Another in a long-running series of brief biographies of obscure Unitarian Universalists. This is a chapter from my long-delayed book on Unitarians in Palo Alto from 1895 to 1934.

Out of poverty

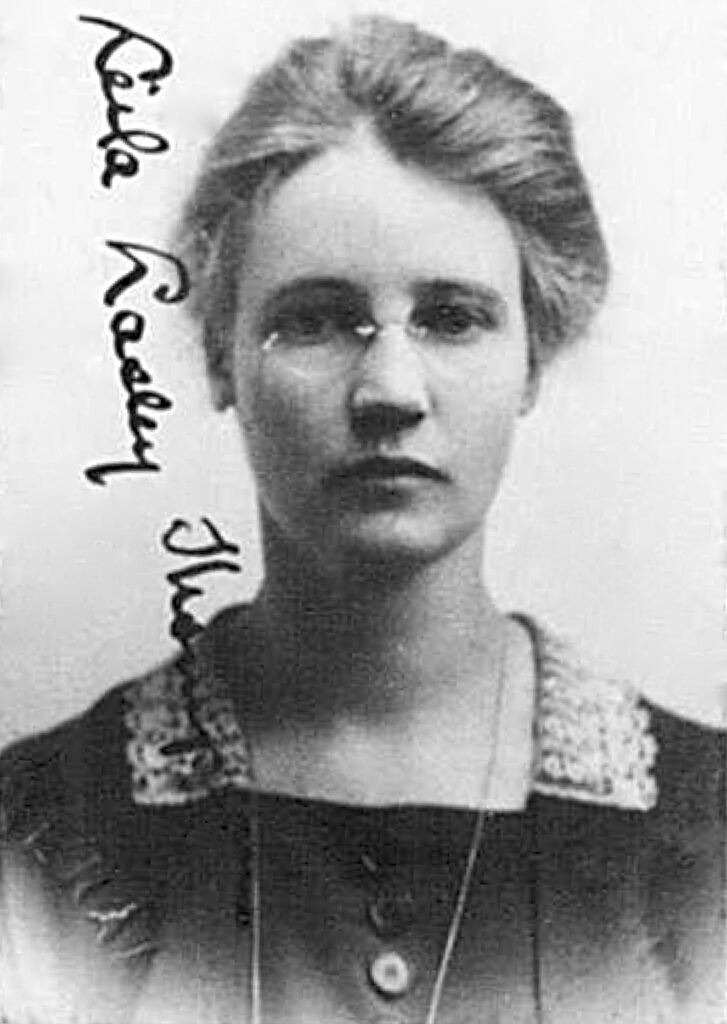

Assistant minister, then settled minister, of the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto in 1926-1927, she was born at Larned, Kansas, on October 18, 1888, the first child of Fred Newton Lasley and Leura Auretta Davis. Times were hard in Kansas, and not long after Leila was born, Fred scraped together enough money to take the train to Portland, Oregon, where his brother and half-sister lived, in hopes of finding work. He found work as a carpenter, and saved enough money to send to Leura so that she could join him in Portland. Leura was just twenty years old when she took that five day journey by rail, carrying a baby in diapers, and with no one to help her.

After a year in Portland, Fred found work managing a farm in Springdale, east of Portland. He and Leura felt financially secure enough to have more children, and Leila’s younger sisters Weltha Evadna Lasley, and Gladys Mable Lasley, were born in Springdale; a brother Clarence, born in 1890, died young. By 1896, when Leila was 8 years old, the family had saved enough money to purchase their own farm in what is now Corbett, Ore. On the side of a hill, Fred built a two room shack using rough lumber he purchased, with a root cellar underneath. Fred built a trough that ran from a nearby spring to the house, so that they would have running water in the house. Leila’s sister Clara Belle Lasley was born on the farm the next year, in 1897. Leila’s younger brother Walter was born there in 1905.

