Sermon copyright (c) 2019 Dan Harper. Delivered to the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, California.

When the Palo Alto Unitarian Society began began to meet in 1947, they didn’t own a building but met in rented space. After outgrowing other spaces, they finally wound up in the Palo Alto Community Center. Rae Bell, who joined the congregation in 1953, later recalled:

“It was a three ring circus on Sunday mornings! The number of children in the church school grew by leaps and bounds, and classes had to be held in adjacent homes, the YMCA, the Girl Scout House, the Junior Museum, and Harker School. The religious education teachers arrived each Sunday morning with all their supplies in one bulging box. An Arts Committee performed wonders with floral and art pieces to brighten up the dark Children’s Theatre where services were held. By 1955, a sixteen-voice adult choir squeezed into the miniature space to the side of the stage…. Given these crowded conditions, the impetus to build our own home was tremendous.” (1)

But how would they finance building their own home? As a new congregation, the American Unitarian Association in Boston still helped pay their minister’s salary. And where did they want their new building to be? Bob Harrison, one of the earliest members of the congregation, later remembered:

“We soon became solvent enough to plan with Boston for a church building. Some thought we should buy the old First Presbyterian building. I was chairman of the Board, and moderated a long meeting in the faculty clubhouse at Stanford on the pros and cons, and we finally decided to build [a new building]. We then looked for sites, including one on Loma Verde, but decided on the Charleston [Road] site.” (2)

A site at 1345 Channing Ave. was also considered (3), and it was even suggested they purchase the old Unitarian church building at the corner of Cowper and Channing. But even though some criticized the site on Charleston Rd. as just a cabbage field, others pointed out the advantages of being in an area where many new homes were being built.

The congregation voted on June 27, 1954, to buy the cabbage field, for which they paid $30,060 (about $285,000 in today’s dollars). They leased the field out for farming until they figured out what they wanted to build. They started off thinking small: in June, 1955, a group of people proposed building two modest buildings comprising 7,250 square feet at a total expenditure of $51,634 (approximately $500,000 in today’s dollars). (4) In November, 1955, Richard Allen and three others submitted a more considered proposal to the Board for buildings totaling of 8,280 square feet. The increased square footage was based on more careful calculations of the requirements for the Sunday school: “If three sessions [of church school] were scheduled each Sunday, six classrooms and one [children’s] assembly room would be sufficient for 540 children.” (5) Sunday school enrollment at that time was over 300 children, and rising rapidly.

The Board of Trustees also considered how the buildings would embody the values of the congregation. They wanted a building that would “reflect freedom of thought and action coupled with the disciplines of a mature mind,” a building that would “convey a tolerance for the religious beliefs of others, and recognition and retention of the good in cultures other than our own,” and that would “express a sense of human equality and brotherhood.” (6)

Once they had some sense of the building they wanted to build, the next step was to choose an architect. Bob Harrison remembered how they settled on Joseph Esherick:

“[Harrison’s wife] Rowena, Glen Taylor, and a few others were on the committee to select an architect from the many who submitted tentative plans. Rowena was particularly pleased with Esherick, who was later selected, because he seemed more sensitive to the feelings and interests of the entire congregation.” (7)

Esherick was the perfect choice for the congregation. Marc Treib, one of his graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley, and now emeritus professor there, has summed up Esherick’s architecture as always being “appropriate”: “[Esherick] wasn’t a major form-giver. He wasn’t a Frank Lloyd Wright. He didn’t do frivolous shapes — his architecture was quieter, and more about living and use, than flashy designs to be reproduced in the professional journals.” (8) In other words, instead of building a building that would show off his design prowess, Esherick listened attentively to his clients and built the building they wanted and needed.

Esherick may be considered a regional architect who carried on the regional architectural tradition of Julia Morgan and Bernard Maybeck. While our building is often categorized as Mid-century Modern, critic Lewis Mumford would have categorized it as “Bay Region Style, a mid-century follow-up to Maybeck and Morgan.” (9)

