeting, Briton was finally able to return to his home in Marshfield after a thirteen year absence.

Soon after his return from Marshfield, Briton’s account of his adventures was published in Boston, perhaps the earliest published memoir written by an African American. Two years later, in 1762, Briton married Hannah, a Black woman who was a member of First Church in Plymouth (today this a Unitarian Universalist congregation). In the late 1770s, Briton left the Winslow family, possibly upon the death of his master, and moved to Cohasset to join the Nichols family; at this time he changed his last name from Hammond to Nichols.

[N.B.: At this point, I made a connection between Briton Hammon, who wrote the Narrative, and Briton Nichols of Hingham/Cohasset. As noted in the introduction, I based this on an essay by Robert Desroches. However, local historian Ellen S. Miller says this: “Nathaniel Nichols Sr. of Cohasset had an enslaved manservant Briton whom he bequeathed to his son Nathaniel in 1757, three years before Briton Hammon’s return. Both of the Nichols men died by the time the estate was settled in 1758. At the same time Nichols bequeathed Phebe, an enslaved servant whom Briton Nichols would later marry, to two of his daughters.” Thus, the documentary evidence from local archives does not support Desroches’s contention that Briton Hammon is the same person as Briton Nichols. However, Briton Nichols’s story is interesting enough by itself to remain here. Just remember that the documentary evidence does not support the conclusion that he’s the same person as Briton Hammon. Therefore, here’s another subtitle to clarify that this is a different person.]

Briton Nichols (Who Is Not Briton Hammon)

In 1777, Briton joined the Continental Army.(13) He must have been around forty years old when he enlisted. We can only speculate as to why he decided to enlist at that age. Most likely, enlisting in the military was a way for him to free himself from slavery. Ambrose Bates, who was one of Briton’s messmates, left a diary that tells a little about their military service.(14) Briton Nichols, Bates, and the rest of their contingent left Cohasset on August 27, 1777, and finally reached Saratoga, New York, in early September. There they joined the conflict between the Continental forces and General Burgoyne’s forces. Much of their military service was filled with boredom. Several days were filled with monotonous marching back and forth from one place to another. On other days, Bates simply records, “Nothing new today.” Those days of boredom were interspersed with days where they had more than enough excitement. To give just one example, on October 7, Bates recorded: “today we had a fight we were alarmed about noon and the fight begun, the sun two hours high at night and we drove them and took field pieces and took sum prisners.” The tide of battle was with the Continental forces, and Burgoyne finally surrendered on October 16. Soon thereafter, Bates and the other Cohasset men marched down to Tarrytown. Their service in Tarrytown was less exciting. Finally, on November 30 their term of military service ended, and they began marching home. They finally arrived back in Cohasset on December 7. So ended Briton Nichol’s first term of military service.

Briton Nichols enlisted again in 1780, giving his age at the time as forty years old.(15) I suspect he lied about his age, presenting himself as younger than he was. I could find no details of his 1780 military service. The next time I found him in the historical record was in the 1790 federal census. At that time, he was living in Hingham as a free Black man, along with his second wife Experience and one other household member, probably their child.

The story of Briton Nichols shows how we can recover some of the lost knowledge of Revolutionary War veterans. Briton Nichols was little more than a name on a list of soldiers, until historians were able to deduce that he was almost certainly the same person as Briton Hammond who had had such amazing adventures from 1747 to 1760.

Of special interest to those of us who are currently part of First Parish, Briton Nichols would have attended Sunday services right in our historica Meetinghouse. We can imagine him sitting upstairs in the balcony, where people of color and White indentured servants had to sit. We can imagine Briton sitting in that gallery on Sunday, August 24, 1777, a few days before he marched off to Saratoga. We can imagine the prayers of the entire congregation centering on the hope that all nine of the Cohasset men marching off as soldiers that week would return home safe and sound.

We today think of all those from this congregation who have served in the military. We think of all those veterans who are now members and friends of First Parish. We also think of those who grew up in this congregation and went off to join the armed services. And we think of those people from First Parish who died in military service. It is good for us to keep alive the memories of all those who served in our armed forces. It is good to keep those memories alive, because it reminds us of the bonds of love which transcend even death.