The Lasleys were “poor as church mice.” They had few toys, and their clothes were often faded and patched. But their mother kept them looking neat and tidy, and encouraged them with homey moral sayings. If the children felt discouraged and unable to do something, their mother would say, “Mr. Can’t just fell off the fence and broke his neck — now you girls get back to work.” If their mother heard something that sounded like gossip, she would say, “That doesn’t concern you, so don’t publish it.” What Leura lacked in schooling, she made up for in common sense. Leura also had pride: she wanted her daughters “to be brought up decent.”

Leila was not able to complete high school in Corbett. By the time she was 19, the age at which her mother had married, Leila had left her parents’ home to live by herself in the city of Portland, finding work as a domestic servant. It’s not clear why Leila went to Portland: perhaps in 1907 there was no high school yet in Corbett; perhaps her family needed her to find a job so she could send money home; perhaps she wanted to escape rural poverty. In any case, after two or three years working as a domestic servant, in 1910, at age 21, she returned to high school, attending Washington High School in Portland, and boarding with the family of a bank cashier on East 24th Street. She told the 1910 U.S. Census that she was only 18 years old, a reasonable age for a high school junior, so perhaps she was trying to hide the fact that she was older than most high school students. The next year, in 1911, she graduated from Washington High School, Portland.

One of her poems was published in the high school yearbook. Even though it isn’t a particularly noteworthy poem, it’s worth quoting in full. First, since so little of her writing has survived, this is an opportunity to hear her speak in her own words. Second, the poem may express something of the trials she experienced as an intellectually talented woman growing up in rural poverty. Finally, the poem expresses a life philosophy that would have helped Leila later in her life when she confronted tragedy and duplicitousness:

I held in my hand a broken stemmed rose,

Whose petals were crushed and foliage torn.

It had lain on the ground ‘mid the pebbles and dust

Since carelessly dropped there by someone that morn.

Its freshness was withered, its colors despoiled

And its uncompassed beauty would smile forth no more;

Yet still though its form was broken and crushed,

It shed forth its fragrance as sweet as before.

As I tenderly gazed on the fair dying flower,

And drank in its fragrance so sweet so pure,

There came to my soul a message from Heaven

Bearing courage and comfort my grief to endure.

“Though your burden be great and the way steep and long,

’Twill not help to be sad and to grieve all the day.

But be brave, and be kind; wear a smile, breathe a song;

And you’ll gladden your own and a lone brother’s way.”

College, marriage, and war

The autumn after she graduated from high school, Leila entered the University of California at Berkeley. The university gave her a scholarship, and she started out studying natural science. In 1912, while she was at college, her younger brother Edward was born. By 1913, Leila had changed her area of study to the social sciences, and in 1915 she received her A.B. in philosophy from the University of California. After graduation, she taught high school in Toledo, Oregon, for four years, becoming the principal of the high school after one year. She also pursued graduate studies, returning to Berkeley in the summers of 1916 and 1917. In the fall of 1917, she left the Toledo, Ore., high school, and became the principal of the high school in Corbett, Ore., moving back to the town where her parents and her siblings still lived.

Beyond the pleasure she took in studying, another attraction of traveling to Berkeley in the summers was a young Unitarian named Charles Henry Thompson. Charles and Leila had met while students at the University of California, and Charles was living in Oakland practicing law. After a long-distance courtship, Leila and Charles finally married in 1918, and the Pacific Unitarian reported:

“On June 1st, at the Church of Our Father, Portland, Oregon [now called First Unitarian Church], by Rev. W[alter] G[reenleaf] Eliot, Jr., Sergeant Chas. H. Thompson, Jr., was married to Miss Leila Lasley. Sergeant Thompson is with Company M, 3rd Infantry, Camp Lewis, Washington. Before enlisting shortly after the outbreak of war, Sergeant Thompson was one of the most loyal and enthusiastic members of the church in Berkeley and filled many offices in church, school, and Channing Club [i.e., college group]. At the time of his enlistment he was senior usher, a teacher in the church school, a director for the Pacific Coast of the Y.P.R.U., and secretary of the Laymen’s League of the Church. He had formerly been president of the Channing Club. Mr. Thompson has been greatly missed by his many friends but they rejoice in his good service to his country and they are now congratulating him upon his marriage to Miss Lasley, who was active in the Channing Club while a student at the University of California.” [Pacific Unitarian, Aug., 1918, p. 192]