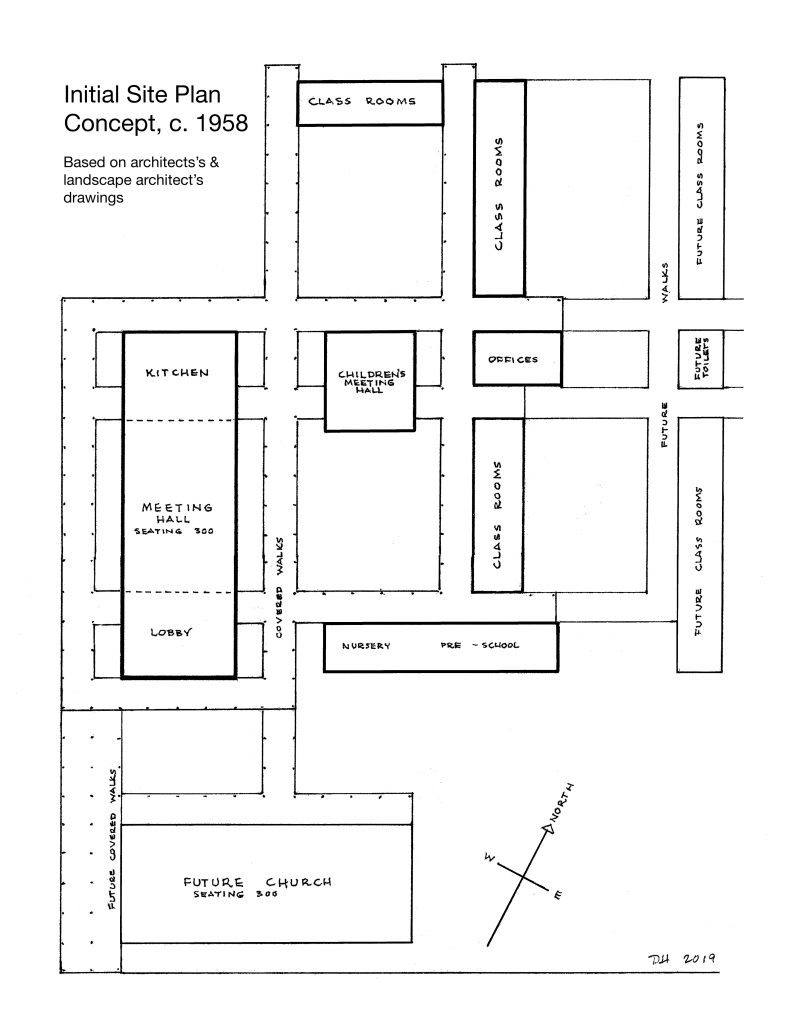

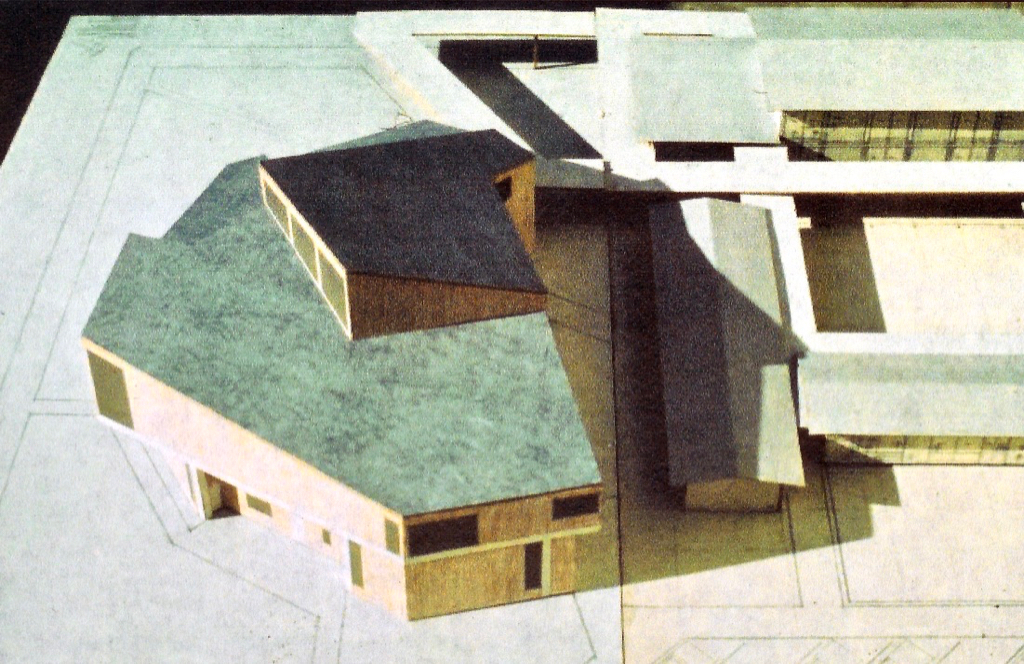

The vision that Esherick captured in our buildings is revealed in his original idea for the site plan, including plans for future classrooms and a future church building. His original idea shows our campus as a grid. This is in striking contrast to the typical Christian church, where there is a clearly defined path from the entry point to the altar or pulpit, just as there is a clearly defined path for Christians to the ultimate goal of salvation. A building complex based on a grid offers no neatly-defined path to salvation. Indeed, our campus continues to prove disorienting to first-time visitors; people regularly get lost on their first visit here because there is no single goal towards which our buildings aim us.

