I’ve been using online shared spreadsheets (through Google Docs) as a congregational planning and scheduling tool for three years now. I thought I’d share some of what I’ve been doing, in hopes that others will share what they’ve been doing along these lines.

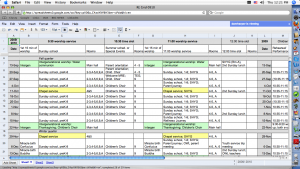

First, take a look at the Palo Alto churches “RE Grid 0910” (religious education planning grid for 2009-2010). This is an example of a moderately complicated planning grid using an online spreadsheet. Congregational planning in a mid-sized church like ours is focused on Sunday events, so moving up and down in the spreadsheet each row is designated with successive Sunday dates (the only exception is Christmas Eve, which gets its own row). Moving from left to right in the spreadsheet, we start off with columns for various Sunday morning time slots, and move into columns for specific programs (i.e., Children’s Choir, teacher training, youth programs, etc.). The religious education committee, the leaders of various programs, the church administrator, and I use this RE Grid for more efficient communication and coordination. From my point of view, what I like best is that other people can get answers to scheduling questions without having to ask me; furthermore, when we do planning, everyone is literally on the same (online) page which increases efficiency and reduces confusion.

Screen shot of RE Grid mentioned above

Next, here’s a worship planning grid from a small congregation. In this congregation, the musicians were very part-time, and usually could not meet with me with me to plan worship; I used the worship planning grid to share information about sermon topics, and they used the grid to share with each other the music they were playing so we didn’t get duplication. The lay worship associates used the grid to keep track of when they were scheduled. Staff and volunteers tend to be stretched thin in small congregations, and introducing this online spreadsheet as a planning tool made all our lives easier.

Two downsides to online documents for planning: (1) there’s a strong temptation to include too much information (no good solution for this); (2) there’s a tendency to delete old information without saving a copy for future reference (I export Excel versions of Google Docs spreadsheets for archives).

I’d love to hear how other congregations have used online shared documents for planning. Tell us what you’re doing in the comments, and give us a link if your online document is public.