One unresolved question is whether Leila became a Unitarian while in college in Berkeley, or while living in Portland in her late teens. Leila was probably not a Unitarian as a child, since there was no Unitarian church in Corbett, and there’s no evidence that her parents or siblings were ever Unitarians. Whenever she first became a Unitarian, it’s certain that she was a Unitarian by the time of her marriage.

Leila and Charles lived in Tacoma for the summer after their marriage. Then Charles was sent overseas, and Leila returned to Corbett to work as the high school principal. But in late October or early November, Leila learned that Charles had been killed in action during the Battle of Argonne, on September 27, 1918. He was buried in France.

Unitarian ministry

Leila moved to Berkeley not long after Charles’s death, and began living with her mother-in-law Bathsheba (or “Basha”) Thompson. The two of them must have been drawn together by their shared grief over the death of Charles, but they also liked one another enough to continue living together until Basha’s death. In 1920, they were living together in Berkeley, where Leila taught high school, and Basha worked as a private tutor.

Leila continued to further her teaching career. She did additional graduate work at the University of California at Berkeley in the summer of 1920, and received her California high school teaching certificate from the University in that year. She also continued her involvement with Unitarianism, serving from 1920 to 1922 as the Pacific Coast Secretary for the Young People’s Religious Union, or Y.P.R.U., which was then the Unitarian organization for people in their late teens and twenties. As she thought about her career, she began to feel that she wanted to do more with Unitarianism.

In September, 1922, Leila traveled with Basha to England to study religion. She enrolled at Manchester College, Oxford, a Unitarian theological school in England. She received a certificate from Manchester College in 1924, and in June of that year she was received into the fellowship of Unitarian ministry of Great Britain. In a letter recommending her to the American Unitarian Association (A.U.A.), it was noted that she did “splendid work” for Unitarianism wherever she went in England.

During the following year, Leila and Basha traveled in Europe. We have to imagine that they visited both the battlefield in France where Charles was killed, and the cemetery where he was buried. The two of them returned to the United States in May, 1925, in time to attend the Centenary meetings of the A.U.A. in Boston.

From Boston, they returned to California. Leila spent a year at Pacific School for the Ministry (now Starr King School for the Ministry), studying ancient Greek. She received her Probationary Fellowship Certificate from the A.U.A. in the spring of 1925. She was now 36 years old, a second-career minister, a mature woman, and by all indications someone of superior intellect and excellent moral character.

In the 1920s, the leadership of the A.U.A. in Boston — all of whom were men — became increasingly resistant to recommending women ministers to Unitarian congregations. On the West Coast, however, far from Boston, Leila was hired in 1925 by the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, to serve as assistant for Rev. Elmo Arnold Robinson while he took a sabbatical to study at Harvard University. She began serving in January, 1926, and the church ordained her on February 7, 1926.

Her ordination involved some Unitarian luminaries. Rev. Dr. William Wallace Fenn of Harvard University preached the sermon. Rev. Dr. Earl Morse Wilbur of the Pacific School of Religion gave the ordination prayer. Rev. Carl B. Wetherell, the A.U.A. Field Secretary for the West Coast, brought the greetings from other congregations. Rev. Clarence Reed, former minister of the Palo Alto church, now the minister of the prestigious Oakland Unitarian church extended the right hand of fellowship to Leila. None of these men, of course, worked directly for the A.U.A. in Boston; even Wetherell, though he was a Field Secretary for the A.U.A., had a certain amount of independence from the Boston headquarters.