The grid came to be emblematic both of mid-century architecture, as well as some visual artists, such as the deeply spiritual painter Agnes Martin, whose paintings are based on a subtle, meditative grid. I believe there is a connection, too, to the freedom that was being explored by the jazz musicians of that era, as for example the spiritual jazz of Pharoah Sanders. Like free jazz, a grid suggests “limitless space and absence of place.” (11) A grid, then, is an excellent expression of the stated values of the congregation: freedom of thought and action, tolerance for the religious beliefs of others, and a sense of human equality.

In Esherick’s design, the grid extends from the large-scale site plan to the most sensitive and subtle details. The building elevations, now in the collection of the University of California at Berkeley, show how the facades of the buildings were organized into grids.

Then there are more subtle details: Esherick extended the rafter tails into space beyond roof lines, giving the feeling that the grid extends over those areas where there are no buildings. And the grid continues into the interiors of the buildings as well: long linear light fixtures hung from the ceiling of the classrooms extended a subtle grid above your head while providing soft and non-directional light.

Eshierck recognized the seriousness of purpose of the congregation, but he also understood that the congregation had a sense of humor, and there are witty touches throughout the buildings. In an oral history interview, Esherick remembered that the building “had to be very economical, but it has lots

of nice things in it…. One of the things I like most about it is that the lighting [in the Main Hall] is made up of great, big porcelain enamel reflector lamps, the kind of things that are used on a big, high shaft for parking lot lighting. I always look at that stuff and think of what it’s going to be like upside-down or right-side-up, and these are all used upside-down. They work wonderfully well. They give very good quality light.” (12) Although the wittiness of the bowl lights has been mostly forgotten today, members of the congregation who were involved in the building process always remembered what the bowl lights really were.

The building complex was constructed in six months for a total cost of $178,000 (about $1.6 million in today’s dollars) comprising 11,000 square feet. The first Sunday service was held on September 7, 1958. Rae Bell remembered “a massive all-day clean-up occurred on the previous day with wooden chairs uncrated… floors and windows washed, and rubbish removed.” (13) There was as yet no landscaping; photos of opening day show the patio outside the Main Hall was just bare dirt.

Religious education enrollment and adult attendance continued to rise, and soon the new buildings were filled past capacity. The adults met in the Main Hall, which held over 200 people on uncomfortable wooden chairs. (14) At each service, about one hundred children crammed into the Children’s Meeting Hall — what we now call the Fireside Room — before dispersing to their classrooms. In 1964, to alleviate cramped office space, the congregation built an extension, designed by Joseph Esherick, to the office building. (15) Attendance peaked in the mid-1960s, with three Sunday services, and as many as 600 children enrolled in Sunday school.

After a few years, Jobe and Jean Jenkins donated a madrone branch from their property in the Santa Cruz Mountains to be hung on the north wall of the Main Hall. (16) By deciding to hang this madrone branch on this wall, the congregation gave a firm and definite orientation to this room; now it felt more like a traditional Christian church, with an axial orientation towards the pulpit. This is one instance of the congregation resisting the radical openness of the grid; the uncertainty and openness of the grid plan was too uncomfortable.

By 1966 our congregation began to think about building a church building at the front of the lot. But the congregation has changed since 1958. Many people were no longer satisfied with the simple rectangular building shown on the original site plan. Deep divisions within the congregation became apparent as they tried to decide what kind of building they wanted.

Differing opinions about the war in Vietnam exemplify the divisions within the congregation. The senior minister, Dan Lion, and some congregants opposed the war; other congregants supported the war. In June, 1967, the church newsletter carried a letter from church member George Price, saying, “Our government is dedicated to PEACE. Peace in Vietnam is its primary goal there… I support my government.” Ed and Celia Freiburg responded in August, 1967, with the barbed criticism that “there are well-meaning members of our congregation who want us to assume the ‘white man’s burden’ abroad.” (17) In addition to open division over social issues, there was also hidden interpersonal conflict: lay leaders and the senior minister, Dan Lion, were increasingly in conflict. (18) Not surprisingly, then, there was also conflict around the proposed building project.