Tomorrow: a follow-up post.

Notes

(10) Victor Bigelow, Narrative History of Cohasset (1898), p. 308.

(11) An introduction to a narrative by Briton Nichols, who earlier in life was called Briton Hammond, gives an overview of what historians conclude about his life: “It is accepted that in 1762 Hammon married Hannah, an African American woman and member of Plymouth’s First Church, with whom he had one child. For many years this was all that was known of Hammon’s life after his return to New England. More recent research, however, has revealed that Hammon probably changed his name to Nichols some time in the late 1770s, after the family with whom he and his master were living when Winslow died in 1774. Briton Nichols is listed as having fought for the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War, as did many members of the white Nichols family…. In later census records, Briton Nichols is described as a free husband and father.” Derrick R. Spires, editor, Only by Experience: An Anthology of Slave Narratives (Broadview Press, 2023), p. 54.

[***As noted above, I neglected to include a citation here for Robert Desrochers, “‘Surprizing Deliverance’?: Slavery and Freedom, Language, and Identity in the Narrative of Briton Hammon, ‘A Negro Man,’” in Philip Gould and Vincent Carretta, eds., Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic (Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2021), p. 168-169. Please note that the documentary evidence cited by Ellen Miller does not support Desrochers’s conclusions. And to be fair, Desrochers presents his conclusions as tentative. Here is the relevant passage in Desrochers’s essay:

[“During the American Revolution a ‘negro’ named Briton Nichols enlisted at the rank of private at least four times between August 1777 and July 1780 for short stints in Massachusetts regiments out of Hingham and neighboring Cohasset. Nichols appears in the print record again in the federal census of 1790, according to which he was a free black, head of a household of three in Hingham, and also the only identifiably non-white man in the entire state with the forename ‘Briton,’ variously spelled. There is reason to believe that Briton Nichols of Hingham, Massachusetts, was in fact the man of shifting identities formerly known as Briton Hammon. When ‘good old Master’ Winslow died in April 1774 he resided at Hingham with his sister Bethia and her husband, Roger Nichols. At this point we can only speculate that sometime after Winslow’s death Hammon became tied to the family of his old master’s brother-in-law, relocated to Hingham, and adopted the Nichols surname to announce the change and perhaps a shift in his patriotic loyalties….

[“Other clues point to the common identity of Briton Nichols and Briton Hammon, and suggest that in some ways black freedom remained no less conditional at the end of the eighteenth century than it had been in the middle. The name of a white soman identified only as ‘Mrs. Hammon’ appeared in the Hingham census return just two lines above the aforementioned record for Briton Nichols. Was this Mrs. Hammon of the same family from which Briton Hammon’s surname derived? Since the pages of data compiled by the census takers on a door-to-door basis would resemble neighborhood grids if plotted on a map, we can presume that Briton Nichols and Mrs. hammon lived close to and knew one another. One wonders on what terms. Did Nichols not live near but actually with Mrs. Hammon, like the one in three ex-slaves in post-revolutionary Massachusetts who resided in a white household? In short, was Briton Hammon’s brief Narrative not the finished account of a black prodigal after all, but a chapter in an unfinished book of a pilgrim’s progress towards freedom? We are left for now with as many questions as answers. Perhaps it is only fitting, however, that Briton Hammon continues to elude us, nearly two-and-a-half centuries after his first and apparently only appearance on the public stage.”]

(12) In this paragraph, the details of the earlier life of Briton Nichols/Hammond are taken from his book, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760); as reprinted on the Pennsylvanian State Univ. website https://psu.pb.unizin.org/opentransatlanticlit/chapter/__unknown__-9/ accessed 22 May 2025.

(13) Victor Bigelow, p. 208.

(14) Victor Bigelow reprints the text of this brief diary, pp. 299-303.

(15) Entry for Briton Nichols, 19 July 1780, “Massachusetts, Revolutionary War, Index Cards to Muster Rolls, 1775-1783,” FamilySearch.org website https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QLLS-BBT3 accessed 22 May 2025.