Leila was granted final fellowship as a Unitarian minister in March, 1926. By April, 1926, Elmo Robinson had decided not to return to the church. After his resignation, the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto voted to call Leila as their next minister, thus becoming the first congregation in Palo Alto to call a regularly ordained woman as minister.

However, the church was not thriving. In his final annual report to the church, Robinson had noted that attendance at Sunday morning worship services averaged between 30 and 40 people; sometimes attendance at the Sunday school was greater than attendance in the worship service. Attendance continued to decline after Robinson’s resignation. It may be that a female minister was too much of a novelty, even for a relatively progressive college town. Nor was it a congregation where a brand-new minister was likely to succeed, no matter what gender: still dependent on aid from the A.U.A., still with simmering resentments from a bitter internal conflict during and after the First World War, and with several of its strongest lay leaders dead or getting older, the congregation would have been a challenge for a minister with many years of experience. Indeed, Leila’s status as a war widow may even have unwittingly antagonized some of the pacifists in the congregation.

It soon became clear to Leila and the lay leaders that the church’s finances didn’t allow her to continue as a full-time minister. After serving the congregation for two years, Leila resigned. The church never called another minister. They struggled along with part-time student minister for a year, then turned the building over to the A.U.A. to use as a teaching church for a (male) student minister. Leila was their last full-time, called, ordained minister.

Although most of the church’s records from 1926 and 1927 are no longer extant, the fragmentary records that do remain seem to indicate that Leila did not bear primary responsibility for the failure of the church. She had a great deal of experience with what would now be called young adult ministry, and the church’s college group remained strong through 1926 and 1927. On the other hand, Leila lacked Elmo Robinson’s deep experience in religious education, and it is true that the Sunday school enrollment slowly declined while she was minister. Yet she was also willing to learn and to experiment, and with the approval of lay leaders she tried holding services on Sunday evening to see if that would boost attendance (it didn’t). In addition, there is some evidence that her ministerial colleagues in Palo Alto thought highly of her. Leila did what she could with a hopeless situation, and she deserves credit for providing excellent ministry under difficult conditions. But the ultimate responsibility for the failure of the church lay elsewhere.

After resigning from the Palo Alto church, Leila returned to the University of California at Berkeley for additional graduate study, receiving her A.M. in 1929. She gave up on ministry — not surprising, given the animosity the A.U.A. displayed towards women ministers in those years — and returned to teaching. After such initial promise, she would never serve another Unitarian church.

In June, 1931, the Fellowship Committee of the A.U.A. wrote to Leila to say they had noticed that she had not served a congregation as a minister since 1928. “We like to keep our list as active as possible but we have no wish to be drastic,” the letter went on, disingenuously, and then asked if she intended to continue as a minister. If she did not intend to continue, they would like to remove her from their list of ministers. Despite the vaguely hostile tone of this letter, Leila wrote a measured letter in response saying that she didn’t think it likely that she would return to active ministry, and politely requested removal from the fellowship list. During the Depression, the A.U.A. defined “minister” narrowly, as an ordained person serving in a congregation. (Elmo Robinson would also be removed from Unitarian fellowship in these years, because rather than working in a congregation he was teaching at San Jose State University.) Removing such ministers from fellowship was a foolish policy on the part of the A.U.A., but it was another half century before the denomination came to understand the power of what are now called community ministers. We can only speculate how Leila Thompson might have contributed to the Unitarian movement as a community minister.

Denied by the AUA

Leila continued to teach, and continued to live with Basha, who was now 77 years old. The two of them went to Europe again in the summer of 1932. They were still sharing a home when Basha died on March 25, 1936, at age 80.