Joseph Esherick was retained to design the new building. In a letter to the Board president dated February, 1968, he quoted one of the stated desires of the congregation: for a building with the “speaker speaking from with in the community, an interdialogue; rather than a neutral setting or the traditional authoritarian setting.” To Esherick, that suggested a “radically different form” from the existing buildings, with a “face to face entrance with both congregation and minister coming essentially from the same side and, as it were, from the same place and meeting, confronting one another, in a single common space.” (19) The ideals represented by the grid — freedom, tolerance of other’s beliefs, human equality — were no longer at the forefront of people’s minds. What I hear instead is a desire to manage conflict; perhaps a new building could be a container for productive conflict, for what they called “inter-dialogue.”

George Price estimated the new building would cost 374,000 dollars (about $2.75 million in today’s dollars). (20) In an open letter, Arthur Coffman, a self-proclaimed member of the “Loyal Opposition,” argued: “At this time in the history of our nation and our church there are, to me, options with higher priorities than our own creature comforts at a cost of some $300,000.” (21) Assistant minister Mike Young tried to further the discussion by asking, “The new building, tough it will open up some new programming possibilities, will tend to commit us to become a ‘BIG’ church; with all that means in terms of potential resources, but also in terms of a diminished sense of being a community.” (22) But no congregational consensus emerged.

A congregational meeting was called in May, 1968, to affirm or reject the motion that: “It is the sense of the congregation that the Palo Alto Unitarian Church have a new auditorium. This building would be substantially like the one designed by Esherick and Associates.” One hundred of the congregation’s members voted no, while only sixty-six voted yes. Board president George Price called the majority “no” vote a “mandate to develop leadership in programs in the field of human rights.” The money raised during the capital campaign was then donated to various charitable organizations.

Why did the congregation make this decision? Unresolved conflict between the ministers and lay leaders helped prevent productive discussion, as did the conflicts between members of the congregation over Vietnam and other social issues. Additionally, based on comments made by those who were part of the congregation at that time, there were probably some who voted “no” because they thought the new design was ugly or inappropriate to the congregation. The consensus-building process that had been followed in 1958 was not possible in 1968.

The next half century of our building’s history will have to be the subject of another sermon. Instead, I’d like to reflect on how our building complex continues to make us feel uncomfortable.

Our congregation still feels tension between a desire for openness and a desire for some degree of certainty. It may make us uncomfortable knowing the madrone branch hangs exactly where a cross would hang in a traditional Christian church, but it makes us more uncomfortable to change the orientation of the Main Hall; when Amy and I experimented in 2009-2010 by orienting the chairs towards the west wall, many were disturbed and upset. We still prefer the certainty of knowing which direction we should face, and we still make small and large decisions to try to tame the radical openness of the grid.

Our discomfort with uncertainty means we do not find it easy to deal with opposing viewpoints. For one example, this congregation has less theological diversity than other Unitarian Universalist congregations I’ve been part of. We are dominated by atheists and humanists and non-theists; we have no pagan circle, no Christian fellowship, no Jewish roots group. For another example, we lack political diversity; everyone seems to belong to the Democratic party. Sometimes it seems to me this congregation clings to unexamined certainties embodied by atheism and the Democratic party the way some fundamentalist Christian churches cling to their King James Bibles.

Our desire for certainty conflicts with our visually stimulating and deeply unsettling buildings. The theological image that our building embodies for me is the image of the web of all existence, which includes all living organisms and all non-organic matter. (23) The web of existence has no center; we human beings are not the center, we are merely one node in the web. A subset of the web of existence is the web of all humanity, and privileged college-educated Americans are not at the center of all humanity; here again there is no center.

What happens if we de-center ourselves, recognizing our limitations as fallible, finite beings? We live in a world facing global environmental disaster, a world faced with mass movements of refugees. To live ethically, we must confront the reality that college-educated American human beings are not the center of the universe, and that humans are not the center of the web of existence.

In a Christian church, you know where God is: follow the straight-line path that begins at the front door and ends at the cross hanging on the far wall. Our building complex has no center, and that means God is either everywhere or nowhere; or rather is BOTH everywhere and nowhere; both atheism and theism are valid options for structuring human meaning. In our church, there is no one center, and thus on Sunday morning there will be many centers of activity: you can attend Sunday services, or participate in the Forum, or help prepare lunch in the kitchen, or be part of a class, or play on the playground, or join our bias-free Navigators scouting group in the covered patio. Each is a valid pathway towards spiritual growth and maturity.