Less than a year after Basha’s death, in the spring of 1937, Leila dipped her toe into city politics. She ran for Berkeley City Council, but came in a distant sixth out of eight candidates, and was not elected. By 1940, she had moved to Oakland, and had given up teaching to work as the executive secretary of the Communist Party of Alameda County (C.P.A.C.). She became treasurer in 1944, finally leaving C.P.A.C. in 1945. She then went back to teaching.

In 1949, she mounted a dark horse campaign for the school board of Oakland. In her sworn statement as a candidate, she gave her reasons for running:

“My qualifications are: A former high school teacher and principal, university teaching assistant, and Unitarian minister, I have an A.B. and M.A. from University of California and studied at Manchester College, Oxford. I have resided thirty years in the Bay Area. My program is: Construct adequate school buildings, eliminating facilities now safe and unsanitary. Employ enough good teachers, adequately paid, to guarantee small, effective classes. Eliminate dissension. Hire more teachers from minority groups. Teach scientific facts answering misinformed race superiority ideas. Develop appreciation of contributions made by minority groups to American history and culture. Resist interference with academic freedom that stops scientific research and teaching. Prevent attacks against teachers’ rights as citizens by the ‘unAmericans.’ By electing me, a Communist, you are opposing the drive to outlaw the Communist Party which has historically been the first step toward fascism and the carnage of atomic war.”

Her campaign for a position on the Oakland school board caused consternation among the leadership of the A.U.A. Rev. Frank Ricker, the executive secretary of the Pacific Coast Unitarian Conference, sent an urgent telegram to Rev. Dan Huntington Fenn, saying in part:

“MRS LEILA THOMPSON RUNNING FOR OAKLAND SCHOOL BOARD AND IDENTIFYING HERSELF AS UNITARIAN MINISTER PLEASE WIRE TO CROMPTON FOR PUBLIC USE OFFICIAL DENIAL OF HER PROFESSIONAL CLAIM…”

Ricker followed up with a postal letter in which he quoted an anonymous source who supposedly said of Leila: “It is felt by some who knew her that she was not a success as a minister and was always ‘far to the left.’” Ricker was wrong to attribute the failure of her ministry solely to Leila, so this unsubstantiated remark merely reveals his hostility and prejudice.

In fact, what bothered Ricker was not the Leila’s professional competence, about which he knew nothing, but rather that she was both a Communist and a woman. This was at the beginning of the Communist witch-hunts led by Joseph McCarthy of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, and Ricker obviously did not want a Unitarian minister to be publicly connected with Communism. In addition, like so many Unitarians of his era, he was dismissive of any woman who claimed to be a minister. Ricker said in his letter to Fenn, “I am wondering if it would not be in good order for you, as Secretary of the Fellowship Committee, to write to the lady [sic], and point out that she has no right to use the professional designation.” Leila had not claimed to be a Unitarian minister in 1949, she merely made the truthful claim that she had been a Unitarian minister in the past. But the Unitarian men in power of the denomination at that time could not allow a woman to claim even that much.

Leila retired as a teacher in 1951, at age 63. In 1954, the House Committee on Un-American Activities listed her as as known Communist; she had been identified in testimony by four different people as a “Communist Party functionary.” One person’s testimony revealed that she had hosted a Marxist study session in her home in East Oakland. Fortunately for Leila, since she was already retired, this testimony didn’t threaten her job or income.

Unfortunately, little is known about what she did in retirement. She stayed in Oakland for the next fifteen years, and then in 1964 went back to live in Oregon. Her mother had died in 1950, and her father, Frank, was living alone, so she probably returned Oregon to be near him. Frank died that year, on November 6, 1964, at age 100. Leila herself died in Portland, Ore., on August 6, 1971, aged 82. The funeral service did not take place in the Unitarian church, but rather in the funeral home’s chapel; her obituary did however mention that she had been a Unitarian minister. She was buried in Corbett, Ore.