However, I believe our congregation as a whole — not referring to specific individuals, but the congregation as a whole — still lacks the spiritual maturity to fully embrace the implications of our building complex. We resist uncertainty. We resist being de-centered. We cling to our self-importance because we are steeped in the hyper-individualism of our consumerist information-driven society. We still believe freedom means “I get to believe and do whatever I want.”

Our building complex confronts us with a higher ideal: we are not isolated individuals who can believe whatever we want, we are part of the web of all existence. Our building complex tends to shape us towards growth in spiritual maturity, so we stop pretending that we are the center of the universe, we stop demanding certainty. Will we allow ourselves to be so shaped?

Notes:

(1) Rae Bell, “A History of Unitarians in Palo Alto, Part II,” Winter, 2003, issue of “Mosaic” (Palo Alto: UUCPA, 2003).

(2) Robert Harrison, Typescript in the UUCPA archives, handwritten title “Bob Harrison: Memories, Aug. 7, 1983.”

(3) Coincidentally, this site is adjacent to Eleanor Pardee Park; Pardee was a prominent member of the early Unitarian Church of Palo Alto that existed from 1905-1934.

(4) Don Borthwick et al. (65 other co-signers), “A practical plan for developing our Charleston Road property NOW,” presented at the June 20, 1955, Board meeting. The proposal called for a 4,000 square foot Sunday school building and a 3,250 square foot social hall that would also hold Sunday services.

(5) Richard Allen, Donald Borthwick, Mrs. Robert Kenyon, Jospeh O. Whitely, Jr., “Report of Subcommittee II, Building Space Requirements, Richard Allen, Chairman,” submitted Jan. 8, 1956.

(6) “Architectural Objectives,” Jan., 1956, typescript in the UUCPA archives.

(7) Robert Harrison, 1983.

(8) Quoted in Carol Ness, “A Bay Region master: The architecture of Joseph Esherick finally gets its due,” UC Berkeley News, November 5, 2008, www.berkeley.edu/news/berkeleyan/2008/11/05_esherick.shtml , accessed 20 June 2019. Treib’s book about Esherick’s work is titled “Appropriate.”

(9) Ness, 2008. Esherick studied with one of Bernard Maybeck’s proteges, William Wurster; the earlier Unitarian church in Palo Alto had been designed by Maybeck; thus our present building has stylistic links to that earlier Unitarian church.

(10) This analysis is based on Thomas Barrie’s idea of the “grid path” in his Spiritual Path, Sacred Place: Myth, Ritual, and Meaning in Architecture, Boston: Shambala, 1996, pp. 116-118.

(11) Barrie, p. 118.

(12) Joseph Esherick, “An Architectural Practice in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1938-1996,” 1996, an oral history conducted in 1994-1996 by Suzanne B. Riess, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1996.

(13) Rae Bell, 2003.

(14) That the chairs were uncomfortable was reported by several early members of the congregation.

(15) Total cost for the addition was $5000 (about $40,000 in today’s dollars); letter in the UUCPA archives dated February 13, 1964, from J. A. Aplin, Trustee Member for Building, to Hans Stern, building contractor. This addition includes the present-day library.

(16) Typescript in the UUCPA archives, “Facts about the old madrone branch, from jean Jenkins, as told to April Hill,” n.d. This typescript states that the first madrone branch was placed on the wall in 1962; however, photographs of the Main hall interior that apparently date from before this time also show some kind of branch mounted on the wall.

(17) Clippings from the church newsletter in the UUCPA archives.

(18) For documentary evidence of this conflict, see for example, Ron Hargis, “The Palo Alto Unitarian Church: An Analysis,” 2 pp. typescript dated January, 1977.

(19) Letter from Joseph Esherick to Dr. Jobe Jenkins, dated February 6, 1968; typescript in the UUCPA archives.

(20) Typescript in UUCPA archives, “PAUC New Building Costs,” signed G. W. Price, and dated April 20, 1968.

(21) Arthur Coffman, typescript titled “A New Building?: Thoughts from a Member of the Loyal Opposition,” n.d. (1968).

(22) Mike Young, typescript in the UUCPA archives titled “An Open Letter from the Assistant Minister,” April 19, 1968. Sid Peterman, the interim senior minister following Dan Lion’s resignation, wrote in his final report to the congregation that the church at that time was a large church that was run like a small church; Mike Young’s resistance to becoming a “BIG” church becomes more understandable in light of Peterman’s analysis.

(23) My understanding of the web of existence comes, not from the “Seven Principles” of the Unitarian Universalist Association, but from theologian Bernard Loomer. See e.g. his “Unfoldings,” Berkeley, Calif: Unitarian Universalist Church of Berkeley, 1985.