Conclusion

Leila’s intellect and character allowed her to rise out of rural poverty, and be recognized as an intellectual and a gifted Unitarian minister. This part of her story might serve as inspiration to us. But her story also reminds us how blind prejudice can waste human talent. When she entered into the Unitarian ministry, she was recognized as having great potential by denominational leaders both in Great Britain and in the United States. But officials of the American Unitarian Association had decided, through blind prejudice, that women should not be ministers, and their attitude forced Leila out of the ministry, back to teaching. This blind prejudice extended far beyond Leila to all women ministers, and remains a shameful episode in Unitarian history.

Then too, Unitarianism failed Leila by not claiming her teaching as a form of ministry — which could have brought credit to Unitarianism at no cost to the denomination — but she was forced out of fellowship as a minister simply because she didn’t work in a congregation. Finally, Unitarianism failed Leila during the anti-Communist hysteria of the McCarthy era. The American Unitarian Association could have quietly supported Leila’s freedom to believe in an unpopular political party, while still distancing itself from supporting Communism. Instead, denominational officials succumbed to the hysteria of the times, and repudiated her both publicly and privately. Leila Thompson was not well served by institutional Unitarianism. It is not surprising that her memorial service was held in a funeral chapel rather than in a Unitarian church.

Leila Thompson’s story should inspire us to confront the ongoing prejudice against women. Women still don’t have full equality today. Although more than half of all Unitarian Universalist ministers today are now women, the more prestigious and better compensated positions remain dominated by male ministers. In addition to confronting our own prejudices against women, perhaps Leila’s story will prompt us to confront others of our prejudices: Unitarian Universalist ministry is still overwhelmingly white and upper middle class. It behooves us not to waste the talents of people like Leila Thompson; there are enough problems facing us today that we need all the talent we can find.

Notes

1900, 1920, 1910, 1930 U.S. Census

Thompson, Leila Lashey [sic], Andover Harvard Theological Library, Unitarian Universalist Association Minister files, 1825-2010, bMS 1446/227

Passport application, Leila Lasley Thompson, Aug., 1922

Obituary, Portland Oregonian, Aug. 10, 1971

“Childhood Memories of Clara Lasley Salzman,” Clara Belle Lasley, Familysearch.org website ancestors.familysearch.org/L4WY-FQ5/clara-belle-lasley-1897-2004 accessed 21 October 2021

Polk’s Portland City Directory, 1907, 1910

Register, University of California, 1913-1914

Register — Fifty-second Commencement, May, 1915, University of California, 1915

Earl Morse Wilbur, Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry: The History of Its First Twenty-Five Years, Berkeley, Calif.: 1930

California Alumni Assoc., Directory of Graduates of the University of California, 1864-1916, Berkeley, 1916

Lincoln County Leader, Toledo, Oregon, June 2, 1916

Official Directory of … High Schools, State of Oregon, 1917-1918; 1918-1919

California Honor Role certificate for Charles Henry Thompson, Jr., Nov. 5, 1918

“Charles Thompson Dies on Battlefield in France,” Santa Rosa (Calif.) Republican, Nov. 6, 1918

Alfred S. Niles, “The Early Years of the Palo Alto Unitarian Society, 1947-1950,” mimeographed pamphlet, Palo Alto Unitarian Church, c. 1958

New York, N.Y., Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1957, S.S. President Harding, dep. France July 21, 1932, arr. N.Y. July 29, 1932

California Death Index, entry for Basha E. Thompson; “Incumbents in Berkeley Voting Win”

San Francisco Chronicle, March 5, 1937, p. 1

Obituary, Leula Auretta Lasley, Portland Oregonian, April 19, 1954

Obituary, Fred N. Lasley, Portland Oregonian, Nov. 6, 1964, p. 33

Annual Report of the Committee on Un-American Activities for the year 1953, Feb. 8, 1954, Washington, D.C., 1954

Oregon Death Index

Obituary, Portland Oregonian, Aug. 10, 1971, p. 9.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Susan Plass for contributing crucial research to this biography.